![]()

Introduction

Intended learning outcomes

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Appreciate environmental issues as a crisis of governance.

- Define the features of governance.

- Identify the main challenges and opportunities for environmental governance.

- Understand the structure and scope of this book.

Voltaire’s Snowflake

No snowflake in an avalanche ever feels responsible.

(Voltaire, 1694–1778)

Like Voltaire’s snowflakes in the avalanche, environmental problems are everyone’s fault but nobody’s problem. Walt Kelly summed the dilemma up famously on a poster he designed for Earth Day in 1970, saying “We have met the enemy and he is us.” This chapter outlines how governance can help address environmental problems, by securing collective action between the diverse groups that make society up, such as businesses, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), government organizations and the public.

The chapter begins by discussing environmental issues as a crisis of governance, or a failure to organize our societies and economies in such a way that they do not harm the environment. As the process of steering and enabling collective action, governance has a key role to play in re-organizing society. The chapter then moves on to discuss the implications of uncertainty for those charged with governing the environment, and the opportunities that it presents for change. While the challenges to coordinating action are considerable, there are numerous successful examples from which inspiration can be drawn.

The final section outlines the structure and scope of the book, commenting on its approach, giving an overview of each chapter, and explaining the various boxes and learning tools that are included.

The Environment As a Crisis of Governance

Mike Hulme (2009: 310), a lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Third Assessment Report in 2001, recently claimed that climate change is a “crisis of governance … [not] a crisis of the environment or a failure of the market.” Established in 1988, the IPCC gathered vast amounts of evidence to first detect whether the climate was warming, and second to decide whether the warming was attributable to the polluting activities of humans. Following the publication of its fourth assessment in 2007, it is now widely accepted that the answer to both these question is a resounding “yes”—the global climate is warming, and we are to blame.

While the range of scenarios for warming differ in their exact timings, all strongly suggest that a major environmental crisis will occur sometime before the end of the twenty-first century if we continue along our current trajectory of economic development. In other words, “business as usual” will lead us over the edge. The acquiescence of the US administration to enter climate change negotiations in 2009 indicates that this scientific assessment is now widely accepted. How, then, to explain the failure of Copenhagen to secure a binding agreement on emissions reduction? Put another way, if accepted science predicts a forthcoming crisis, then why do we seem unable to act (Zizek 2008)?

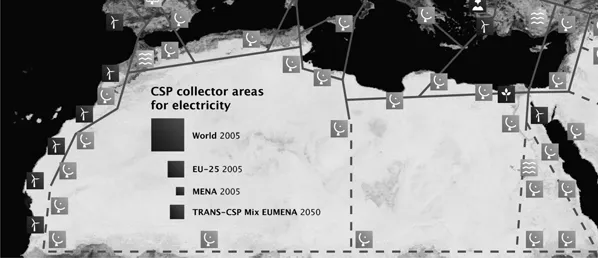

A common suggestion is that we do not possess the necessary technology to address the causes of climate change. But a plethora of solutions for polluting industries already exist, ranging from electric cars and wind power through to biodegradable crisp bags and carbon positive housing. The Desertec Foundation, an NGO formed to promote the generation of solar power in deserts, estimates that covering approximately 300 square km of the world’s deserts with solar panels would produce enough power to supply current global energy needs. Plate 1.1 shows the area of the Northern Sahara required to supply the energy requirements of the world, Europe, and the Middle East nations respectively. The potential is enormous. Why, then, are such technologies not being adopted?

Plate 1.1 Area of desert required to supply global energy needs

Source: reproduced with permission from Desertec Foundation, www.desertec.org.

Perhaps the answer is economic. Alternative technologies are notoriously expensive to install and run—certainly more expensive than their existing counterparts. Again, though, this argument falters. Governments around the world subsidize polluting industries such as oil, industrialized agriculture and car manufacturing to the tune of at least 2 trillion dollars every year. These so-called “perverse” subsidies actually work against many stated political priorities. So, for example, subsidizing the price of gasoline prolongs the dependence of the US on foreign suppliers, discourages the development of clean technologies, contributes to traffic congestion (which costs an estimated $100 billion per year), increases carbon emissions and decreases air quality (Myers and Kent 2001). Further, as the 2008 financial crisis showed, there is no shortage of money available to address an emergency that is perceived as urgent.

The answer to these apparent paradoxes is that climate change is no longer primarily a scientific or technological challenge, but a political, social and economic one. The greatest obstacle to mounting solar arrays in Northern Africa is the reluctance of Europe to cooperate with African countries for power. The greatest barrier to implementing new technologies is that we are economically and socially locked-in to the ones that we already have. Steering development onto a different course requires political vision to change engrained beliefs and habits. Lipschutz summarizes the problem neatly when he says, “rather than seeing environmental change as solely a biogeophysical phenomenon … we should also think of it as a social phenomenon” (1996: 4, emphasis in original).

Defining Governance

As the study of how to steer the relations between society and the environment, environmental governance is central to this task. While there is no single school of thought about what governance is, it is generally taken to mean “the purposeful effort to steer, control or manage sectors or facets of society” in certain directions (Kooiman 1993: 2). As Kemp et al. (2005: 26) state in relation to the environment, “we cannot assume the wisdom of the market, or any other blind mechanism. Nor can we conjure up the commitment and omniscience required for comprehensively capable central authority. In the establishment of effective governance for sustainability, we must incorporate and also reach beyond the powers of commerce and command—a task best accomplished through understanding, guidance and process.” Governance provides a third way between the two poles of market and state, incorporating both into a broader process of steering in order to achieve common goals.

Governance extends the practice of governing to non-state actors, or stakeholders, who have an interest or “stake” in governing, including charities, NGOs, businesses, and the public. Broadening the act of governing in this way brings more resources to bear upon policy problems and maximizes support for decisions. The vast majority of theorists agree that “the role of government in the process of governance is much more contingent” now than before (Pierre and Stoker 2002: 29), shifting from one of rowing to one of steering (Rhodes 1997). While traditional government by the state is a form of governing (Bulkeley and Kern 2006), this book focuses specifically on governance that involves non-state actors (but that may still include the state).

Governance operates by setting common goals or targets, which allow different actors to devise the most suitable ways to reach them. Accordingly, many aspects of governing have been devolved to networks of non-state actors, and new forms of governing have proliferated. Governance is seen by some as the only way to govern an increasingly unruly world, in which the old economic and political coordinates have been eroded by the forces of globalization (Herod et al. 1998). To others, the turn to governance undermines the political sphere, replacing democracy with an empty form of proceduralism (Lowndes 2001). This debate extends into the environmental field, and is returned to throughout the book.

The concept of governance emerged from different historical and intellectual lineages, and is used to describe shifts across a number of related but different areas, leading to a degree of confusion concerning the term’s usage. In his review, Kooiman (1999) identifies ten different usages of the word:

Governance as the minimal state where governance becomes a term for reducing the extent and form of public intervention, relating to the hollowing out of the state under neoliberalism.

Corporate governance which refers to the way big organizations are directed and controlled, rather than run on a day-to-day basis.

Governance as new public management describing the infiltration of corporate techniques of management and institutional economics into the public sector.

Good governance as a checklist approach to transparent and accountable governing advocated by the World Bank.

Socio-cybernetic governance whereby decisions require the input of multiple actors, all with different knowledges and competencies.

Governance as self-organizing networks in which the state is just one among many actors involved in governing.

Governance as steering as found in the German and Dutch emphasis on the role of governments in steering, controlling and guiding different sectors.

Governance as an emerging international order used by international relations scholars to describe a system of global governance.

Economic governance which focuses specifically on governing the economy or economic sectors.

Governance and governmentality which draws on the French scholar Michel Foucault’s analysis of the modern state.

To which could be added:

Governance as a form of democratic pluralism which extends the involvement of the public in decision-making (Kemp et al. 2005).

Many of these definitions are returned to and discussed in depth throughout the book. Despite the multitude of contexts in which the word governance is used, and the number of debates surrounding the concept, it captures a very real shift towards more collective approaches to governing societies (Kersbergen and Waarden 2004). A review of the literature finds a good deal of agreement around three core principles of governance: a commitment to collective action to enhance legitimacy and effectiveness, a recognition of the importance of rules to guide interaction, and acknowledgement that new ways of doing things are required that go beyond the state (Kooiman 1999, 2000).

Various modes of governance exist, which facilitate collective action in different ways. Network governance involves voluntary partnerships between diverse stakeholders to build consensus and the collective will and ability to act around a specific issue, while market governance uses financial tools and incentives to steer collective action. Rather than focusing on the specific tools or techniques that are used to address environmental issues, this book focuses on how modes of governance generate different types of collective action and outcomes.

As the practice of governing through cooperation in the absence of a centralized state or dictatorial power, governance has obvious use in addressing environmental problems, which are often global in scope and require a vast range of different people to act collectively. The next two sections outline the challenges of collective action and the opportunities for change presented by environmental issues.

The Challenge of Collective Action

Five key challenges to collective action can be identified in the environmental field. First, scientific uncertainty can make policy-makers hesitant to act. Second, the subjective nature of environmental problems means that solutions can never be right, but merely more or less acceptable to different groups. Third, many environmental problems are transboundary in character, which means that they require international cooperation. Fourth, and closely related to this, the current system of nation states tends to breed competition rather than cooperation. Finally, environmental issues tend to have complex causes that spill across many different areas of human activity, making it hard to coordinate action. It is worth briefly unpacking each of these challenges.

Within the traditional linear model of policy-making, scientists first get the facts right, then decision-makers decide what to do based on these facts (Davoudi 2006, Jasanoff and Wynne 1998). This model appeals to policy-makers because it suggests that there is an objective reality upon which rational decisions can be based. Environmental issues rarely work like this though, because they are characterized by high levels of uncertainty.

Two examples, one simple, and one complex, illustrate the difficulties of establishing scientific facts about the environment. The measurement of a coastline would appear to be fairly straightforward, and yet the answer depends entirely on the scale at which it is measured. Measuring the coast of Canada from geostationary satellite imagery taken from 36,000 km above the earth will overlook smaller inlets. Using accurate maps will produce a larger figure. And if a surveyor walked the entire coast, measuring around every pebble and rock at a certain point in the tidal range, they would conclude that the coast of Canada is infinitely long. Of course, the coastline of Canada does not change length in reality, but the reality we know depends on subjective choices, like how we chose to measure it.

The problem escalates when scientists attempt to understand highly complex systems such as the atmospheric–oceanic system that controls global climate. The fundamental problem is that the climate system has a degree of ontological uncertainty built into it. Ontological uncertainty concerns the actual reality of its functioning, rather than deficiencies in our understanding of it, and no amount of improvement in knowledge or computing power will help. Atmospheric physicists still lack any convincing model of how clouds exchange energy, making attempts to scale up to the entire atmosphere highly problematic (Shackley et al. 1998). While the global climate is precisely the system about which politicians want certain knowledge, it is also one of the most chaotic and unpredictable.

But even if scientists could determine the exact adverse environmental effects that might accompany different atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide, they cannot say whether the impact, or risk of the impact, is tolerable. So, for example, if the world continues along a “business as usual” trajectory, then the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases is predicted to treble by the end of the century. This gives at least a 50 percent chance that global average temperature increases will exceed 5°C. The general consensus is that extremely bad things like complete ecosystem collapse will happen past 5°C, but again, these are only probabilities (IPCC 2007). This has led scientists to advocate the adoption of a 2°C guardrail, addressed in Key debate 1.1. Ultimately, though, the question of what level of risk is tolerable, and what is “acceptable” in terms of cost and damage, is a political question and the answer will vary depending on who is being asked.

In the absence of scientific certainties, the definition of environmental problems and their solutions will vary according to whose perspective it is seen from, posing what policy analysts call a “wicked problem” (Rittel and Webber 1973). This leaves decision-makers in the unenviable position that their policies can never be right or wrong, but merely more or less acceptable to different groups of people. Climate change certainly seems to belong to this category of problems—people can’t even agree whether it is a problem, let alone how to solve it (Auld et al. 2007, Levin et al. for...