![]()

Part I

Creating a university of the air

![]()

1

The challenge of The Open University

The impact of The Open University (OU) has been enormous. It is available in many countries, has been reworked for many more and provides inspiration for a rich diversity of learners on their individual journeys. Through initiatives such as the National Open College Network some of its most successful ideas have been have spread across the UK.1 It is widely admired. Prime Minister David Cameron called it ‘a Great British innovation and invention’.2 Others have noted its integration within the wider society. Bill Bryson rhetorically enquired ‘What other nation in the world could have given us William Shakespeare, pork pies, Christopher Wren, Windsor Great Park, The Open University, Gardeners’ Question Time and the chocolate digestive biscuit?’3 However, the OU has become more than a much-emulated ‘national treasure’.4 Since its foundation in 1969 it has transformed the lives of the millions who have studied through it and challenged the very idea of a university. In the face of disdain and disbelief this unique institution has had impacts far beyond the higher education sector. It has drawn on the traditions of part-time education for adults, developed from the eighteenth century, on correspondence courses, associated with the rapid industrialisation of the nineteenth century and on university extension initiatives, which started in the 1870s. It has also developed ideas derived from sandwich courses, summer schools, radio and television broadcasts, for which there were precedents in the twentieth century. It owes much to its supporters, particularly its vast student body. Through its enthusiasm for learning and positive societal change the OU has affected the lives of people around the world, including those who, while not formally registered as students, acquired materials or watched broadcasts. This book examines its impacts by considering its structures, precedents, politics, pedagogies and personalities.

In defiance of the warning, attributed to Aristotle, that ‘there are two human inventions which may be considered more difficult than any others – the art of government and the art of education’, many of the key events in the creation of the OU occurred through swift government action between 1963 and 1969.5 Having noted down his ideas for a ‘University of the Air’ on 14 April 1963, Harold Wilson, the Leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition since 14 February 1963, proposed to a Labour Party rally on 8 September 1963 that which he later admitted was an ‘inchoate idea’ (Figure 1.1).6 It was for ‘the creation of a new educational trust’.7 This ‘University of the Air’ would be provided with broadcasting time and government assistance.8 Wilson swiftly and successfully embedded his uncosted and unproven proposal for a ‘University of the Air’ as soon as he came into the office of Prime Minister (PM) in October 1964. The new PM gave a trusted ally, Jennie Lee, the task of producing a White Paper on the subject before the next election, which was likely to be soon, as Labour’s parliamentary majority was tiny. The White Paper was published and an election pledge was made to create a ‘University of the Air’. In 1966 Labour was returned with an increased majority, and work on the promised new university began. Drawing on the legal assistance of Lord Goodman, the support of some well-versed civil servants (including some within the Department of Education and Science – DES) and the use of some ad hoc arrangements (notably the creation of Advisory and Planning Committees outside the DES), Jennie Lee shaped Wilson’s idea into a practical proposition. In 1969, shortly before the 1970 general election that Labour lost, The Open University was granted a Royal Charter, and by January 1971 the first OU students had received their mailings and watched the first television broadcasts.

Figure 1.1 When Wilson proposed a university of the air in September 1963 the idea received a lot of coverage. The Daily Mail’s cartoon featured Wilson as the television host of an ‘educational parlour game’ called ‘Double Your Diplomas’. A Daily Mirror cartoon portrayed the Conservatives as dismissive and envious, and the Sunday Citizen (a tabloid owned by the Co-Operative Press) also made a party-political point. When he opened the OU in 1969 Geoffrey Crowther acknowledged its role as an ‘educational rescue mission’, and in the Citizen Glan Williams showed Boyle’s wooden vessel (Edward Boyle was Conservative Minister of Education 1962–64) as having sunk, leaving Wilson to rescue the poorly educated.

Foundation

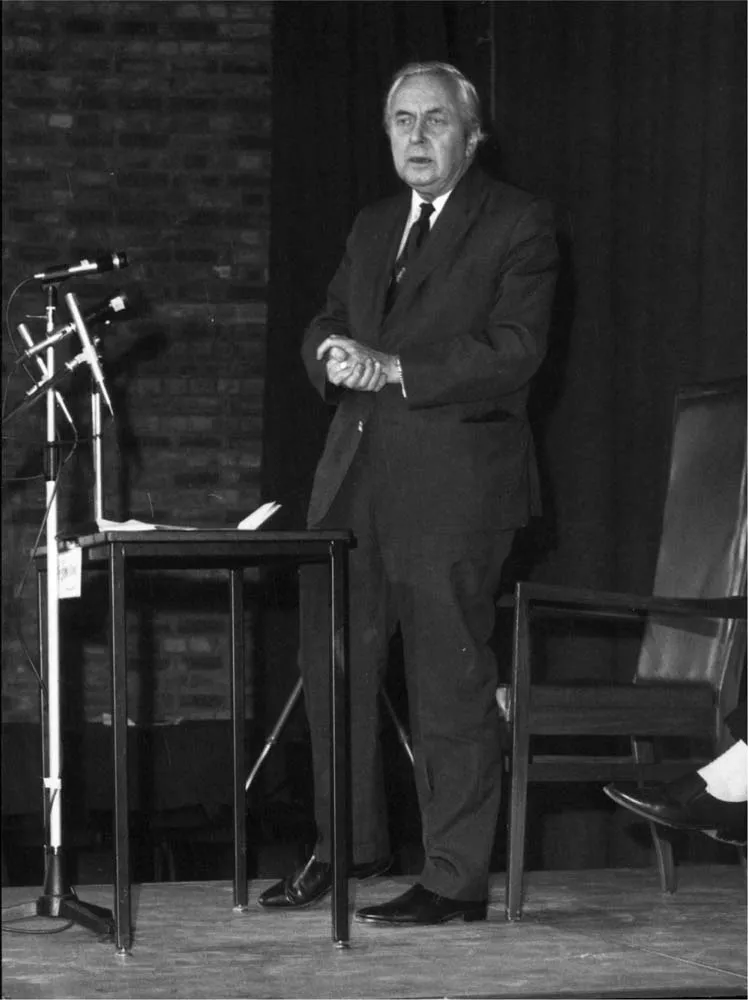

In Part I the focus is on the handful of innovators who ‘were crucial’ for the creation of the OU, which enjoyed a ‘rapid gestation period’.9 Phyllis Hall referred to the impact of ‘a few powerful individuals’.10 Harold Wilson, when recalling 1963, stressed the role of individuals (Figure 1.2):

It certainly wasn’t official Labour Party policy at this stage, except in the sense that I was running the party in a slightly dictatorial way; if I said something was going to happen, I intended it to happen.11

This was a feature of the OU that found echoes elsewhere. Dodd and Rumble noted that the ‘personal commitment’ of a minister was a feature common to the creation of a number of distance-teaching universities.12

While individuals were of importance, the OU was built on more than strong personalities. It is also in Part I that the wider social and political framework is considered. During 1963, the year of Wilson’s announcement, ideas about rights, about the Cold War and about higher education gained wider salience. This was in part due to the coverage given to the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (in February), to Kennedy’s ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech in West Germany (in June), to Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech in Washington (in August) and to the opening of another new university, the University of East Anglia (in September). While there were countervailing tendencies, the notion gained traction that a university could be committed to teamwork and discussion, widening access to power, promoting cross-class engagement in civil society and enabling the systematic facilitation of social and economic mobility. The OU’s values were reflected in its Charter, which was based on that of the University of Warwick, opened in 1965. In its emphasis on openness, the OU echoed the motto of another new university, Lancaster (opened 1964): Patet omnibus veritas (Truth lies open to all). However, unlike other universities, it had a commitment to the ‘educational well-being of the community’.13

Figure 1.2 Harold Wilson addresses The Open University.

Wilson was also able to build on existing ideas within and around his party. In 1945 Ellen Wilkinson, the Minister of Education 1945–47, proposed the broadcast of lectures.14 In 1960 Professor George Catlin, a member of the National Broadcasting Development Committee, called for a television university based not on the BBC, which had rejected his ideas, but on a new third channel. Woodrow Wyatt introduced a bill to the Commons in 1961 to facilitate the expansion of adult educational broadcasts, and the Pilkington Committee on the future of broadcasting, which reported in June 1962, assessed educational broadcasting.15 In March 1962 Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour Party leader, established a Labour Party study group, chaired by Lord Taylor, to consider higher education. Its report, with a foreword by Harold Wilson, called for a ‘University of the Air’.16 The interest of the left was noted. In 1966 the Times Educational Supplement described the OU as a ‘cosy scheme that shows the Socialists at their most endearing but impractical worst’.17 Sociology professor Norman Birnbaum, who taught in both the US and UK, recalled that ‘when I visited Milton Keynes in 1972, I was struck by the utter familiarity of the rhetoric of the Open University’. He went on to argue that it was not simply a ‘secularised version of socialism’ but also an ‘appeal to prescient technocrats unburdened by socialist aspirations’ and ‘an answer … to the problem of rising educational costs’.18

The values which framed the institution, the recognition of the benefits of pluralism, dissent, equity and the belief that humans can and should shape the world have often been associated with social democracy. When Michael Young (who worked for Labour and later became a Social Democratic Party peer) argued that ‘the tap-root of socialism was in working-class communities [where] the poor were helping the poor’ he provided an image of altruism expressed in the form of reciprocity which informed the thinking behind many of the schemes to which he contributed, including the OU.19 A number of those who had some responsibility for the foundation and design of the OU had similar political perspectives. Walter Perry (the first Vice-Chancellor) was twice Social Democratic Party deputy leader in the Lords, and, as OU Professor Stuart Hall noted, the OU was ‘filled with good social democrats. Everybody there believes in the redistribution of educational opportunities and seeks to remedy the exclusiveness of British education.’20 He later pointed out ‘it would have been funny to come to the OU and not to be committed to redistributing educational opportunities’.21 The university certainly attracted some staff with left-wing views. Arnold Kettle was a member of the Executive Committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain, David Potter had been fired from his previous university because of his association with the left and Aaron Scharf, the first Professor of Art History at the OU, only came to England after he was victimised by Senator McCarthy and accepted an invitation from a fellow art historian, the spy Anthony Blunt. Others at the OU noted that there was wide support among staff for the bolstering of social democracy through the utilisation of modern centralised systems of production and distribution.22 Many at the OU sought not to reproduce the privileges and dominance of the ruling class or to justify inequitable access on grounds of merit. The OU had its left-wing critics, who saw it as a ‘pale reflection of the conventional class-ridden establishments’. It had been ‘perhaps overeager to win the acceptance of the rest of academic society’. Nevertheless, it remained a ‘great liberal experiment’.23 It was, to quote its Planning Committee, firmly located within the British tradition of ‘being liberal expansionist in tone, empirical and specific as to numbers and money’.24

Wilson presented his idea about a ‘University of the Air’ to the 1963 Labour Party conference within the context of a speech about ‘Labour’s plan for science’.25 In this, he argued that social progress and peaceful developments could be achieved by investment in research, particularly in science and technology. It was, Tony Benn recalled, an ‘industrial speech’ which broke away from the ‘romantic attitude’ of the Tories.26 Wilson proclaimed:

The Britain that is going to be forged in the white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive practices or for outdated methods on either side of industry. We shall need a totally new attitude.

The University of the Air was going to contribute to the cultural life of the nation and also provide more scientists and technologists. This was a period in which scientific intellectuals with technocratic expertise and an enthusiasm for rational planning were gaining higher status.27 Norman MacKenzie, founder of the Centre for Educational Technology at the University of Sussex, sat on the Advisory Committee (which wrote the 1966 White Paper on the ‘University of the Air’) while representatives from the Ministry of Technology attended committee meetings. The expansion of higher education, the restructuring of the science policy machinery and the 1968 report on the civil service by Lord Fulton led to a technocratic zenith during the 1960s.28 The 1964–70 Labour government substantially increased spending on higher education and scientific research, much of it carried out in universities. The graduation rate for scientists and engineers rose higher than that of many other countries.29 During a surge in economic activity in North America and Western Euro...