eBook - ePub

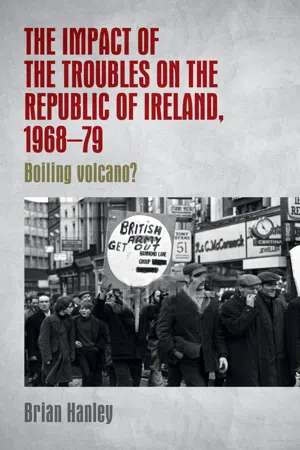

The impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968–79

Boiling volcano?

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The first book to examine in detail the impact of the Northern Irish Troubles on southern Irish society. This study vividly illustrates how life in the Irish Republic was affected by the conflict north of the border and how people responded to the events there. It documents popular mobilization in support of northern nationalists, the reaction to Bloody Sunday, the experience of refugees and the popular cultural debates the conflict provoked. For the first time the human cost of violence is outlined, as are the battles waged by successive governments against the IRA. Focusing on debates at popular level rather than among elites, the book illustrates how the Troubles divided southern opinion and produced long-lasting fissures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968–79 by Brian Hanley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘Something deep was stirring’

Missiles, including petrol bombs, rained down on the British Embassy as protesters tried to force their way past Garda lines. But it was the crowd who were driven back and away from Merrion Square, some of them breaking windows in the Shelbourne Hotel as they went.1 The violence took place on the night of Saturday 12 October 1968 and was the third such Dublin protest in the week following the batoning of civil rights marchers in Derry on 5 October.2 The marchers had come from a rally at College Green, where 500 people had listened to republican and socialist speakers, including Eamonn McCann and Seamus Costello. Costello's party, Sinn Féin, had held their own meeting earlier in the week, and republicans had also organized a 600-strong march in Cork city.3 A Labour party meeting, at which Belfast MP Gerry Fitt had given an emotional account of the Derry events, attracted the largest crowd of about 1,000. Fitt warned the Unionist government that if future protests were suppressed ‘the people of Dublin, young men and women, will cross over the Border’. Dublin's Labour Lord Mayor Frank Cluskey promised ‘the people of the North’ that their ‘days of abandonment are very near an end’.4

The focus for many protests over the next three years would be the Embassy at 39 Merrion Square, a four-storey building with the British Passport office located just a few doors away at No. 30. Securing it ‘was always a head-ache as far as Gardai were concerned’ as the public could walk up just five steps to the Embassy front door, which despite double-glazed windows with reinforced shutters was quite vulnerable, as future protests would show.5

‘Rough and ruthless men’

The violence in Derry on 5 October, broadcast that evening on RTE news, dominated headlines in the Republic. Visiting the Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Jack Lynch that week, Nationalist Party leader Eddie McAteer MP had called on the citizens of the ‘deep south’ to show their support for the people of Derry.6 Several county councils passed motions pledging solidarity with northern nationalists.7 The opposition Fine Gael party, ‘shocked at the violence against a peaceful demonstration’, sent its two Donegal TDs to Derry to gather first-hand accounts.8 Derry had focused attention on civil rights just as the Republic was preoccupied with an attempt by the government to replace the proportional representation (PR) voting system. A referendum to endorse that change was due to take place on 16 October. Critics noted that without PR, Fianna Fáil would be guaranteed electoral dominance. Campaigners also stressed that the introduction of PR was one of the demands of civil rights protesters in the North. Labour's Barry Desmond asserted that ‘if P.R. is abolished … the cities of our Republic will be carved up in the same manner as the notorious ward system of Derry’. Tom O’Higgins of Fine Gael compared Fianna Fáil to the Ulster Unionist party, both run by ‘rough and ruthless men … determined to maintain themselves in office for as long as possible’.9 Embarrassingly, the government was humiliated in the referendum.10 To make matters worse, their republican credentials were also called into question. Lynch's administration had followed that of Sean Lemass in seeking cooperation with the Northern government.11

Now, Labour leader Brendan Corish alleged that the government's failure to defend nationalists revealed as ‘fiction’ the ‘Fianna Fáil claim that they in some way represent the Republican tradition’. Patrick Lindsay of Fine Gael asked ‘what has the Fianna Fáil Party done about partition since 1932? Nothing.’ Labour TD Michael Mullen, a senior figure in the Irish Transport and Workers Union, complained that ‘we seem to have stalled in this part of Ireland on the important matter of abolishing partition’.12 Soon, leading Fianna Fáil figures, such as Neil Blaney and Kevin Boland, began to take a more militantly anti-partitionist line.13 In Letterkenny during November, Blaney reiterated the ‘right of the Irish people in their homeland to be united and free’ a message that evidently struck a chord with many Fianna Fáil activists.14

‘The struggle is the same’

For radicals, the referendum result and the growing crisis in the North seemed to confirm the belief of Irish Times political correspondent Michael McInerney that ‘something deep was stirring in the whole of Ireland’.15 At Sinn Féin's Ard Fheis in December, party president Tomas Mac Giolla claimed that the ‘slumbering and despairing Irish nation has suddenly awakened’ and was ‘witnessing what we hope is the beginning of the disintegration of two old and corrupt parties in Belfast and Dublin’.16 Activists would continue to liken Fianna Fáil's administration to that at Stormont. In January 1969, Labour's Noel Browne compared a new Criminal Justice Bill to Northern Ireland's Special Powers legislation.17 His colleague, Conor Cruise O’Brien, described the same bill as an ‘encouragement to the Unionist Party in its continuing denial of civil rights in the Six Counties’.18 As housing protesters took to the streets of Dublin, their counterparts occupying Derry's Guildhall asserted that ‘the struggle is the same: North and South’. Civil rights committees sprang up concerned with th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- A note on government, society and terminology

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Something deep was stirring’

- 2 ‘The nation on the march’

- 3 ‘It’s all going to start down here’

- 4 Offences against the state, 1970–72

- 5 ‘Are we trying to create a new Chile here?’

- 6 Refugees and runners

- 7 ‘The other minority’

- 8 ‘But then they started all this killing’

- 9 ‘They want to tell lies about our history’

- 10 ‘Practically a foreign country’?

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index