![]()

PART ONE

GEORGIA:

General Background

![]()

Georgians at Home

THE AVERAGE Georgian votes the Democratic ticket, attends the Baptist or Methodist church, goes home to midday dinner, relies greatly on high cotton prices, and is so good a family man that he flings wide his doors to even the most distant of his wife’s cousins’ cousins. But these facts, significant as they are, should not be taken as all-revealing. In this, the largest of the southeastern states, there is no one characteristic type, even though the racial texture is relatively simple. The lethargic Georgia cracker of popular legend, with his drawl, his tattered overalls, and his corncob pipe, is no more typical than several other figures. The term “cracker,” which originated in connection with the cracking whips of the early tobacco rollers, has evolved into a term of double meaning. Since it may designate any Georgia citizen or the most slovenly of the poor-white class, the visitor would be wiser not to thank his hostess for her delightful cracker hospitality.

Even in politics it is unsafe to make predictions. The average Georgian, close to the land and to family life, is inclined to be the protector of things as they are and the enemy of violent change. Often he is far more ready to acknowledge the presence of bad conditions than he is to suggest remedies, for he has the conservative feeling that the cure may be worse than the disease. Nevertheless, his political traditions sometimes compel his tacit support of a disturbingly liberal program merely because he cannot bring himself to change his party. In ante bellum and Reconstruction times the Georgian was hot with conviction as he hurried to the ballot box; in the twentieth century a crucial issue is needed to bring out a large poll. Although many citizens of the more populous centers, particularly businessmen, have broken wholly away from the political tradition of the Solid South, many a farmer and small-town merchant preserves a rather bewildered allegiance to his party merely because he finds any other course unthinkable.

This respect for ancestral usage, however, does not impel the Georgian to conceal himself from the modern world. Often he is boldly and genuinely liberal; almost always he responds to innovations that make his life more comfortable and efficient. Perhaps his attitude toward old ways is less one of respect than of an indulgent but unblinking affection. Old houses in Georgia have not been well preserved unless they were also agreeable to live in, and it is only in recent years that organizations in the state have begun to commemorate its historic spots. In most ways the Georgian does not linger long in the shadow of his forbears.

Nor is this condition entirely of modern times. With certain mutations, it is a normal evolution from Colonial days, when the settlers, despite the financial aid extended to them by the trustees, had to rely largely upon their own energy for economic survival. The Georgia colony, created partly as a protective rampart between South Carolina and the hostile Spaniards of Florida, was regarded as a stepsister of South Carolina, peopled by adventurers. Various visiting chroniclers of the early nineteenth century made allusion both favorable and unfavorable to the Georgian’s shrewdness, his readiness to bargain keenly, and his energy in the pursuit of prosperity. Similar comments came from within. The state’s own commentators seemed content to see their ideal embodied in the canny but honest country gentleman of Augustus Baldwin Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes.

The modern prototype of that gentleman, equally robust, is found less frequently on the farm than in the small town. Other types may be more numerous, but none is more important or more characteristic of sectional culture. In this state the big man in a small town is so powerful that in certain communities he has the prerogatives of a patriarch and a dictator. Usually his despotism is benevolent, but it is seldom questioned. In a remote hamlet of south Georgia a stranger who wished to go hunting was informed that he must secure not only a hunting license but also the permission of the town’s leading citizen. This gentleman not only granted that permission but offered free bed and board, and enthusiastically joined the visitor in the hunt. But without this royal consent the reception would not have been so pleasant. Far from resenting his highhanded ways, the autocrat’s friends usually chuckle, “Well, you know how Mr. Ed is.”

Although this Main Street monarch no longer lives on a farm, he usually owns one and is never very far away from it in spirit. If any generalization could be patterned to fit Georgians, it would be that even the most urbane ones have seldom traveled far from plowed fields and country lanes. About two thirds of the state population is actually engaged in agriculture, and the remaining third—although some do not realize it—is powerfully affected by the cotton crop. Rare indeed is the citizen with more than two generations of city life behind him. Even the most hard-driven city banker holds fast to his father’s farm; even the most fashionable urban society takes pleasure in the rural amusements of barbecues, fish fries, and possum hunts. For all its industrial wealth, its factories, and its capital city of bright eastern smartness, Georgia is still an agricultural state.

AMICALOLA FALLS

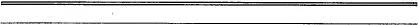

LAKE NACOOCHEE, CHATTAHOOCHEE NATIONAL FOREST

BRASSTOWN BALD, FROM TRAY MOUNTAIN

PROVIDENCE CAVERNS, NEAR LUMPKIN

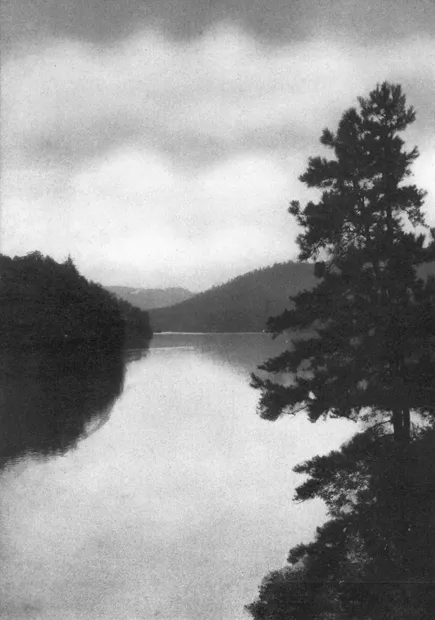

COUNTRY ROAD, NEAR IRWINVILLE

CONTOUR PLOWING ON GEORGIA’S ROLLING UPLANDS

WORM FENCE, BLUE RIDGE MOUNTAINS

WILD DUCKS, SAVANNAH WILDLIFE REFUGE

MINNIE LAKE, OKEFENOKEE SWAMP

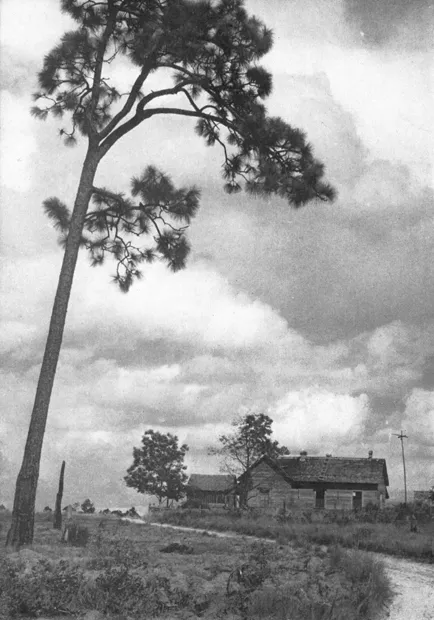

LAKE TRAHLYTA, VOGEL STATE PARK

PALMETTOS NEAR BRUNSWICK

DOGWOOD BLOSSOMS

STONE MOUNTAIN

The wagon-rutted red-clay roads of Georgia are not only farm-to-market but farm-to-courthouse highways; for the rural voter, stoutly fortified by the county-unit electoral system, is a powerful force in state politics. The norm is found neither in the lackadaisical poor-white sharecropper nor in the keen young graduate of a modern agricultural college, but somewhere between these two—in a rangy, slow-speaking man, red with sunburn and a little stiff from outdoor work in all sorts of weather. He gathers with his own kind at the crossroads store, which is often the real seat of legislative decisions. To a stranger asking a direction he is as polite as he is loquacious, very ready to answer with “ma’am” or “sir,” but in argument he is no easier to overcome than his own mule. Riding to town in his rumbling wagon or well-worn Ford, he is quietly aware that his place in the community is an important one. Although many of his kindred and friends have left the farm in poverty, he still keeps it the center of power.

Although the family has felt shattering forces here as elsewhere, there still persists the fierce and tenacious clan loyalty that was so mighty a cohesive force in Colonial society. This quality explains many common phenomena: the interminable “little visits” among brothers and sisters, the tolerance for crabbed uncles and crotchety aunts, the care for old family servants, the vigilance for favors from cousins in high places, the long and intricate tribal conferences whenever a daughter marries or a son changes his job.

Even in Atlanta, least typically southern of southern cities, a host will heartily urge his guests to stay even though he whisper to his wife that night in the bedroom, “How long do you reckon Cousin Annie Mae means to visit us?” Accepting all “kinfolks” as inevitable, he invites them to his daughter’s wedding, which is likely to be a lavish affair with lovely bridesmaids in pastel dresses, and several rooms set aside for the sparkling display of wedding gifts. In their turn, the guests feel bound to send gifts, no matter how slight the actual intimacy. Georgia’s tradition of social obligation seems unlikely to be lost, for it has survived almost intact through the War between the States and the bitter years of poverty that went on even into the new century.

Although Georgians are not “still fighting the Civil War,” they mean that conflict and nothing later when they refer to “the war.” Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind did not arouse, but merely confirmed, the sectional feeling of the old people who remember General Sherman’s march to the sea, and even readers who did not like Scarlett O’Hara or Rhett Butler acclaimed the book for its picture of Georgia plantation life. The fire of sectional resentment no longer flames fiercely, but the invaders are not wholly forgotten. Although Georgia is only beginning to be well adorned with historic markers, the Union invasion has left towering monuments in the minds of its oldest citizens and of their children reared in the years of famine. With each generation the fire burns lower, but it still smoulders enough to make the War between the States a rather dubious topic to be introduced by the northern visitor. Only the most modern young Georgians can discuss impersonally the reasons for the destructive march to the sea.

Georgia’s young people, more widely traveled than their parents, have lost much of their sectional individuality as they have acquired closer resemblance to young people throughout the nation. They have learned to accept many conditions formerly rejected in their state. Their attitude toward the educated Negro, for instance, may be different from that of their elders who still prefer the old-fashioned unlettered kind. The college-bred Negro is likely to be lonely except in Atlanta, the world’s largest center of Negro education, where he finds many of his own kind. The older Georgian generally meets this type with civility but with aloofness, feeling a half-conscious distrust because he has not grown accustomed to the educated Negro’s new and precise enunciation. The rich slurring tones of his old nurse are to him more natural.

But, however cool he may be toward the cause of Negro education, the Georgian is usually kind to his own servants and not a little apprehensive of hurting their feelings. Although many Georgia women do their own housework, many others still employ a general servant who is usually referred to as “the cook.” Likewise, the gardener is called “the yard man.” If these servants have been long with the families which they serve, they are loquacious, assured, and quite capable of showing strong preferences among their masters’ friends. Only very old servants will go so far as to invite their favorites to dinner without first consulting higher authority, but few southern women would be heedless of the warning tone in which a cook mutters, “It’s time you wuz havin’ Miss Grace to supper.”

In Georgia the past and the present sometimes are blended harmoniously, sometimes are separated sharply. Although many parts of the state move slowly, they almost never have that museum stillness which some visitors apparently expect. Change may come very gradually, but it does come, even in decorous Savannah, the most aristocratic of Georgia’s larger cities; and often the younger generation appears more jaunty than it is because of the contrasting quiet background. Even in the villages of the north Georgia mountains is seen the sleek, tightly waved hair of native daughters who have visited the traveling “beautician.” In many ways Georgia has become very much like other states.

Where, then, can a tourist expect to catch the characteristic flavor and experience the real “feel” of Georgia? He will not always find it in Atlanta, sprawling and rich; or in sedate and beautiful Savannah; or in Augusta, where the past is thrown into sharper relief by the smartness of wealthy tourists. Perhaps he will come nearest to finding it in rolling hills of red clay, brown cornfields, white patches of cotton, and green fields of watermelons. He will find it on many a quiet farm, where the plow has left long undulating furrows over the hills, and where, each Saturday, the children sweep the yard very clean and bare. He will find it after church on Sunday, when the young married couples join their parents about a table loaded with fried chicken, ham, hot biscuits, jelly, preserves, and all the vegetables from the garden. Afterward the men smoke and sit on the worm fence, talking crops and politics, and the women gossip on the porch while they watch the children at play.

This characteristic atmosphere may also be caught in the typical Georgia town, where the wide streets are bordered by magnificent trees and a rather sparse planting of grass. Downtown, amid brick shops of the 1880’s and 1890’s, a Confederate soldier of granite or marble leans on his musket as he watches over the quiet courthouse square. Sometimes the passing automobiles are packed tightly with boys and girls in slacks, polo shirts, and sun-back dresses, looking like young people everywhere. Their faces may seem very young to a visitor, for a Georgia girl begins “going out” a year or two earlier than northern girls, so that her debut is less an introduction than a triumphant affirmation of popularity.

In these towns the center of sociability has shifted from the livery stable to the corner drug store, the garage, and the filling station. Spanish mission bungalows and scrollwork cottages have sprung up amid the columned ante bellum houses, and even some of these latter have been modified by additions of bandsaw banisters or screened porches. The porch is a real Georgia institution. Here throughout the summer evenings sit thousands of Georgians, neither rushing into the future nor running away from it, but waiting to accept it as it comes.

![]()

Natural Setting and Resources

GEORGIA, THE largest state east of the Mississippi River, has an area of 59,265 squar...