![]()

1

DEVON

The Background & the Boer War

Countless postcards sent across the nation, and indeed across the world, from Edwardian Devon captured the awesome beauty of its moors and rivers, the attractions of its bustling seaside resorts and high streets, and the glories of its historic castles, churches and mansions. They portrayed a county basking in its ancient landscapes, dramatic past and prosperous present, and they did not lie. And neither did the plethora of guidebooks describing the plethora of leisure attractions and facilities awaiting visitors. But not surprisingly, the truth about Edwardian Devon is far more complicated and a great deal more interesting.

The period 1901–14 is generally known as ‘Edwardian’, even though it includes the first few years of George V’s reign (1910–36) as well as all of Edward VII’s (1901–10). Throughout these years, the Union Jack flew over British imperial possessions across the world, the red ‘duster’ fluttered at the sterns of thousands of British merchantmen and the white ensign announced the arrival of British warships in every ocean and countless ports. But beneath these awesome signs of power and prosperity Great Britain itself was becoming discernibly less sure of its pre-eminence, less confident in its social order and less optimistic about its future.

This book argues that this important period possesses a character of its own, much like Edward possessed a character very different to Victoria and Albert, his parents. Indeed, the Edwardians found that many of the social and political issues vexing the Victorians were now demanding solutions, however controversial and costly those solutions might be. The book examines these turbulent years through the eyes of Devon society with all its variations in wealth, occupations, attitudes and lifestyles, and its primary aim is to highlight the hopes and fears, and convictions and doubts that led the people of Devon to interact as they did. It draws upon the plentiful evidence of the tensions and trends that lies tucked away in museums and archives across the county.

Devon County Council’s minutes record the decisions reached regarding its steadily increasing responsibilities for highways, public health and, after 1903, most elementary and secondary schools. Head teachers’ logbooks give insights into local lives with entries covering syllabuses, standards, inspectors’ reports, managers’ visits, pupil attendances, local epidemics and, sometimes, glimpses of parental attitudes, the gross inadequacies of school facilities and teachers’ joys and frustrations.

Many local newspapers record verbatim, or as verbatim as the reporter and editor decided, the speeches made by the proponents and opponents of every major contemporary question. Most newspapers were avidly partisan, favouring either the Liberal or Conservative Party, but as we shall see, views on the suffragettes, Irish Home Rule and tariff reform often transcended party lines and rendered Edwardian party politics and elections even more confusing than usual. Generally speaking, editors claimed their preferred orators argued eloquently, sincerely and coherently while their opponents were hesitant, repetitive and unconvincing.

The newspapers also contain reports and letters on local sports events, theatre and seaside entertainments, the seasonal condition of agriculture, the many fetes and sales on behalf of charities and political parties, naval and military exercises, church and chapel affairs, court cases and the interminable meetings of school boards, boards of guardians and city, town and borough councils. Advertisements give invaluable information on the range of goods and prices and the frequency of trains and trips by sea.

Other important sources are directories, magazines, pamphlets and memoirs. Kelly’s Directory is a mine of local information, as are the 1891, 1901 and 1911 census summaries. Church magazines provide further evidence of local societies and their aims, clientele and success, as well as the views of the clergy. An array of pamphlets and brochures survive promoting religious and temperance movements, political campaigns, the openings, extension and maintenance of hospitals and mental institutions, and the sales of great houses and estates. The memoirs of Earl Fortescue, Devon’s Edwardian lord lieutenant, contain interesting perspectives on his family’s interests and local trends, and the published and unpublished memories of villagers growing up around the turn of the century throw light, often unconsciously, on the social hierarchies surrounding them as well as the enormous efforts required to keep warm, clean and fed.

The Victorian Background

Queen Victoria reigned from June 1837 to January 1901, and during these sixty-four years her kingdom was buffeted by a bewildering variety of stresses and strains. A host of factories poured out an array of mass-produced goods as well as never-ending billows of smoke, and increasingly powerful locomotives heaved wagons and coaches across the rapidly expanding railway network.

The population almost trebled, and so did the nation’s wealth, with the fanciful mock Gothic houses and fussy parterres of the newly rich matching the ancient, if substantially renovated, mansions and sweeping parkland of the older established grand families. The glittering reception halls and dining rooms were devoted to lavish parties, balls and masques where income and status were flaunted at a time when servants were plentiful and cheap.

The vagaries of markets and investments combined with unfettered expenditure meant that some notable families managed to bankrupt themselves, but there were others all too keen to buy their estates. And all the while the mass of the population crowded into the courts and tenements of the towns and cities or, if they were more fortunate, the serried rows of late Victorian terraced estates springing up on their outskirts. Some of these new houses were plain and flat fronted, and some had decorated brickwork and bay windows, as even working-class homes, like everything else in Victorian Britain, displayed the nuances of a family’s place in the social pecking order. In the middle of the century the urban population outstripped the rural one for the first time, and the gap steadily widened.

Protected by the world’s most powerful navy, British shipping companies and commercial enterprises sought raw materials and markets across the globe, and in doing so the British Empire grew ever larger. Amidst numerous colonial wars, sometimes fought with alarming incompetence although generally successful in the end, large parts of Africa were added to the older established colonies of Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and a racially and politically divided India remained largely secure in British hands despite a bloody rebellion in 1857.

But it was not only trade that made the empire important: as Victoria’s reign drew to a close both France and Germany had become Britain’s bitter rivals in empire building and its concomitant commercial exploitation, and equally important, in the fervent pride they possessed in this essentially Eurocentric age in exerting and flaunting their imperial influence as they jostled for international pre-eminence.

There was much for Victorians to be fearful about as the British economy changed for the better for some but the worse for many others. Towns became overwhelmed by thousands of migrant families lured by the widespread rash of vast new factories exploiting new technologies that offered regular work and wages. Many migrants had little choice as the new technologies, notably in the vast textile trade, rendered cottage industries such as the home-based handloom weavers redundant. Victoria’s reign saw a transformation in the means of production and transportation, and a dramatic rise in consumerism for those who could afford the dazzling array of new domestic furnishings, clothing and gadgets on offer.

From the late 1870s rural conditions deteriorated as the vast plains of North America, India and the Russian Empire poured huge amounts of grain into British ports far more cheaply than it could be produced here. The imports were also tariff free. Arable farmers were forced to sell up, or to seek lower rents if they were tenants and then diversify into new markets and reduce labour costs. As a result yet more country families trudged to the towns to join the earlier migrants, or packed into the ill-serviced emigration ships sailing to North and South America, Australia and New Zealand, and South Africa.

To the growing consternation of Victorian churchmen, humanitarians, local officials and national politicians, the vast working-class areas in the ever-expanding towns appeared as mounting threats to law and order, and to health and morality, with their plethora of slums, public houses, criminal gangs and brothels, and chronic lack of clean water, sewage, churches, police and schools. Charities moved in with varying degrees of generosity, boards of guardians created vast workhouses run with varying degrees of efficiency and humanity, and with varying degrees of success the rival Anglican, Nonconformist and Roman Catholic churches made huge efforts to build places of worship, provide clergy and attract new congregations. Gradually, too, public health authorities sought to cleanse and drain the streets, but all these tasks were far from complete at the turn of the century, and abject poverty, overcrowding and epidemics remained commonplace.

Poverty was endemic in both town and country, and many working families’ wages provided a mere subsistence standard of living that was always under threat from death or disease removing one of the wage earners, be it the husband, wife or older children.

The very poor had two sources of support – local charities drawing funds from legacies and subscriptions, and boards of guardians drawing on the rates. The former varied widely in their availability, resources and willingness to support those they suspected of being feckless or dissolute; the latter were as much guardians of ratepayers’ pockets as they were of the poor, and the stigma of being labelled a ‘pauper’, along with the workhouse uniform and discipline, went a long way to ensure that only those who had fallen to the very bottom of the social scale applied for admission.

Many upper and middle-class commentators were scathing in their indictment of the poorest members of the working classes as being largely responsible through drink, idleness and debauchery for their own misery. Many people also found the idea of the State intervening in essentially private family affairs abhorrent on ethical grounds. Such widely held views clashed vehemently within and beyond the Houses of Parliament with contrary arguments put forward by reformers for a greater degree of State support for those who had fallen on hard times – often, they boldly claimed, through no fault of their own. Arguments attempting to define ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor and surrounding the right and duty of the State to interfere in people’s lives, and the likely expense, raged to and fro throughout the nineteenth century, and in doing so prevented more than minimal welfare legislation passing into law.

Victorian Britain was never free from popular dissent and protest; indeed it was a violent age. The angry but futile protests of the handloom weavers against the machines of the textile magnates had been mirrored in the 1830s by the equally unsuccessful attacks of rural workers on the new threshing machines. Huge civil disturbances accompanied the campaign for electoral reform before the 1832 Franchise Act was grudgingly passed and also the Anti-Corn Law crusade which secured the abolition of import duties in the 1840s. Around the same time the Chartist movement fought aggressively, but ultimately unsuccessfully, for even greater parliamentary reforms, notably universal male suffrage, secret ballots and the removal of property qualifications for parliamentary candidates. Election contests were often violent, and accusations of corruption were commonplace and often proved justified.

By 1901 two further bitterly contested reform acts in 1867 and 1884 had extended the vote down the social scale to 60 per cent of adult males, and parliamentary constituencies had been substantially realigned to ensure their more even distribution. As each bill struggled to become law many politicians and commentators prophesied the downfall of constitutional government and the degeneration of politics into outright class warfare. As we shall see, such Jeremiahs were not completely wide of the mark, but were no doubt comforted as the new century approached that although women could vote in local school board and board of guardians elections, and even become members of them, they remained firmly barred from voting in general elections.

Nevertheless, virtually all of Britain’s national institutions, and most notably the House of Lords, were soon to be subject to immense and prolonged public scrutiny and criticism. And thrown into the boiling cauldron of Edwardian controversies were the additional and equally hotly contested issues of giving women the vote, finally granting Ireland Home Rule and imposing tariffs on foreign imports.

The deep antipathies between the Church of England and the various Nonconformist sects became more sharply focused, especially over working-class education as it became inextricably entangled in economic, sectarian and political arguments over its value, cost and content. In Devon, as elsewhere, most, but not all, Anglicans leaned towards the Conservatives, and most, but not all, Nonconformists preferred the Liberals. As we shall see, the various overlapping alliances proved a recipe for even more confusion and bitterness.

If the period’s newspapers are to be believed, everyone had views on all these issues. The people of Devon were certainly actively engaged in every trauma, as the verbal and intermittent physical violence characterising the keenly fought general elections revealed. Change, ominous to some but welcome to others, was said to be ‘in the air’. Liberals and Conservatives largely agreed that things were not as they should be – though not, of course, on the causes or the solutions. As Hamlet said of Elsinore – ‘the times are out of joint’.

The Long Shadow of the Boer War

The final war in the long list of wars in Queen Victoria’s reign heightened the relevance of Hamlet’s bitter assessment, and cast a lengthy shadow over both home and overseas affairs throughout the Edwardian era. It was fought against the small Dutch-Boer controlled republics of the Orange Free State and Transvaal in South Africa, and lasted from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 – far longer than anyone in Great Britain anticipated. In this respect it foreshadowed the greater conflict in 1914, a mere dozen years later.

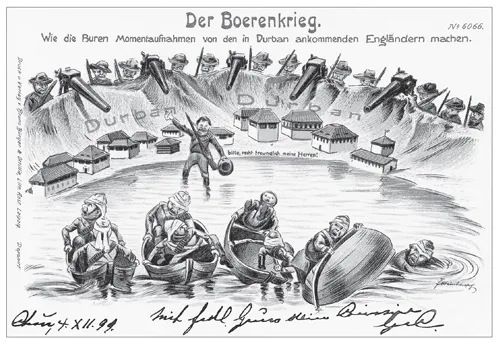

German pro-Boer postcard mocking British military prowess, 1899. The caption reads, ‘How the Boers take snapshots of the British army arriving in Durban’. (Author’s collection)

Diamonds and gold had been discovered in the two Boer republics some years earlier, and their lure had intensified the long-standing antipathies between the independent-minded Boer leadership and British aspirations to control the whole of southern Africa. Great Britain won the war, but the price was heavy. Over 21,000 British, Canadian, New Zealand and Australian soldiers died in battle or from disease. Just over 9,000 Boer combatants died, but so did 28,000 white civilians and unknown thousands of black Africans.

The war had three phases, each of them casting grave doubts on British military competence, political sagacity and moral integrity. At the outset, the Boers struck rapidly into British-held Natal and Cape Colony, and laid siege to Ladysmith, Mafekin...