eBook - ePub

The Portsmouth Dockyard Story

From 1212 to the Present Day

Paul Brown

This is a test

Share book

- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Portsmouth Dockyard Story

From 1212 to the Present Day

Paul Brown

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

From muddy creek to naval-industrial powerhouse; from constructing wooden walls to building Dreadnoughts; from maintaining King John's galleys to servicing the enormous new Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers: this is the story of Portsmouth Dockyard. Respected maritime historian Paul Brown's unique 800-year history of what was once the largest industrial organisation in the world is a combination of extensive original research and stunning images. The most comprehensive history of the dockyard to date, it is sure to become the definitive work on this important heritage site and modern naval base.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Portsmouth Dockyard Story an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Portsmouth Dockyard Story by Paul Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnologia e ingegneria & Trasporti marittimi. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Trasporti marittimi1

BEGINNINGS

We order you, without delay, by the view of lawful men, to cause our Docks at Portsmouth to be enclosed with a Good and Strong Wall … for the preservation of our Ships and Galleys.

King John to the Sheriff of Southampton, 20 May 1212

Portsmouth as a city or town has long been defined by its dockyard, whose history can be traced back over 800 years. The natural sheltered harbour there has for many centuries provided a haven for the Navy and a port of embarkation for successive armies. It is complemented by the anchorage at Spithead which, like the harbour entrance, is shielded by the Isle of Wight from the prevailing south-westerly winds. These advantages have led to 2,000 years of maritime activity there, and to Portsmouth’s role as Britain’s most important naval port during crucial periods in its history.

The Romans built a stronghold at Portchester in the third century as part of a chain of forts from Brancaster (in Norfolk) to Portchester, and this site was possibly the one named Portus Adurni. Building activities probably began in the late third century around the time when the corrupt naval commander Carausius seized independent power in Britain, and he or his successor, Allectus, may have been responsible for constructing the fort at Portchester.1 It has the most complete Roman walls in Northern Europe. They are 20ft thick, and the front face contains bastions which accommodated ballista (Roman catapults). By AD 501, the Roman occupation had declined and Portchester may have been used by the Saxons as a defence against Viking attacks, until some control was gained by the ships of King Alfred and his successors in the late ninth and tenth centuries.

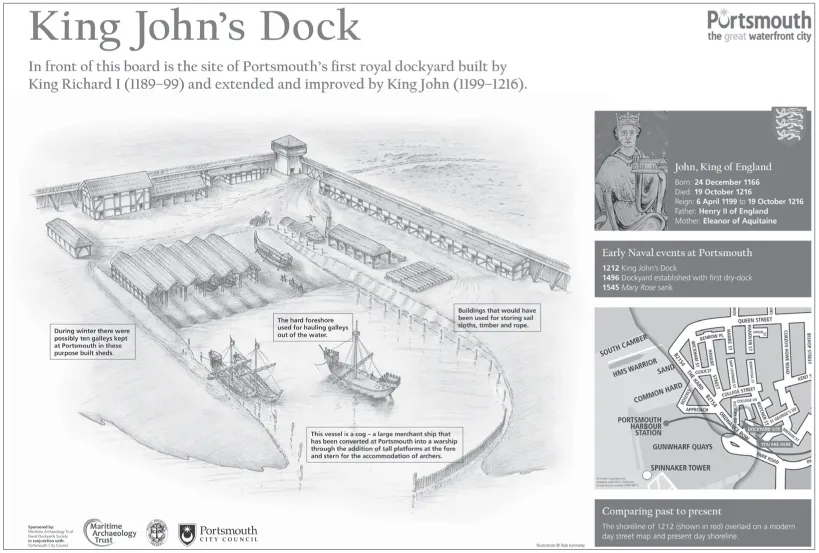

King John’s Dockyard

Henry I built a castle within the Roman walls at Portchester and embarked from Portsmouth on several occasions for Normandy, as did his grandson, Henry II, in 1174. After Henry II’s death in 1189, his eldest surviving son, Richard the Lionheart, landed at Portsmouth as King of England.2 However, around this time Portchester was eclipsed by the rise of the new town called Portsmouth: this may have been due to a change in tidal behaviour and sedimentation associated with the onset of the medieval warm period. Reduced flow in the Wallington River and variation in channel patterns could have induced significant changes along the Portchester shoreline, causing maritime activities to be shifted to the mouth of the harbour.3 In 1194, King Richard I granted a charter to Portsmouth and ordered the building of a dock in the area called the Pond of the Abbess, at the mouth of the first creek on the eastern side of the harbour, which was later to become the site of the Gunwharf. Here ships could anchor, and on the creek’s mudflats they could be hauled out of the water for repair or cleaning. Richard needed an alternative port to Southampton to be free of the powerful merchants and their high taxes. He needed this for his royal ships, the warships of a small fleet that travelled between England and his possessions in France.4

The dock was enclosed by order dated 20 May of Richard’s brother, King John, in 1212:

The King to the Sheriff of Southampton. We order you, without delay, by the view of lawful men, to cause our Docks at Portsmouth to be enclosed with a Good and Strong Wall in such a manner as our beloved and faithful William, Archdeacon of Taunton will tell you, for the preservation of our Ships and Galleys: and Likewise to cause penthouses to be made to the same walls, as the same Archdeacon will also tell you, in which all our ships tackle may be safely kept, and use as much dispatch as you can in order that the same may be completed this summer, lest in the ensuing winter our ships and Galleys, and their Rigging, should incur any damage by your default; and when we know the cost it shall be accounted to you.

By implication some sort of facility already existed before William of Wrotham, Keeper and Governor of the King’s Ships (and Archdeacon of Taunton), started to build his walls and the lean-to sheds to store ships’ tackle and rigging. These events are seen to mark the founding of the first dockyard at Portsmouth, which now became a principal naval port, superseding the Cinque Ports.5 We do not know what form the docks took. It is possible that a lock was built near the high water mark, and blocked with timber, brush, mud and clay walls at low tide, with a wooden breakwater, a stone wall to protect it and penthouses to store sails and ships’ equipment. The lock may have been built of stone and led into a non-tidal wet dock or basin.6

Alternatively, there may only have been temporary mud docks with ships being dragged and docked as far up as possible on the mud at the head of the creek at high water, then closed off from the next flood tide by a wall across the creek.7 Such mud docks may have been complemented by a tidal basin in which ships could lie afloat and also be hauled out onto a slipway, as shown in the illustration. It was from this dockyard in 1213 that King John’s royal fleet of galleys joined more galleys from the Cinque Ports to achieve the first great naval victory over the French, at the Battle of the Damme.8 A fleet led by the king sailed early in 1214 for La Rochelle and Bordeaux in an unsuccessful attempt to regain lost territory in France. Around 1228, but not for the first time, the dock was badly damaged by storms and high spring tides. It may have been this that caused Henry III in 1228 to command the Constable of Rochester ‘to provide wood to fill up the basin and to make another causeway there, notwithstanding that King John had caused walls to be built close by for the protection of his vessels from storms’.9 The dock was abandoned, and in 1253 Henry III demolished the wall and reused the stone to repair his town house.10 Tentative evidence of the dock’s location has led to the erection of a display board at the supposed site in St George’s Square, Portsea. It seems that, given the paucity of sea defences at the time, the dock had not been well sited and subsequent naval docks would be built further up-harbour.

The displayboard in St George’s Square, showing an artist’s impression of King John’s Dock in 1212. It was from here that King John’s royal fleet of galleys joined more galleys from the Cinque Ports to achieve the first great naval victory over the French at the Battle of the Damme. Building of the dock had been instigated by King Richard I, who needed an alternative port to Southampton to be free of the powerful merchants and their high taxes. (Rob Kennedy)

Despite the lack of enclosed docks, Portsmouth was used to prepare expeditions to France by Henry III, and in 1346 Edward III sailed from the port with a fleet for Normandy and victory at the Battle of Crecy.11 In 1415, King Henry V assembled his fleet at Portsmouth and Southampton, and, embarking from Portchester Castle, sailed for France and the Battle of Agincourt. On his return, he ordered the building of the Round Tower, beginning the construction of the port’s defences. He also purchased land to the north of the old docks for the construction of ‘The King’s Dock’12 but, following his death in 1422, it was not built and most of the king’s ships were sold.

The Tudor Dockyard

The next, and highly significant, event was the ordering in 1495 by King Henry VII of what is believed to be the country’s first dry dock. This was to be built on the land that Henry V had bought, in the area now occupied by No.1 Basin, and marked the founding of the current naval dockyard at Portsmouth. It was built to accommodate the Sovereign and Regent, which were bigger than their predecessors. They both drew too much water to go far up, or possibly even enter, the River Hamble, which had been used for laying up ships of Henry V’s navy: this may have been one reason for the adoption of Portsmouth for the new dockyard. The designer of the dock was possibly Sir Reginald Bray, one of the trusted councillors of Henry VII, who had been made Treasurer at War and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. He was also an architect and has been credited with St George’s Chapel at Windsor and Henry VII’s Chapel at Westminster. In 1488, he was requested by Henry VII to dismantle the ship Henry Grace à Dieu and from the pieces construct a new ship to be called the Sovereign, having a displacement of 600 tons and carrying 141 serpentine cannon. It was this ship that was the first to use the new dock. The practice of dismantling wooden ships and building a new one from the pieces was a common practice and continued well into the eighteenth century. The task of overseeing the new dock fell to Robert Brygandyne, a yeoman of the Crown who had been appointed Clerk of the Ships (as the post once held by William of Wrotham was now known) in May 1495, as officer in charge of construction.13

Work on the dock began on 14 July 1495 and continued until 29 November, when it stopped for the winter. In this period the dock was dug out and the sides fixed: the sides were backed by stone and lined with wood, 158 loads of timber being used. Work started again on 2 February 1496, when the great gates were built using 113 loads of timber, which were sawn into 4,524ft of planking. These gates were then hung, being staggered in their position at the entrance to the dock and reaching across its width. The intervening space was filled with clay and shingle to form a watertight middle dam. All work was completed by 17 April 1496, and Brygandyne accounted for every payment made, the cost of construction being £193 0s 6¾d: this sum covered the wages and victuals of carpenters, sawyers, smiths, labourers, carters with their horses and a surveyor, and provision of timber, stones, clay and ‘other stuff for the work’. Carpenters and smiths had to be obtained from Kent because they were not available in Portsmouth. Brygandyne also made an inventory, including smithy bellows, lanterns, caulking irons, chains, pick-axes and other items required for the operation of the dock.14 Then came the great day on 25 May 1496 when the Sovereign entered the dry dock. Once in the dock, after gravity drainage at low tide, the entrance was sealed with the wooden gates and clay, and the remaining water was then pumped out using a bucket and chain pump worked by a horse-gin. It took between 120–140 men who were employed for a day and a night before the operation was complete. The majority of the men were employed on infilling with the clay and shingle. Getting the ship out of the dock on 31 January 1497 was a more lengthy procedure, as all the impacted clay and shingle had to be removed from between the great gates before they could be opened, and we are told it took twenty men twenty-four days to open them.15 The Sovereign was fitted out for a chartered trading voyage to the Levant, and as soon as the she was out the Regent went in to be fitted out for service on the Scottish coast.16

Although the precise site of the dock is not known, it is generally thought to have been about 50ft astern of where HMS Victory lies today in No. 2 Dock. During the enlargement of the Great Ship Basin in late 1790s, the remains of an ancient dry dock were discovered in that position. However, it is possible that these remains may be from one of the seventeenth-century dry docks, although its construction w...