![]()

1

Backstory

Every great story has a backstory. Star Wars would not be Star Wars without “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . . .” scrolling up the bottom of the movie screen at the beginning. Superman would be puzzling without the knowledge that he was born Kai-El on the planet Krypton, came to Earth in a spaceship, and was adopted by a Kansas farmer and his wife. Citizen Kane makes no sense at all without Rosebud. Actors consider the backstories of their characters so important that they will make them up if the script fails to provide them. These histories are important because they make characters three-dimensional and believable. By rendering the history of events, they make plots and conflicts understandable and more compelling. In short, they set the scene for what is to come.

The story I tell in the chapters that follow has a backstory too. I began visiting newsrooms in the winter of 2004–5, and most of the action I describe takes place between then and the summer of 2009. But the people I met and the newsrooms within which they work existed long before my entrance. To truly understand this story – the motivations and actions of the people, the conflicts and prejudices at work in newsrooms – we need to learn something of their backstories.

As a start, consider the following article from the Los Angeles Times. The headline reads “Newspapers challenged as never before,” and the lead asks, “Are you holding an endangered species in your hands?” The rest of the story documents the industry’s woes, which include flattening circulation, a sharp drop in market penetration, plunging advertising revenue, and the closure of many newspapers. It is not inconceivable, the author concludes, that the entire industry could simply die. “If we’re not careful,” he quotes one editor as saying, “we could find ourselves in the buggywhip business; we could phase ourselves right out of existence.” Given the industry’s recent woes, you might think this story was published in the last few years. In fact, however, it was published in 1976, twenty years before the Internet made its way into most newsrooms (Shaw, 1976). That fact is a central part of the backstory to contemporary newsrooms. Journalists were worrying about their future, wondering if the newspaper industry would survive, and working feverishly to reverse their fortunes for twenty years before the Internet made its arrival in newsrooms.

They were also dealing with the corporatization of their newsrooms – another crucial element of the backstory to the modern newspaper industry. Corporate chains have been around since the 1880s, but until very recently they played a minor role in the news industry. Through the twentieth century, most urban dailies were family-run businesses. In 1960, for instance, corporate chains owned only 30 percent of daily newspapers. By the mid-1990s however, the proportion of newspapers owned by corporate chains had jumped to 75 percent, and the family-run newspaper had largely gone away. Corporate newspapers were different sorts of animals than family-owned newspapers. Most obviously, in corporate newspapers the bottom line was more often the bottom line. A story, perhaps apocryphal, but often told by journalists, has it that the Bingham family, which owned the Louisville Courier through much of the twentieth century, got by on profit margins as thin as 5 percent. In the 1990s, no self-respecting corporate chain made less than a 20 percent profit margin, and many made a yearly profit of as much as 30 to 40 percent.

Such profit pressures changed the culture of journalism in profound ways. In the midst of a long-term decline in market penetration, they were being asked by new corporate bosses to achieve heretofore unheard of profits for their companies. The effort to solve these problems simultaneously caused a great rift in the culture of journalism. Should journalists give readers what they want in the news? What about what readers need from the news? Would giving them what they want be mere pandering? What would it do to the public service mission of journalism? Who should decide these issues – corporate bosses or journalists? Such questions consumed journalists in these years. The very urgency of the questions forced individuals to take sides. On the one side, corporate managers pressured journalists to be more attentive to reader interests. On the other, editors and reporters held fast to their public service mission. By the people involved, this battle was felt to be over the very heart and soul of the profession, and was fought with these stakes in mind. It too is an important part of the backstory I wish to tell.

Long-term decline, commercialization, and corporatization: these are the crucial elements to the backstory of contemporary journalism. The rest of this chapter sketches these elements in greater detail. If you feel that you grasp this history already, you might skip ahead to chapter 2. But for those who are unacquainted with this backstory, sit back and prepare to enter the story of the modern newsroom (just imagine the text scrolling up from the bottom of the paper).

An Industry in Decline

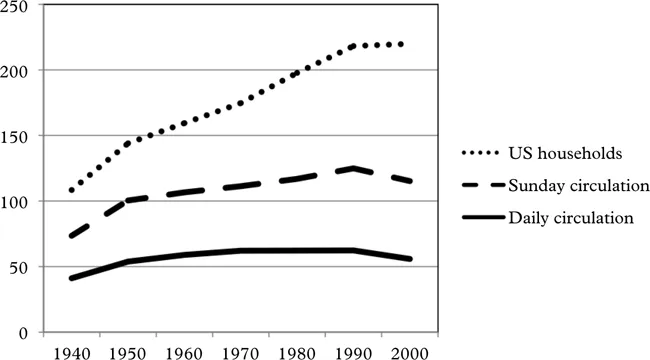

The problem that plagued metro daily newspapers beginning in the 1970s is relatively simple to describe: circulation remained flat while the number of Americans dramatically increased. According to numbers collected by the Newspaper Association of America, average daily circulation for all US daily newspapers from 1960 to 1995 never reached higher than 62,000 and never went below 58,000.3 It remained, in other words, basically flat. Over the same time span, the American population nearly doubled, from roughly 132,165,000 in 1940 to 281,422,000 in 2000. Of course, not every one of these new Americans was likely to buy a newspaper. Children, for instance, do not subscribe to newspapers; nor do prisoners or people in mental health facilities. For this reason, industry experts use households rather than individuals as the basic unit of consumption for a newspaper. Combine circulation numbers with the number of households over time and the trends are clear (see figure 1.1). While daily newspaper circulation has not increased, the number of households has mushroomed, from 35 million in 1940 to over 100 million by 2000. In 1940, nearly every American household took at least the Sunday newspaper. By 2000, that number had been cut in half – and it has continued to fall in the twenty-first century. Put another way, in the last fifty years, newspapers have lost half of their market penetration.

These trends have not been lost on the industry. In fact, people like Leo Bogart, a pioneer in newspaper audience research, were already worrying about them in the early 1960s. Bogart worked for the Audit Bureau of Circulation, an organization founded in 1916 to track circulation numbers for all manner of print publications. In his post at the bureau, Bogart performed some of the first systematic nationwide reviews of newspaper circulation. In his initial survey, conducted in 1961, he found that 80 percent of Americans read a paper on a typical weekday. Naturally, the industry trumpeted this number to advertisers. Their product was nearly universally consumed! But, in the ensuing years, Bogart kept counting, and very soon the numbers began to flatten. The bureau spun this relative decline in different ways. They counted circulation among what they called the “active” adult population rather than the total population. They changed their standard metric from circulation to readership. But, no matter how they massaged the numbers, the lines on the graph still went in the same direction: “the growth of newspaper circulation had slowed down, while the number of households had continued to grow” (Bogart, 1991, p. 36). In 1964, Bogart proposed that the bureau convene a “high-level two-day seminar” at which publishers and others would ruminate on the brewing troubles in the industry. His proposal was not accepted, in part because publishers were squeamish about airing their troubles in public. But a decade later, Bogart reports, “the subject of falling circulation and readership [had reached] a crescendo” in the industry (ibid., p. 66). The trends could no longer be ignored.

Figure 1.1 US daily newspaper circulation vs. number of households (in millions)

Why is our Audience Shrinking?

In the mid-1970s, researchers in industry and the academy got serious about diagnosing the decline of the daily newspaper. The Newspaper Readership Project – a joint creation of the Newspaper Advertising Bureau (NAB) and the American Newspapers Publishers Association (ANPA) – played a prominent role in these efforts. From 1977 to 1983, researchers associated with this project – including Leo Bogart – collected an enormous array of data. They surveyed readers and nonreaders. They asked members of every significant demographic group what they wanted out of a newspaper. They examined different sorts of news content for how well they attracted different kinds of readers. They talked with editors and journalists. They studied the influence on readership of everything from recruitment of newspaper carriers to newspaper design. And they created a “News Research Center” to warehouse these data.

Their analysis of the data indicated that circulation decline was mostly a structural matter, having to do with societal trends that were decades in the making. Suburbanization was the primary culprit. The urban daily newspaper had risen with the growth of cities in the first half of the twentieth century. But in the 1950s people began to move to the suburbs in large numbers, and the population of cities declined. Phyllis Kaniss (1991) reports that, in 1940, the city of Philadelphia contained 60 percent of the area’s population, a number that had dropped to 36 percent by 1980. In 1940, 68 percent of people who lived in the area called Detroit home, but in 1980 only 28 per cent of them remained in the city’s core. The rest had moved to the surrounding suburbs (1991, pp. 23–5). The same trend was happening everywhere, especially in Southern and Western cities (e.g., Atlanta, Houston, Las Vegas, San Diego, Phoenix), to which more of the country’s population was migrating.

Suburbanization had ripple effects for the newspaper industry. At one level, it meant that fewer people were interested in news of city life. What interest did I have in urban crime when I lived 30 miles away? Why should I care what the city mayor was doing (or not doing) when my suburb had its own government? Suburbanization also changed the commuting habits of readers. Suburbanites who commuted to the city for work increasingly drove rather than used public transportation, which meant that they had less time to read a newspaper. Suburbs also siphoned economic activity from cities. Jobs followed people out to the suburbs, and with those jobs went the consumers who once frequented central city businesses – precisely the businesses that newspapers depended upon for advertising revenue. Though the suburban economy grew, urban newspapers were not well positioned to serve the needs of these new businesses. The newspaper offered a scattershot audience spread across the region, while suburban businesses were often interested only in the very specific audience located in their areas. Overall, the urban newspaper fit awkwardly in an increasingly suburbanized landscape, failing to meet the interests and needs of audiences and businesses alike.

New suburban newspapers and weeklies emerged to fill these gaps, and this new competition further eroded the market penetration of metro dailies. In Philadelphia, for instance, while the circulation of metro newspapers shrunk from 1.3 million in 1940 to 763,000 in 1988, suburban newspaper circulation rose from 147,000 to 461,000 (Kaniss, 1991, pp. 30–1). In an influential study of the San Francisco region, James Rosse (1975) found at least four layers of competition in the newspaper market: the urban newspaper (the San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Examiner), the satellite newspaper (the San Jose Mercury News and the Oakland Tribune), the suburban newspaper (the Hayward Daily Review, the San Rafael Independent-Journal, the Berkeley Gazette), and a fourth layer “of once, twice, or thrice weeklies, quasi-newspaper shopping guides, free distribution, partial distribution or throw-away publications, etc.” (1975, p. 149). As the large dailies in the region, the Chronicle and the Examiner had some market share at every geographic level, but their penetration in local markets lagged behind the newspaper or weekly that directly served these communities. The San Jose Mercury News, for instance, had a greater market penetration in San Jose, even though the Chronicle was also available there. The Oakland Tribune garnered some readers in Hayward, but did not enjoy the levels of circulation density obtained by the Daily Review. Rosse called the resulting structure an “umbrella” in which each kind of newspaper thrived in the shadow of the larger newspapers that loomed above it. These newspapers did not so much compete with one another as carve the region into larger and smaller fiefdoms. For the large urban daily, the ultimate consequence was more competition for the attention of suburban consumers and less overall market penetration. It did not help that the cost of reaching those consumers was much higher for urban dailies. The suburbs were stretched across long distances. Reaching them required more trucks, more drivers of those trucks, more gas, and more time to reach their destinations.

In several ways, then, suburbanization loosened the grip of urban dailies on both readers and advertisers. But suburbs alone did not kill newspaper circulation. They had help from other social trends, the most important of which may have been the generational shift away from newspapers that began in the 1960s. Phillip Meyer (2004) reports that, since the early twentieth century, each age cohort has read newspapers less than the last. When they were young, roughly 70 per cent of the “Great Generation” read a newspaper on a daily basis. In contrast, only 30 percent of their children read a daily newspaper, and for their grandchildren the number dipped to just over 20 percent. Today, something less than 20 percent of the millennial generation reads a daily newspaper. To Meyer, the meaning of these numbers is clear: “The true source of . . . readership decline,” he argues, “is a matter of generational replacement. Since the baby boomers came of age, we have known that younger people read newspapers less than older people” (2004, p. 17).4 For a long time, industry leaders argued that young people would pick up the habit as they got older, had children, put down roots in a community, and so on. But this never happened. Instead, in each generation, lower percentages of young people turned to newspapers, and, if they didn’t read a newspaper when they were young, they never picked up the habit.

The reasons for this generational attrition are complicated, but certainly an increase in information choices is one part of the answer. Baby boomers were the first TV generation. “Generation X” had cable television and its hundreds of channels, and was the first generation introduced to video games. In quick order, access to video games, movies, and music exploded to consume more and more of people’s attention. A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation (2010) finds that, today, young people aged eight to eighteen consume over seven hours of entertainment media – more time then they spend on any other “activity” except sleep. Clearly, seven hours of listening to music, watching television, browsing the Internet, and playing video games leaves less time for newspaper consumption. But the issue isn’t just one of numbers. As David Mindich (2004) found in his interviews with young people, when news is put up against video games and TV shows, it is seen as just another form of entertainment (pp. 47–8). Viewed in this light, newspapers are not nearly as much fun as Modern Warfare or the Oprah Show. More people will naturally gravitate to information options that take less effort and are perceived as more fun. Perhaps the question isn’t why fewer young people read a newspaper, but why any choose to do so at all.

Two other social trends that affected newspaper readership are worth mentioning. The first is the increase in female employment that took place in the second half of the twentieth century. In the 1950s, only 34 percent of women worked, a number that had doubled to nearly 70 percent by the year 2000 (e.g., Toossi, 2002, p. 18). This move into the workforce gave women more freedom and opportunity, and, as the incomes of men flattened and even declined somewhat, it allowed families to sustain a middle-class lifestyle. It did not have such salutary effects on newspaper reading. The increase in female employment accelerated the pace of family life in ways that made sitting down to read a newspaper seem indulgent, if not impossible. Studies conducted for the newspaper industry throughout the 1980s showed a steep decline in women readers. The National Advertising Bureau reported the percentage of daily female readers of newspapers dropped 18 percent between 1970 and 1990 (compared with a 12 percent decline in male readers). Other reports put the decline even higher. “Had we maintained our appeal to women equal to what it was in 1970,” one Knight-Ridder report claimed, “we would have seventeen million more readers today” (Harp, 2007, pp. 53–4).

Changes in the public culture also played a role in the decline of newspaper reading. In particular, beginning in the 1960s, public trust in major public institutions declined significantly. Survey data show that Americans’ faith in government, corporations, banks, labor unions, lawyers, doctors, universities, and public schools declined in equal measure (e.g., Lipset and Schneider, 1987). Government took a particularly hard hit. Joseph Nye (1997) reports that, in 1964, 75 percent of Americans said they trusted the federal government to “do the right thing most of the time.” By the late 1990s, that number had dropped to 35 percent, and was even lower in some polls (19...