eBook - ePub

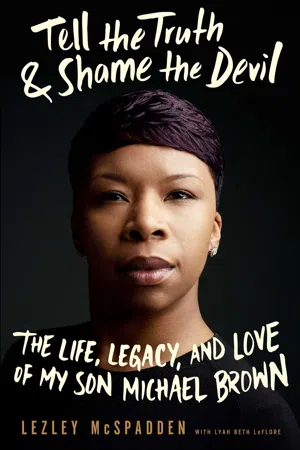

Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil

The Life, Legacy, and Love of My Son Michael Brown

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil

The Life, Legacy, and Love of My Son Michael Brown

About this book

The revelatory memoir of Lezley McSpadden—the mother of Michael Brown, the African-American teenager killed by the police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9, 2014—sheds light on one of the landmark events in recent history.

“I wasn’t there when Mike Mike was shot. I didn’t see him fall or take his last breath, but as his mother, I do know one thing better than anyone, and that’s how to tell my son’s story, and the journey we shared together as mother and son." —Lezley McSpadden

When Michael Orlandus Darrion Brown was born, he was adored and doted on by his aunts, uncles, grandparents, his father, and most of all by his sixteen-year-old mother, who nicknamed him Mike Mike. McSpadden never imagined that her son’s name would inspire the resounding chants of protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, and ignite the global conversation about the disparities in the American policing system. In Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil, McSpadden picks up the pieces of the tragedy that shook her life and the country to their core and reveals the unforgettable story of her life, her son, and their truth.

Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil is a riveting family memoir about the journey of a young woman, triumphing over insurmountable obstacles, and learning to become a good mother. With brutal honesty, McSpadden brings us inside her experiences being raised by a hardworking, single mother; her pregnancy at age fifteen and the painful subsequent decision to drop out of school to support her son; how she survived domestic abuse; and her unwavering commitment to raising four strong and healthy children, even if it meant doing so on her own. McSpadden writes passionately about the hours, days, and months after her son was shot to death by Officer Darren Wilson, recounting her time on the ground with peaceful protestors, how she was treated by police and city officials, and how she felt in the gut-wrenching moment when the grand jury announced it would not indict the man who had killed her son.

After the system failed to deliver justice to Michael Brown, McSpadden and thousands of others across America took it upon themselves to carry on his legacy in the fight against injustice and racism. Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil is a portrait of our time, an urgent call to action, and a moving testament to the undying bond between mothers and sons.

“I wasn’t there when Mike Mike was shot. I didn’t see him fall or take his last breath, but as his mother, I do know one thing better than anyone, and that’s how to tell my son’s story, and the journey we shared together as mother and son." —Lezley McSpadden

When Michael Orlandus Darrion Brown was born, he was adored and doted on by his aunts, uncles, grandparents, his father, and most of all by his sixteen-year-old mother, who nicknamed him Mike Mike. McSpadden never imagined that her son’s name would inspire the resounding chants of protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, and ignite the global conversation about the disparities in the American policing system. In Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil, McSpadden picks up the pieces of the tragedy that shook her life and the country to their core and reveals the unforgettable story of her life, her son, and their truth.

Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil is a riveting family memoir about the journey of a young woman, triumphing over insurmountable obstacles, and learning to become a good mother. With brutal honesty, McSpadden brings us inside her experiences being raised by a hardworking, single mother; her pregnancy at age fifteen and the painful subsequent decision to drop out of school to support her son; how she survived domestic abuse; and her unwavering commitment to raising four strong and healthy children, even if it meant doing so on her own. McSpadden writes passionately about the hours, days, and months after her son was shot to death by Officer Darren Wilson, recounting her time on the ground with peaceful protestors, how she was treated by police and city officials, and how she felt in the gut-wrenching moment when the grand jury announced it would not indict the man who had killed her son.

After the system failed to deliver justice to Michael Brown, McSpadden and thousands of others across America took it upon themselves to carry on his legacy in the fight against injustice and racism. Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil is a portrait of our time, an urgent call to action, and a moving testament to the undying bond between mothers and sons.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil by Lezley McSpadden,Lyah Beth LeFlore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

MY TRUTH

First off, I don’t tell lies because I can’t keep up with them. My grandmother always said, “Don’t lie. Tell the truth and shame the devil.” She considered a lie a curse word and would be like, “Believe what you see and none of what you heard.” Your word is what you still got when you don’t have any money. That’s why if I give you my word, say I’m going do something, or tell you I got you, then I’m ten toes down. Anybody who knows me for real knows that. Feel me?

So that’s why I have to say this to the world, and I want you to hear me loud and clear. Never mind what you’ve heard or think you know about Michael Brown, or about me, for that matter. You don’t know about Mike Mike. You don’t know about me. Now, you might know something, some snippet, some half a moment in time, but you don’t know my son’s life and what it meant, and an eighteen-second video doesn’t tell you anything about eighteen years.

See, before the news media and the nation first heard the name Michael Brown, he was just Mike Mike to me. That’s what we called him. Everybody thinks he was a junior, but he wasn’t. Even though he had his daddy’s first and last name, his full name was Michael Orlandus Darrion Brown. I wanted my son to have his own identity, so he did.

From the moment Mike Mike was born, I knew my life had changed forever. I was sixteen years old with an infant. I didn’t know what kind of mother I was going to be. But when I held him in my arms for the first time and felt his soft skin, he opened his eyes, and I could see my reflection in his little pupils. I suddenly wasn’t scared anymore. It was like we were communicating with each other without words. I was saying, “I got your back, baby,” and he was saying, “I got yours, too, Mama.”

I can’t just say he was mine, though. When Mike Mike was born, he was adored, doted on, and loved by me and his daddy, my siblings, and his grandparents on both sides, who helped with his rearing. He was our beautiful, unplanned surprise—my first son, a first grandson, and the first nephew in my family.

And then, one day our Mike Mike was shot and killed by a police officer on Canfield Drive in Ferguson, Missouri, and suddenly his name was being spoken everywhere: Mike Brown Jr., Michael Brown, or just Brown . . . but never Mike Mike, never our family’s name for him, the name that marked him as special to us and those who knew him for real.

Pastor Creflo Dollar asked me what I thought about all the people out there on Canfield Drive when I got to the scene the day Mike Mike was shot. I turned, looking directly at him, and as sure as the breath I’m breathing, in a very matter-of-fact way, said, “I didn’t see those people. That day, I was looking for one person: my son. Nobody else mattered.”

I think I kind of shocked Pastor Dollar. I was respectful, of course, but I had to tell it to him straight up. I was just keeping it real. You see, because as a mother when your child is hurt, scared, or in danger, you hurt, you want to comfort them, and you will protect them from harm, even if it means laying your own life down. That day out on Canfield Drive, I had tunnel vision. Nothing and nobody was more important than getting to Mike Mike and helping him in any way I could.

It wasn’t until days later, when I looked at the news and people showed me pictures from their phones that I saw the crowd of folks that had been out there. So the only way I can really describe that day is to compare it to the day I had Mike Mike. Bringing him into the world was almost the same feeling as when he left here—a lot of people making noise and milling around, and my attention just glued to my new baby boy.

I’m not going to lie; I’ve been wanting to get mad and just go fuck the world up, because my son being killed has messed my whole life up. No way should my son have left here before me. But I have to stop myself every time my anger begins to build like that. If I look at it that way too long, I’ll find myself in trouble, doing something out of rage and revenge. That would be out of my character, and Mike Mike would never want me to do anything like that.

It’s so hard sometimes, but I have to find some type of something to keep myself calm so I can be a good wife and a good mother for my other kids. That’s why, looking at my son’s death today, I try to see it from more of a spiritual standpoint. God let me have Mike Mike for eighteen years. He wouldn’t let me have him longer because He had other plans for us. Those plans are still being revealed to me, but I believe a big part of His plan was to wake people up to some things in the world that need changing. I’m ready, though, for whatever He has in store.

What I do know for sure is that I was just a kid when I had Mike Mike. I made a lot of mistakes when I was young, but in raising him I got stronger, wiser. What we endured together, especially in his years as a small child, is a story that only his mother can tell. One that I have held close until now.

The naysayers and judgers and haters wrote me off when I had my baby, saying things like, “She ain’t gonna do nothin’ with her life,” but I never gave up. I had to develop thick skin to get through those scary and confusing days, but I was determined to make it for my child, to do right by Mike Mike.

I never finished high school. It was once one of the most uncomfortable and embarrassing facts about my life. Of course, I wanted my high school diploma. I even thought about going to college, but at the time, it was about providing and surviving—and I didn’t know how to do that and finish school. It was a hard choice, but life is hard sometimes, right?

I was raised in a single-parent house and watched my mother work hard on jobs she should have been paid more for doing, making sure my brother, me, and my sister had clothes on our backs and food on the table. I knew what her struggle had been.

I’ve worked for years barely making minimum wage, sometimes at two jobs, to put clothes on my children’s backs and shoes on their feet, even Mike Mike’s size 13 feet. I’ve even received public assistance, because a mother will put her pride to the side and accept help from others to make ends meet and care for her children.

As my firstborn, Mike Mike saw my struggles the most, and I know that motivated him to accomplish the dream I had of finishing school. Same for my other three kids who came after Mike Mike. I know they can go farther and do better than me and be successful in this life. So on May 23, 2014, when Mike Mike received his high school diploma, just a few months before he was gunned down, I was able to live my dream through him.

Every day is rough for me, but like Maya Angelou said, “Still I rise!” Amen! I find a way to smile because my baby had aspirations and dreams. That really gives me comfort on the low days. That’s why I got to clear things up, because folks out here got it twisted: Mike Mike wasn’t a criminal who deserved to be shot like a dangerous animal. He was a good boy who cared about the right things, and family and friends were at the top of his list. He didn’t have a police record. He never got in trouble. He was a techie, in love with computers. He loved his mama and was proud to be headed to college and of the things he knew. The whole family was proud of him, too.

When my son was killed, everybody had his or her own version of how everything went down. Cops with their version of the facts. People living in the Canfield Apartments with another. The television and newspaper people, EMTs, firemen, old people, young people, black, white, you name it—everyone with a different story that was supposed to be the truth about my son’s last minutes on earth.

My son was dead on the street in front of the world, and everybody except Mike Mike was busy telling his story. Even in the months since that horrible day, people still haven’t stopped talking, from Twitter to Facebook to Instagram, in the beauty shop and coffee shop, everywhere.

Well, let me just say this: I wasn’t there when Mike Mike was shot. I didn’t see him fall or take his last breath, but as his mother, I do know one thing better than anyone, and that’s how to tell my son’s story, and the journey we shared together as mother and son. So I’m about to give it to you.

This is the truth of it.

CHAPTER ONE

FOUR AND A HALF HOURS TOO LONG

The deli at Straub’s where I worked had been jumping since I got there. Straub’s is a kind of cozy gourmet market. It’s in a suburb called Clayton, where you got mini glass skyscrapers; little cafes with that chichi, froufrou food, you know those kind of restaurants where the menu be making basic stuff like a house salad sound like a foreign language; and boutiques that be selling a T-shirt for fifty dollars just because it’s got some high-end designer’s name on it, and I could go right over to Dots or Rainbow and get a shirt that look just as good for fifteen.

The county court was just down the block, so we got a lot of lawyers, judges, and businesspeople coming in to buy lunch. But we also got some of the regular, everyday folks that worked in the offices around there, like county clerks, DMV workers, secretaries, basically the people who do all the work for those high-paid people.

Then you had your white soccer moms and a lot of rich old white people who came in to do their weekly shopping. Mixed in, there are a handful of black professionals. I was so proud when I saw a brotha come up to my counter, representing with his Brooks Brothers suit on, showing them white folks that we had it going on too.

One of my best customers was Mrs. Hirschfield, a little Jewish lady who was real cool and always came directly to me. One day I saw her coming in the door and figured I’d make her my last customer before my break.

“Hi, my favorite customer!” I called out, giving her a warm smile.

“Good morning, Lezley! I just love you!” She smiled back. She was a petite woman in her sixties, a little homely, she wore large glasses, and her hair was curled and poufy.

A few of my coworkers rolled their eyes. Everybody said she was annoying, probably because she couldn’t always make up her mind about what she wanted, but I thought she was sweet.

The first time I met her, I was working one of the store’s private tasting parties upstairs. As I was roaming the room with my serving tray, I kept making eye contact with this plain-dressed woman. Each time I passed by with a reloaded tray, she eagerly tapped me and whispered, “Can I please have another?”

My coworker joked, “Damn, she asking for more?” I got a kick out of it. Hell, I encouraged her to take two and three at a time. Why not? They were free! To this day, Mrs. Hirschfield will sample the whole deli display if you let her. And I always do.

So, even though I was anxious to dip out, I didn’t mind squeezing her in at all.

“I’ll take some artichoke dip and a pint of chicken salad,” she said, smiling.

“No problem, I’ll have everything right up for you. You made it just in time before my break.”

“In that case, I’ll take a Lezley too!” She gave me a wink.

Customers be begging for a Lezley. That’s a sandwich they named after me. It isn’t anything but roast beef, but I guess it’s how I make it.

I laid out two pieces of soft wheat bread like I was about to perform surgery, smeared some brown mustard on, and gently placed the roast beef on it, sliced not too thick, not too thin. Then I laid the Swiss cheese on it, then topped it off with pickles, banana peppers, and onions.

To me that sandwich isn’t anything special, but like all the food I make—eggplant Parmesan, grilled artichoke, all that chichi, froufrou stuff we sell there, to good old down-home soul food—I make it with love. When you have a gift to “burn,” as my granny said, you can make any and everything.

I checked the time and quickly took my apron off before the stiff-looking man standing behind Mrs. Hirschfield could order. Break time! Before anybody could blink, I had slipped out and walked across the broiling parking lot to sit in my car, determined to make my few moments of peace matter.

I lit a cigarette, inhaled deep, and let my breath out slowly. Another hot-ass day in the Lou. I turned my key in the ignition and felt the whoosh of warm air from the car’s vents before the AC started to cool it down.

I took another puff from my cigarette, closed my eyes, and started to have one of them good old Calgon take-me-away moments. But right then my cell phone rang. Dang, so much for gettin’ a moment to myself.

“Hello,” I answered, half interested, letting out a cloud of smoke. I didn’t even look at the caller ID.

“Lezley, somebody been shot on Canfield, and he just laying here,” the man’s voice on the other end said in a panic. His voice was quivering and didn’t sound right.

I quickly straightened up. It was Mario, a coworker who lived in the Canfield Apartments in Ferguson, Missouri, a mostly black area in the suburbs a few miles away. That was the same complex my mother lived in. My son Mike Mike had been visiting her for the summer.

I took a nervous puff. “Mario, please describe him to me,” I said, beginning to shake all over. I took another puff and got out of the car, my hands trembling now.

“I’m trying to get near, but it’s so many people out here,” he said.

I swallowed, my mouth was all of a sudden dry, and I felt a dull thud fill my chest. It got faster and faster as I got out the car and began to pace the Straub’s parking lot, back and forth.

Just then my call-waiting clicked.

“Hold on! Hold on!” I shouted, trying to stay in control, but my hand holding the cigarette was now shaking uncontrollably.

“Nette . . . Nette Pooh!” It was my sister, Brittanie. Let me just say this: She isn’t really a frantic person. It’s like something could be bad, but she always stays calm. She’s the kind who holds it together enough to tell you what’s going on in a crisis. But her words were choppy, and she couldn’t get nothing else out before she broke down moaning and sobbing. It was weird she wasn’t screaming or nothing. Her crying was different than I’d ever heard it before.

Between her sobs, she was able to get out eight words: “Nette Pooh, the police just shot Mike Mike.”

I heard her, but my mind wasn’t trying to understand nothing like that. I quietly started gasping for air. What she had just said was trapped between my ears like some muddy standing water.

I didn’t ask her if he was still alive. I didn’t even want to think about that. A gust of wind sho...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Epigraph

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface: Mothers and Sons

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Epilogue: Mother to Son

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright