![]()

In recent years the image of the Third World in western minds has emerged in part from that of cataclysmic crisis – of famine and starvation, deprivation and war – to represent the opportunity for an exciting ‘new style’ holiday. Offering the attraction of environmental beauty and ecological and cultural diversity, travel to many Third World countries has been promoted, especially among the middle classes, as an opportunity for adventurous, ‘off-the-beaten-track’ holidays and as a means of preserving fragile, exotic and threatened landscapes and providing a culturally enhancing encounter. At the same time, many Third World governments have seized upon this new-found interest and have promoted tourism as an opportunity to earn much-needed foreign exchange – another attempt to break from the confines of ‘underdevelopment’.

There is something contradictory in viewing the Third World through an analysis of tourism. At one extreme there is the association of the Third World with fundamentalist terrorism, a risk to the security of the West, or overpopulation, poverty and disease. At the other there are also more subtle manipulations by the tourism industry of friendly and culturally diverse Third World peoples, natural and pristine environments and ecological variety. Both extremes, we will argue, form an important element in understanding contemporary Third World tourism. Importantly, and central to the line of argument developed in the following chapters, tourism is a way of representing the world to ourselves and to others. It cannot be understood as just a means of having some enjoyment and a break from the routine of every day, an entirely innocent affair with some unfortunate incidental impacts. Rather, a deeper understanding of tourism is needed to appreciate fully its content and expression as well as its potential impact.

Primarily, this is a book about development and its reflection in tourism; tourism is a metaphorical lens that helps bring aspects of development into sharper focus. It is not just about the role and impact of tourism in Third World development, but also about the roles of First World people and organisations (operators, tourists, non-governmental organisations, etc.) in the manufacture of ‘development’ as an idea, project or end state.

Purpose and limits of the book

This book focuses on new and purportedly sustainable forms of tourism to Third World destinations in the context of a world undergoing accelerated processes of globalisation. The focus is relatively tight in two important respects. First, there are now many studies of tourism, especially tourism in the Third World, that catalogue and discuss its growth and impacts. In particular, studies have tended to highlight the economic, environmental and sociocultural impacts of conventional package tourism.1 Rather than adding to this body of work, we focus particularly on the under-researched ‘new’ forms of tourism promoted in the First World and patronised mainly by North Americans, Europeans and Australasians (and with increasing participation of the middle classes in some Third World, so-called middle income countries that have rapidly industrialised and within which pockets of substantial wealth are concentrated). Although proportionately small relative to all forms of Third World tourism, the new forms of tourism are significant in terms of both the claims that are made about them and the rate at which they are growing.

Second, we do not seek to add to the growing number of accounts which attempt to identify sustainable tourism development (in terms of the environment, economy and culture) or prescribe good practice methods and tools for achieving this goal. Many of these have emerged from First World sources and necessarily involve judging the sustainability or otherwise of varying types of Third World tourism development. Instead, we explore the ways in which the claim, or discourse, of sustainability is used and applied to new forms of tourism (for example, the way in which ecotourism – a now not-so-new form of tourism – is premised upon the notion of sustainability). One way of capturing this important difference in our approach is to state that this is a book about sustainability and Third World tourism, rather than sustainable Third World tourism. The former approach, adopted here, signals the need for a critical analysis of the issues, while the latter implies the need to define and prescribe models of good practice.

Tourism as a multidisciplinary subject

Rather than commencing a study of Third World tourism with the environmental, economic and sociocultural impacts of tourism (worthy though these are as research considerations in themselves), the starting point here involves seeking to understand how sociocultural, economic and political processes operate on and through tourism. In other words, it is necessary to take a step back in the analysis of tourism. This stems in part from the weaknesses present in the tourism literature. As Britton observes:

Although over-simplifying, we could characterise the ‘geography of tourism’ as being primarily concerned with: the description of travel flows; microscale spatial structure and land use of tourist places and facilities; economic, social, cultural, and environmental impacts of tourist activity; impacts of tourism in third world countries; geographic patterns of recreation and leisure pastimes; and the planning implications of all these topics … These are vital elements of the study of travel and tourism. But these sections are dealt with in descriptive and weakly theorised ways.

(1991: 451)

This problem is of fundamental importance as it has led to an absence of an adequate theoretical critique for understanding the dynamics of tourism and the social activities it involves.

There are, therefore, two identifiable groups of tourism research. The first is concerned primarily with auditing, categorising, listing and grouping the outputs or consequences of tourism; the second approach is concerned primarily with conceptualising the forces which impact on tourism and, through an analysis of these forces, providing a broader context for understanding tourism. The crucial difference in the latter approach is that tourism is seen as a focal lens through which broader considerations can be taken into account, and it confirms the multidisciplinary foundation upon which tourism research is built; and it is in our opinion the only way in which tourism can be comprehended. As a personal activity, tourism is practised by a diverse range of the population; as an industry, it is multi-sectoral; and as a means of economic and cultural exchange, it has many facets and forms. Any comprehensive analysis of the field must therefore be multidisciplinary; and of necessity a study of tourism must be a net importer of ideas, themes and concepts from the broader social sciences.

Accordingly, our discussion draws on economics, development theory, environmental theory, social theory, politics, geography and international relations, for example. Inevitably, this breadth of consideration will mean that a number of relevant aspects are not examined in depth, and do not necessarily cover the complexity of the matters under discussion. We hope, however, that the discussion will serve as a stimulant to further thinking, discussion, research and study.

At the same time as using the concepts of a range of academic and intellectual fields in order better to understand tourism, the study of tourism helps us to illuminate more general economic, political, social, geographical and environmental processes. We try not to see tourism as a discrete field of study. Rather, it is an activity which helps us to understand the world.

Key themes and key words

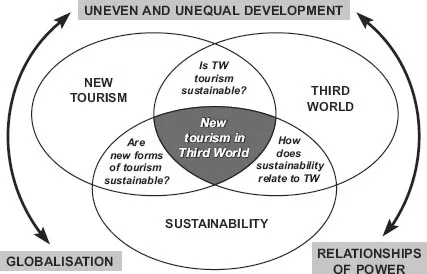

We have attempted to draw attention to the principal components of the discussion under the banners of key themes and key words. The relationships between the analysis and the key themes and key words are summarised diagrammatically in Figure 1.1. In reality these ideas are interconnected and dialectic; it is, therefore, principally a means of trying to organise our thoughts and approach. In very broad terms, these ideas respectively are shorthand for the rapid pace of global change and interdependence, an increasing global environmental awareness and a heightened concern with global inequalities and protracted structural poverty. The point we wish to emphasise is that such is the scale, nature and depth of the processes and problems assumed within globalisation, sustainability and development, three of the most significant drivers and reflectors of change, that they should therefore hold the centrepiece of our analysis. Chapter 2 is dedicated to analysing these formative ideas. Noteworthy here are the increasing concern and processes of change associated with each of these notions since the 1950s and of their accelerated significance since the 1980s – so much so that it is difficult to consider one without the other: sustainable development, global sustainability, global development, and so on.

Three themes seek to underpin the discussions throughout the book. The first, and most significant, theme is the uneven and unequal development which underlines the relationship especially between the First World and Third World (but also at inter- and intra-regional and intra-national levels), and through which we argue all forms of tourism are best understood. At its most basic level this theme is reflected in the fact that, for the time being (and notwithstanding the rapid growth of tourists generated from China and Russia in particular), it is still people from the First World who make up the significant bulk of international tourists and it is they who have the resources to make relatively expensive journeys for pleasure. Equally, processes of uneven development are reflected through the growing elite and newly wealthy classes in some Third World countries who are now able to participate in tourism. And of course tourism development is also highly uneven geographically. Areas that are in fashion today may fall from grace tomorrow.

Uneven and unequal development seeks to demonstrate why a critical understanding of tourism can be expanded through an analysis that places relationships of power, the second of the key themes, at the heart of the enquiry. These relationships range from the political, economic and military power of First World countries in contrast to Third World countries, the power wielded by international multilateral donors (from the World Bank to the European Union), the power of local elites in contrast to the local populations in tourist destination communities, and the power invested in tourists themselves. Our contention is that an analysis of tourism must start from an understanding and critical assessment of the relationships of power involved.

Figure 1.1 Key themes and key words

The final key theme is globalisation, a notion that at its core attempts to capture the idea that we are living in a shrinking world, a world in which places (countries, cities, communities, tourist resorts and so on) are increasingly interdependent.

In addition to these three themes which inform the analysis of Third World tourism, there are a number of key words which will recur throughout the book and which structure our discussion. As Figure 1.1 records these are sustainability, tourism and the Third World. The idea of a key word is used here because it alerts us to the fact that words are open to debate and differing interpretations; and that, consequently, there are problems in attaching uncontested meanings to words. As Williams (1988) suggests, the meanings of key words are closely related to the problems they seek to discuss. Take the idea of sustainability for example. The very many meanings and interpretations of this idea are often a direct reflection of the explicit and implicit connections that people make (Williams, 1988: 15). For environmentalists, for example, the problem is one of the degradation of the world’s natural resources that activities such as tourism have caused. And the meaning attached to sustainability in this case is, at its core, ecological: the need to preserve and protect the natural environment. To industrialists by contrast, sustainability may represent the opportunity to reduce costs, increase or retain market share, win new customers and increase profit margins. In the former, there is an assuredly ethical dimension associated with the sustenance of the environment for all; in the latter, a primary concern to protect and enhance shareholder interest. Arguments contesting sustainability have become more intense as the global tourism industry’s dependence on air travel has become clearer for all to see. Nowhere has the intensity of this contest been stronger than at the Rio + 20 Earth Summit (the UN Conference on Sustainable Development) held in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012. Here the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) launched its controversial ‘Sustainable aviation for generations to come’ initiative. The issues associated with the key word sustainability are explored in greater depth in the new Chapter 10 (Climate Change and New Tourism), although as a key word it permeates all our discussions throughout the book.

In the context of this book, tourism itself is, of course, the most obvious key word. For the purposes of this discussion, the term ‘new tourism’ has been adopted. While this is a rather broad term, it helps to indicate that a variety of tourisms have emerged and that in some important respects these seek to distinguish themselves from what is referred to as mainstream or conventional mass tourism – the type of tourism that has attracted the most academic attention and the wrath of many commentators. It will be argued later that the ‘new’ in tourism also helps us to trace the relationships with new types of consumer (known as the new middle classes), new types of political movements (ranging from new socio-environmental movements to the so-called anti-globalisation movements) and new forms of economic organisation (known as post-Fordism).

The meanings attached to tourism are many and varied, and ‘tourism’ and ‘tourist’ have in some quarters become derided and ridiculed. How often are people heard to describe their holidays as being ‘well away from tourists and the main tourism areas’? In other quarters, Third World tourism is regarded negatively, and the word symbolises a range of problems: environmental degradation, the distortion of national economies, the corruption of traditional cultures, and, on a trivial level for the individual, unsanitary conditions and food poisoning. The emergence of new forms of tourism (prefixed with sustainable and eco-, for example) is testimony to the identification of the problem and the attempt to signal that these new forms aim to overcome the problem and to be something that plain old ‘tourism’ is not.

The final key words are the geographical focus of the analysis, the so-called Third World. The history of development studies has thrown up a variety of terms that attempt to represent and categorise countries according to their wealth and social well-being. In particular, the terminology attached to countries lower down the ‘human development index’ (a widely adopted index ranking countries on a number of criteria) has been keenly disputed – should they be described as ‘poorer’, ‘lower income’, ‘developing’, ‘under-developed’, ‘the South’, ‘Third World’, or indeed ‘non-viable economies’ (de Rivero, 2001) or ‘slow economies’ (Toffler, quoted in Sachs, 1999)? All such terms possess their advocates and detractors, reflect political priorities and dispositions, and no one term will suit all audiences. The problem of definition is made more acute when rapidly changing economic factors mean that old categories no longer hold good, and the meaning of development is constantly contested (Nederveen Pieterse, 2001).

Principally, in this book, we refer to Third World and First World as general shorthand (and a generalisation) for the spatial and socio-economic inequality and unevenness between and within regions, countries, and cities: an expression of contrast for example between inclusion and exclusion, the empowered and disempowered, the haves and have-nots. Other terminology is used only where direct quotes from other sources necessitate this or where the meaning conveyed by the alternative term is distinctly different from these two terms (for example, in a differentiation between those relatively wealthy countries with significant new middle classes with a taste for new forms of tourism and those countries where the middle classes are currently demanding conventional forms of tourism, especially those in South Asia and the Pacific Rim). Occasionally, we also refer to the West and the Rest, where the ‘West’ represents the First World advanced capitalist economies promoting western materialistic lifestyles; and the ‘Rest’ seeks to emphasise the inherent inequality in global development.

‘Third World’ also helps to reflect on and convey the way in which we are using this term in relationship to the notion of development. For example, the word ‘developing’ is avoided, because it implies that there is an end state to the process of development and that all countries will eventually reach a ‘developed’ state. By contrast, there are strong grounds for arguing that the process of development is one which actually causes underdevelopment elsewhere and at the very least is a state of never-...