Literacy development broadly depends upon interactions among that which the child brings to the task of reading and writing, the script/language to be learned, and the environment in which this development occurs. Individual and age-related variability across children has been studied extensively in the reading (and writing) literature. Such variability is highlighted throughout this book, as typically developing and disabled readers, younger and older readers, and monolingual and multilingual readers and writers are broadly compared and contrasted. However, what children are reading and writing and how they are learning to read and write are equally crucial facets of literacy acquisition. In this text, literacy development is roughly and imperfectly defined as reading and writing development.

It is likely that there exist both universals and specifics of literacy development. At some level, the task of every reader/writer is to map oral language onto its written form. This process is, crudely, a universal. Reading and writing specifics depend upon the literacy environment, the language, and the script. (Please note that, throughout this text, the terms script, orthography, and writing system are used interchangeably. They are all taken to mean the way in which the language is represented in writing, including different alphabets or other types of print (e.g. Chinese characters, diacritics/accent marks, spellings with various alphabets, etc.).

There are numerous variations on literacy development, from American monolingual children learning to read a single script, to Swiss schoolchildren learning to read several Indo-European languages, to Berber-speaking Moroccan children learning to read a formal version of Arabic in the Quran. The specificity of these situations is overwhelming for one neat theory of literacy development. Research studies contrasting different situations in which literacy acquisition takes place are also limited; some of these are outlined below.

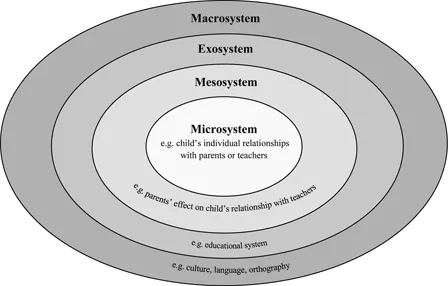

Understanding children’s literacy development first requires a conceptualization of various environments in which children acquire it. These environments involve many institutions, places, and people whose effects on how children learn to read and write are strongly linked. Such environments differ greatly from culture to culture, from city to city, from one child to the next. Bronfenbrenner (1979) articulated what developmental psychologists understand by the term environment. His ecological systems, which are useful for understanding various levels of environment affecting children’s literacy acquisition, are reviewed later in this chapter. Conceptualizing how environment affects literacy acquisition is particularly important in a book like this, which attempts to understand how literacy develops across cultures.

In direct contrast to this goal of learning about literacy development across cultures, the majority of research studies on children’s reading and writing development are focused squarely on the process of learning to read and, to a lesser extent, to write English within an English/western environment. Because this book is a review of relevant research on the development of literacy, it therefore follows that the majority of the research reviewed here will be on how and in what context children learn to read and to write in English.

This, of course, presents a big problem for those interested in understanding how literacy develops across orthographies, languages, and cultures, because English is quite peculiar in some ways (Share, 2008). For example, English is a culturally prestigious language with a history of domination (Baker & Jones, 1998). Learning to read and write in English as a second language brings with it other issues of language learning, such as unfamiliarity with the cultural values of monolingual English speakers, which may differ from native speakers’ focuses on reading skills. In addition, English is an irregular orthography, much less clear in its mapping of letters to sounds than are some other fairly common alphabetic orthographies, such as German, Portuguese, or Spanish (Share, 2008). The English script also differs greatly from various non-alphabetic orthographies such as Japanese or Chinese in ways considered explicitly later in this and subsequent chapters.

Although this chapter begins by considering literacy acquisition from the perspective of learning to read English, one purpose of this text is to stimulate discussion and research on the mechanisms by which children learn to read in different cultures and orthographies. I am hopeful that the research presented in the following chapters will arouse your interest in how and where children learn to read and write across the world, both in their native language and in second, third, or fourth languages, whether or not any of these happen to be English.

This book focuses on ten themes of reading and writing acquisition that are applicable across cultures. In this first chapter, we consider the effects of different environmental factors on literacy development. Chapter 2 then focuses on one of the well-researched areas of literacy acquisition: phonological (speech sound) development, from birth onwards. Here, the text covers the developmental aspects of speech perception, phonological sensitivity and awareness, including both segmental and suprasegmental sensitivity, rapid automatized naming, verbal memory, and language learning as they apply to reading acquisition. Chapter 3, ‘Building blocks of reading’, considers the importance of and extent to which three aspects of children’s beginning to read are applicable across cultures. These literacy acquisition fundamentals include home literacy environment, print components (e.g. Roman or other alphabets or Chinese semantic and phonetic radicals, as well as the extent to which the word as a unit makes sense for literacy development understanding cross-culturally), and print automatization.

In contrast to the broader themes of the first three chapters, Chapters 4 and 5 focus exclusively on particular cognitive skills for reading development. Chapter 4, ‘The role of morphological awareness in learning to read and to write (spell)’, explores the unique contributions of morphemes, or meaning units, to word/character recognition and writing, vocabulary knowledge, and reading comprehension. Chapter 5 highlights the development of visual and orthographic abilities for literacy acquisition across cultures.

Chapter 6 addresses the concept of specific reading disability, or dyslexia. This section covers the cognitive deficits associated with reading problems and the neuroanatomical markers of dyslexia. It also explores approaches to remediation of reading difficulties. Chapter 7 reviews research on reading comprehension in children. This review consists of a broad conceptualization of reading comprehension and then a consideration of motivation and some important cognitive constructs that contribute to its development. Chapter 8 shifts primarily to writing, by reviewing two diverse areas of research – spelling development and composition writing. Models of both are considered. We also briefly consider the issue of dysgraphia, a specific writing difficulty, as a parallel to dyslexia.

Chapter 9 focuses on the ways in which teaching affects children’s literacy acquisition. This section reviews the effects of school instruction on literacy, compares whole language and phonics approaches to reading, and explores how particular cognitive skills are influenced by literacy instruction. We also briefly consider the importance of electronic aids, such as computer programs and e-books, in facilitating literacy acquisition. Finally, Chapter 10 focuses on two areas of research into bilingualism and biliteracy. The first is on the transferability of cognitive skills, including phonological and orthographic processing, across languages to print. The second is on reading comprehension in bilinguals. We consider the question of whether it is possible to have reading difficulties in one orthography and not another for those who can read in more than one script or language.

As much as possible, and across the chapters, research on learning to read and to write in orthographies other than English is presented to offer a contrast with research on learning to read English. However, this chapter begins with an explicit consideration of issues related to reading English.

Environmental influences on literacy development in English

Perspectives from different researchers make clear that there are numerous environmental factors affecting how children acquire basic literacy skills in English. Among the most prominent of these include issues of home language spoken (Tabors & Snow, 2001), classroom teaching style (Chall, 1996; Foorman, Francis, Fletcher, Schatschneider, & Mehta, 1998; Treiman, Stothard, & Snowling, 2012), home environment (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998), and socio-economic status (Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998; Vernon-Feagans, 1996). Beyond the United States, across English-reading countries, additional variables related to English literacy development extend to dialect (Burk, Pflaum, & Knafle, 1982; Kemp, 2009; Terry, 2006; Treiman & Barry, 2000), how alphabet knowledge is taught (e.g. Connelly, Johnston, & Thompson, 1999; Seymour & Elder, 1986; Treiman, 2006), when reading-related skills are taught (Clay, 1998), and culture (Campbell,1998; Clay, 1998).

Although literacy development is important for most of the information we glean from childhood through adulthood, throughout this book my primary emphasis is on the early years of literacy development, which include emergent literacy, defined as the ‘developmental precursors of formal reading’ (Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998, p. 12) in children. I have always been particularly fascinated by the transition from a child not knowing how to read to being able to recognize some words in her world. The development of early literacy involves different systems, which interact in complex ways, as discussed below.

Literacy development contrasts: a comparison of Hong Kong Chinese and American monolingual English readers

To illustrate this point, let us consider an issue related to literacy development that I have struggled with in my own research: what are the similarities and differences in comparing reading development across Hong Kong Chinese children, who are learning to read English as a second orthography/language, and American monolingual English-speaking children? These children attend school in very different places, which means that, at the same chronological age, their knowledge of reading and writing varies markedly.

I ask this particular question for several reasons. Practically speaking, it is of interest because I have lived for extensive periods of time in both Hong Kong and the United States. Because my main research area of interest is literacy development, a Hong Kong–American comparison is an obvious one for me personally. Theoretically, this contrast is also of interest because the children from these two regions have such different early literacy experiences (Kail, McBride-Chang, Ferrer, Cho, & Shu, 2013; McBride-Chang & Kail, 2002). This contrast is introduced here to illustrate some striking differences in how children learn to read English across the world. This illustration is intended to focus attention on the fact that, although much has been written about how children learn to read and to write English, the meaning of this achievement cannot be understood outside of that cultural context. Obviously, the greatest contrast of all is in learning to read and to write English as a non-native versus monolingual English speaker. Yet along with this overwhelming difference follow a host of other, more subtle differences as well.

Typical Hong Kong Chinese children begin learning to read Chinese characters at the age of 3.5 years. They verbally label these characters using Cantonese, their native language. At the same time, they are learning to speak another language, Putonghua (translated in Chinese as ‘the common language’, and typically referred to by westerners as Mandarin), the dominant/governmental language spoken in China. As they progress through school, their literacy development will focus on learning to read using the grammatical structure and vocabulary of Putonghua, which sometimes differs from the native Cantonese. Along with these language and reading challenges, they also learn to read, write, and speak English at the same age, that is, beginning at 3.5 years old. Both Chinese characters and English words are learned in part via copying of each over and over again several times. Often, English vocabulary is acquired in its oral and written form simultaneously, as regularly occurs for learners of second languages. Reading of both Chinese characters and English words is often accomplished using the ‘look and say’ method, in which the teacher points to the written referent and pronounces it, after which the children are supposed to repeat the pronunciation. No phonological coding system is introduced to help children learn to decode for Cantonese literacy. In some schools in Hong Kong, letter sounds are still not taught. In many schools, phonics is not taught for English, partly because teachers still are not well versed in phonics; they themselves learned to read English solely via a look and say method. By the age of five, these Hong Kong Chinese children are often one to two years ahead in English reading-related skills, such as letter name knowledge and English word recognition, compared to their American counterparts.

In contrast, most American children are not formally taught to read and write until grade 1, when they are about six years old. Most learn to read English only. Furthermore, the large monolingual English-speaking population in America brings with it a solid oral vocabulary onto which these children can map the single orthography they are taught to read in school. English reading is taught in a variety of ways in the United States, but, typically, children learn some phonics, such as letter sound knowledge and how to put sounds together to form words, in this endeavour. Parental attitudes in America, as compared to those in Hong Kong, differ about the value of education and how best to accomplish the goal of literacy, particularly in their emphases on the relative importance of education and natural ability versus effort (as discussed below). Thus, from a cross-cultural perspective, the number and variety of factors that contribute to children’s literacy development are daunting.

Of course, this characterization of what is ‘typical’ in Hong Kong and American cultures is vastly oversimplified. Within the same city or town, aspects of individual children’s backgrounds, including the socio-economic status of the family, the educational background of the parents, the extent to which education is valued in the family, the parents’ parenting styles, and children’s own pre-literacy experiences, may differ dramatically. Since the first edition of this book came out, many more schools are teaching using Mandarin, rather than Cantonese, as the medium of instruction in Hong Kong. Across the world, conceptualizing literacy development becomes even more complicated, as educational policies and cultural expectations for a literate child are incorporated into a framework for explaining children’s literacy development. Culture, language(s) and orthography(ies) to be learned in order to attain literacy, governmental policies on education, parental backgrounds, and attitudes in any given place are all important for understanding literacy development. The remaining sections of this chapter will focus on some of the issues touched on by the Hong Kong–American illustration above, and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach (see Figure 1.1) is used as a model of the environmental factors affecting children’s reading acquisition.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach as applied to literacy development

Bronfenbrenner (1979) conceptualized environment as being comprised of at least four systems that interact. These interact within another dimension, which is historical period, or time. At the macrosystem level are cultural expectations of achievement, and language(s) and orthography(ies) to be learned. For example, Hong Kong Chinese children live in a society in which there is strong pressure to succeed academically. They also learn to map the traditional Chinese script (taught in Hong Kong and Taiwan, but not in mainland China or Singapore, where simplified characters are used) onto their native Cantonese language. In Hong Kong (but not in other Chinese societies), children are taught both Chinese and English word reading and word writing from age 3.5.

Tibi and McLeod (2014) noted that the macrosystem within the environment of the United Arab Emirates offers many idiosyncrasies that may affect children’s literacy development there as well. For example, the language that they learn to read first is Arabic. They learn to read in Standard Arabic, but the form of formal written, or Standard Arabic is different from the language they speak at home with their families. This phenomenon is known as diglossia. In such cases, there is a ‘high’, or formal, version of the language and also a more colloquial version of the language used for daily life. This occurs for Chinese and sometimes for German as well (e.g. Swiss vs ‘high’ German in German-speaking Switzerland), among others.

In the United Arab Emirates, there are many different forms of spoken Arabic, and these differ across tribes and families. In addition, many children in the United Arab Emirates are cared for partly by service workers who share different native languages, such as those from the Philippines or Indonesia. These caregivers use different languages to com...