![]()

1

What Is Formative Assessment?

Formative assessment drives mathematics instruction and is a key component in Response to Intervention. It is the process in which evidence of students’ understanding is used by teachers to adjust instructional practice (Popham, 2008). As practitioners, we routinely monitor student performance on specific outcomes and standards. Formative assessments are employed to measure student performance so as to provide a targeted instructional response. Monitoring student learning through formative assessments provides a gauge, pinpointing where students are on the pathway of acquiring new knowledge. Their performance on these assessments provides work samples to analyze. The samples enable us to see where students are in comparison to where they need to be to meet the standard. Only through this process, are we equipped to provide an effective and meaningful instructional response. Without formative assessment, lesson planning is focused solely on curriculum with little regard for students’ explicit academic needs.

How Does Formative Assessment Impact Student Achievement?

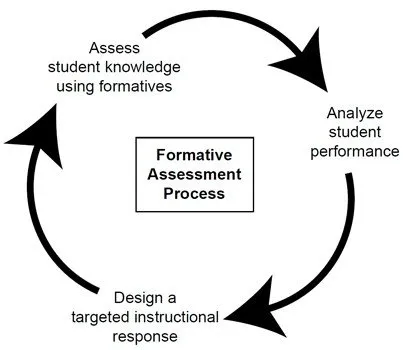

Effective formative assessment occurs simultaneously with instruction for the purpose of improving students’ knowledge and performance in mathematics. When formative assessment is implemented properly, students learn what is being taught to a substantially greater degree (Black & Wiliam, 1998). When we provide feedback to students as a result of formative assessment, it is the most powerful factor in enhancing student achievement (Hattie & Jaeger, 1998). The National Mathematics Advisory Panel (2008) recommends regular use of formative assessment so that instruction can be adapted based on student progress. “Teachers’ regular use of formative assessment improves their students’ learning, especially if teachers have additional guidance on using the assessment to design and individualize instruction” (2008, p. xxiii). This book provides such guidance for teachers through a three-phase format of assessment, analysis, and response as illustrated below.

As practitioners, we experience tremendous pressure to “cover” the curriculum in a timely manner. Unfortunately, this sometimes translates to a practice of teaching curriculum rather than teaching children. Teaching and learning form a dynamic alliance that is reliant on the interactions between teachers and students. These interactions serve as feedback to teachers and inform next steps for instruction designed to advance learning. In order to efficiently and effectively teach children, we must understand what they already know in order to plan meaningful next steps.

We have heard teachers lament about this process and become overwhelmed at the prospect of providing differentiated instruction for individual students. Advocating an individualized instructional program is neither realistic nor appropriate for most classroom teachers. All students are entitled to instruction designed to meet their identified needs, but this does not have to translate into a one-on-one instructional setting. Students can be grouped according to similar instructional needs. When analyzing student understanding of a math concept for an entire class, patterns and trends emerge and students’ needs are often revealed in clusters. There may be times when we need to work with an individual student to reteach a concept or clear up a misconception; however, often there is a small group of students for whom the data show similar academic needs.

How Is This Book Organized?

Using Formative Assessment to Drive Mathematics Instruction in Grades 3–5 contains seven chapters. The first chapter identifies the purpose and intentions of this book by describing formative assessment and highlighting the impact of the process on student performance. Chapters 2 through 6 outline a process for the use of formative assessment to inform instruction. Each of these chapters addresses one of five content standards in mathematics: number and operations; algebraic thinking; geometry; measurement; and data analysis and probability. Within each content standard, key mathematics concepts are highlighted. These concepts were identified from such sources as the Principles and Standards of School Mathematics (NCTM, 2000), the Curriculum Focal Points for Prekindergarten through Grade 8 Mathematics (NCTM, 2006), and the Common Core State Standards Initiative (2010). The concepts directly addressing the Common Core State Standards are labeled as such in the table of contents with this symbol CCSS. Other concepts serve as foundations for later CCSS. Chapter 7 is a brief conclusion with final comments of the formative assessment process.

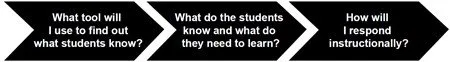

The formative assessment process in Chapters 2 through 6 is presented in a three-page format for each highlighted skill or concept. Each of the three pages is designed to answer the following questions regarding student performance and mathematics instruction:

The formative assessments, student work samples, and suggested activities are provided for each mathematics concept to help teachers respond to these questions when planning instruction. Each is a deliberate step toward implementing effective mathematics instruction.

The first page in the three-page design illustrates a common sample of a Traditional Formative Assessment that one might find in a textbook or teacher resource (see Figure 1). Just below the assessment item is a Limitations note cautioning potential shortcomings of the traditional assessment. The Traditional Formative Assessment is then followed by a suggested Enhanced Formative Assessment, which is provided as an alternative to the traditional format. The Enhanced Formative Assessment is designed to elicit responses offering more insight into student understanding and remedy the limitations associated with the traditional assessment.

The second page in the three-page format includes four student responses to the enhanced formative assessment from the previous page (see Figure 2). The student responses are sequenced according to level of performance, beginning with a low level of understanding and ending with a high level of understanding for each concept. The first student work sample (Ulma) demonstrates minimal understanding. The second and third student samples (Vernon and Wayne) demonstrate moderate understanding, but with varying degrees of success. The final work sample (Yohanna) represents complete understanding of the assessed content. The shaded box just below each sample offers an analysis of the student work and guides the reader to the appropriate Instructional Focus provided on the next page.

Although the instructional focus was developed with an individual student’s response in mind, this is not to suggest that a teacher should develop or provide a different task for each student. It is not practical to expect teachers to implement individualized lessons. The student samples help to identify a level of understanding in which several students may fall. The task is intended to address the needs of students with similar understanding whom are working at a compatible level. The activities are designed to facilitate discourse among students in a small group setting.

The format of the third page includes four small group Focus Activities (see Figure 3). Each of the Suggested Activities is designed as a strategic response for students with instructional needs revealed in the work samples. The small group Rebuild Focus is designed for students demonstrating minimal understanding. The activity introduces the key concepts through an interactive task and provides an opportunity to acquire new knowledge. The small-group Core 1 Focus and small-group Core 2 Focus activities are geared for students with moderate levels of understanding. Although both Core Focus tasks target students with some understanding of the concept, each activity carries a different and specific focus based on the interpretation of needs from the student work samples. The Core 1 Focus activity is a slightly lower level of complexity than the Core 2 Focus activity. Lastly, the small-group Challenge Focus activity offers an enrichment opportunity for students demonstrating complete understanding of the math concept.

Each small-group Focus Activity is formatted with a defined goal, a list of needed materials, a description and directions for the task, and potential questions to pose while students are engaged in the activity. Response to Intervention calls on teachers to provide effective and meaningful instruction. This resource provides a means to that end by serving as a guide for identifying students’ needs and responding accordingly.

How Can These Resources Be Utilized Effectively?

This book is designed to provide math educators with tools and resources targeting the varying needs of their students within five content standards of mathematics. When teaching a new concept or skill, students demonstrate a diverse range of competencies. A teacher introducing a lesson on fractions, for example, must simultaneously consider those students who are uncertain what a fraction represents, as well as those possessing a strong sense of fractions and are ready to tackle complex problems. The three-phase approach of this book assists teachers in identifying what students already know about the specific concept, facilitates meaningful student groupings according to current levels of understanding, and provides hands-on activities for instruction at four varying levels. It is not the intent of the authors that all students complete all four activities. Rather, the teacher may choose those activities most appropriate for groups of students.

Even though the activities are designed to be an appropriate and targeted response to the identified needs of a student, some students may need to engage in more than one of the provided activities. The sequence of task difficulty suggests that students beginning at the Rebuild Focus level may well benefit from working through the Core 1 and Core 2 tasks as well, in order to meet the standard of performance measured in the Enhanced Formative Assessment. Additionally, the four activities...