1.1 Overview

International trends are demonstrating that concepts and tools such as design for environment (DfE), life-cycle assessment (LCA) and extended producer responsibility (EPR) are here to stay. They are rapidly becoming key tools for forward-thinking corporations. Furthermore, a growing body of evidence suggests that such approaches are exceptionally well placed to deliver a range of benefits over and above environmental benefits and mere compliance. These ‘new millennium’ tools will revolutionise how business creates new products and services and how consumers and government will compare, assess, regulate and purchase everyday goods.

In particular, DfE provides a unique opportunity to make critical interventions early in the product development process and eliminate, avoid or reduce downstream environmental impacts. What will emerge as a continuing thread throughout this book is that DfE is a technical and creative ‘key’—a device that can substantially determine how a product is likely to interact with the environment and its users. In other words, DfE can make considerable environmental and commercial gains based on the basic philosophy that ‘prevention is better than cure’.

1.1.1 Environmental improvement: why focus on design?

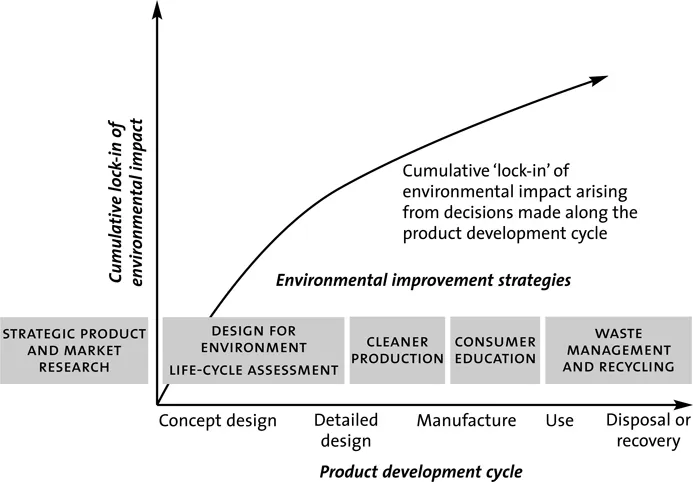

Environmental impacts occur at all stages of a product’s life-cycle. Different types of products have impacts at different stages of the life-cycle. For example, for furniture the raw materials and final disposal embody most of the environmental impacts, and for energy-consuming products such as household appliances the use of the product embodies most of the environmental impact. However, no matter where in the product life-cycle the impact lies, most of the impact is ‘locked’ into the product at the design stage when materials are selected and product performance is largely determined. This concept is represented in Figure 1.1, along with the types of strategy used to address environmental performance along a product development cycle.

Figure 1.1 Conceptual representation of environmental ‘lock-in’ over a product’s development cycle

At a very practical level, DfE, accompanied by a judicious use of LCA, provides one of the most powerful tools in pursuit of sustainable products. It is at the product planning and design stage that waste avoidance, source reduction, water conservation and energy efficiency can be locked into products, services and buildings. Trying to implement such strategies once the design is resolved or settled generally reflects an ‘end-of-pipe’ orientation and represents ‘yesterday’s thinking’.

What becomes apparent—whether one is considering a domestic appliance, food packaging, office furniture or textiles—is that only a life-cycle design approach can lock in positive environmental features and lock out undesirable environmental impacts. At a policy level, it is a genuine product stewardship approach that embodies the principles of EPR, with brand-owners taking much greater responsibility for their products when they are discarded.

The overarching significance of DfE is further reinforced by the expanding list of companies allocating substantial resources to sustainable product development. Their creation of environmentally improved products is not only testament to serious corporate environmental foresight but also an acute reminder that the sceptics have got it wrong. Regardless of the goods produced, DfE is becoming a key strategy motivating many of today’s companies, including Philips Electronics, Hewlett-Packard, Interface, Wilkhahn, Herman Miller, Miele, Electrolux, Xerox, BMW and Daimler-Benz—to name but a few.

On the subject of companies, methods and sustainability in isolation of people can only go so far. Good design, sustainable design, commercially successful design requires smart thinkers, enthusiastic individuals, committed teams and progressive executives (i.e. innovative eco-product developers).

1.2 Critical players: the role of designers and product developers

It becomes vividly apparent that those professions and trades involved in designing new products are key players in helping realise a more sustainable future. Whether it is the formally trained industrial designer, engineer, model-maker, marketing manager, psychologist, technical writer, toolmaker or plastics specialist—we need to recognise that many areas of knowledge work together and toward the development of environmentally preferable products. In many ways it is more accurate to talk about eco-product developers rather than of ecodesigners.

Working alone, the designer’s environmental role is limited; in combination with other disciplines, the designer emerges as a critical player in ensuring that a diverse and sometimes conflicting range of issues and considerations are successfully built into a product. It is ultimately the designer who creates the interface between the consumer and the technology underlying the shell or surface of a manufactured product. Thus the designer’s ability to play the role of environmental champion is unequalled compared with others.

An interdisciplinary approach is not only an essential requirement of successful DfE but also a highly desirable approach if we want to maximise the commercial and environmental performance of a manufactured product. Collaboration facilitated by a genuine enthusiasm to learn, share, evolve, explore, innovate, discover and apply environmental qualities is likely to result in the rethinking and reconfiguring of the product development process on all fronts, not just the environmental front.

We simply need to look around us, wherever we are, and note the almost infinite extent to which designers shape our physical and virtual worlds. It is ultimately the designer who gives form and meaning to objects that not only offer utility, function and convenience but also entertainment, desire and visual pleasure. However, although a growing number of designers are openly acknowledging that they wish to be part of the solution that is sustainable development, many designers and others involved in product development seem to feel paralysed or restrained from having a positive or significant environmental effect on the design process.

Recognising that the designer or the product development team can take practical action to shape, fashion and model ideas and concepts into sustainable products, it must also be acknowledged that the goal is not to transform designers into environmental scientists. It is about blending environmental considerations into the roles of all in the product development team—be they designers, engineers, psychologists, marketers, toolmakers or executives. Above all, designers and product developers need to throw off their shackles and forge ahead on implementing DfE. They must start small, make no-risk or low-risk decisions, establish ‘environmental’ dialogue with suppliers and other stakeholders and, most of all, remember there are probably many common-sense design decisions that they have already been making that equate with DfE. Although some academics emphasise complex methodologies that may blur and burden DfE, the reality is that many significant environmental improvements can be realised through the use of basic checklists and general rules of thumb.

In other words, you do not need to be a rocket scientist to successfully implement DfE strategies within a commercial context. Understanding the jargon and terminology may help, though.

1.3 What’s in a name? Some definitions

Accurate descriptors or buzzwords? What is design for environment and where does it sit on the spectrum of other terms related to environmentally oriented product design? Is it different from green design, ecodesign and sustainable design?

The answer to these questions depends on who you ask; however, the ultimate goal or end-point associated with such terms remains similar: that is, designing products as though the environment matters, and minimising their direct and indirect environmental impacts at every possible opportunity.

In essence, whether the process is referred to as DfE or ecodesign, the fundamental objective is to design products with the environment in mind and to assume some responsibility for the product’s environmental consequences as they relate to specific decisions and actions executed during the design process. Obviously, the designer cannot bear responsibility for all negative effects; however, the designer can have a significant influence over the environmental impacts that may arise upstream and downstream of his or her own interaction.

A robust DfE approach is one that blends creative excellence, innovation and technical rigour with a view to fearlessly pursuing major environmental and functional objectives. Ultimately, products have a function and a purpose, and this must remain the designer’s priority. The challenge is to assert product functionality while simultaneously minimising life-cycle environmental impacts and maximising competitiveness.

One of the critical adjuncts to DfE over the past decade has been incorporation of LCA, sometimes more popularly referred to as cradle-to-grave analysis. LCA is one of the most useful tools in identifying and assessing the environmental aspects and potential impacts associated with a product. The value of LCA is in its ability to map a product’s environmental impact across its whole life-cycle, including:

- Extraction and processing of raw materials

- Manufacture of the product (and any associated packaging and consumables)

- Use or operation of product

- End-of-life options (e.g. re-use, remanufacture, recycling, treatment and disposal)

A critical distribution or transport phase usually occurs between all the above stages and can have a significant impact on a product’s life-cycle environmental impacts.

It is this life-cycle perspective that has formed the cornerstone of DfE and won the support and acknowledgement of progressive governments and corporations, of the global environment movement and of an ever-growing list of influential designers. In design terms, LCA can perform practical functions as well as more strategic tasks.

Use of LCA as a DfE tool can:

- Benchmark the environmental performance of existing products

- Develop environmental targets for the product development team to pursue

- Provide a ‘work-in-progress’ assessment tool to review how a concept or detailed design might perform environmentally

- Help the product development team make decisions regarding materials and components

- Identify previously unknown impacts associated with a product and associated consumables

The collective outcome of using LCA to provide the above data can inform and direct the design process like no other environmental management tool. Despite its practical value and unique product profiling qualities, LCA does have its limitations and constraints. Poor quality of input data, questionable assumptions, sloppy methodologies and debatable interpretation can all undermine or ‘contaminate’ LCA. However, when ethically and rigorously utilised, it can significantly enhance the potency of DfE. For more detail on specific LCA strategies and tools, see Chapter 3.

When defined and applied strictly, approaches such as sustainable design or sustainable product development begin to deviate from the way most designers perceive and apply DfE. Sustainable design begins to address the bigger picture by considering collectively some of the harder questions, such as need, equity, ethics, social impact and total resource efficiency and thus the role of design in achieving inter-generational equity. More specifically, sustainable design seeks to translate and embody global and regional socio-environmental concerns into products and services at the local level. This necessarily demands a systems view of design and does not always focus on realising physical products.

Buzzwords often associated with sustainable design include dematerialisation, product-to-service strategies,‘Factor 4’ and ‘Factor 20’ goals as well as backcasting and other modelling tools (see also Box 1.1). The aim is to minimise incremental ‘tinkering’ through end-of-pipe environmental management, cleaner production and DfE, and to maximise robust system-wide solutions in pursuit of more sustainable modes of production and consumption. This is discussed further in Chapter 10.

When a designer is immersed in the design process, trying to meet a client’s expectations and to satisfy consumer desires, terminology can become peripheral. What is obvious and central to the task is that DfE is an approach concerned with delivering meaningful environmental benefits, possible only through mainstreaming environmental concerns and realising low-impact products that are culturally relevant, economically viable, technically innovative and ecologically compatible.

Box 1.1 A palette of buzzwords

THE FOLLOWING IS A PALETTE OF TERMS THAT IN SOME WAY DEFINE OR REFER TO environmentally sensitive product design.

- Design for environment

- Ecological design

- Environmental design

- Environmentally oriented design

- Ecologically oriented design

- Environmentally responsible design

- Socially responsible design

- Sustainable product design

- Sustainable product development

- Green design

- Life-cycle design

- Dematerialisation

- Eco-efficiency

- Biodesign

No doubt the list will grow as the area develops.