![]()

1.1 Our climate is at stake

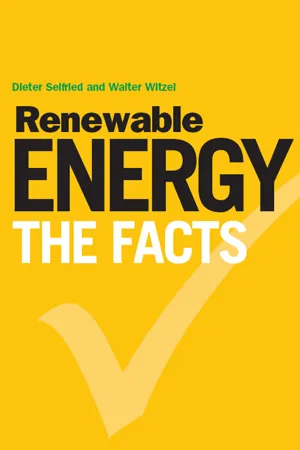

Climate change is already making itself felt. Over the last century, the average global temperature rose by 0.7°C. Glaciers in the Alps are retreating, as is the Arctic ice shelf. The frequency and strength of hurricanes has increased, and extreme weather events – such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the heatwave in Europe in 2003 – are becoming more common.

The causes are well known. When fossil energy is burned, carbon dioxide (CO2) is released. Its concentration is increasing in the atmosphere, strengthening the greenhouse effect. Since the pre-industrial age, the concentration of CO2, the most important heat-trapping gas, has risen from roughly 280 parts per million (ppm) to the current level of almost 390ppm. But CO2 is not the only heat-trapping gas emitted by civilization. For example, large amounts of methane are released by farm animals and in coal and natural gas extraction. Likewise, laughing gas (nitrous oxide, N2O) is a heat-trapping gas from agricultural fertilizers.

These gases change the amount of energy trapped in the atmosphere and the amount reflected back into space. Shortwave sunlight penetrates the atmosphere and is reflected from the Earth's surface. Reflected waves are generally longer and cannot penetrate the atmosphere as well; heat-trapping gases partially absorb them. This natural phenomenon (the greenhouse effect) is vital for our planet; without this effect, the Earth would have an average temperature of –18°C. The increasing concentration of these heat-trapping gases is gradually disturbing this ecological equilibrium. Land and oceans are heating up faster, more water vapour evaporates from the seas, and hurricanes and typhoons are becoming more common. The overall amount of energy input into the atmosphere is increasing. As a result, extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and heatwaves are becoming more common.

A decade ago, the idea that climate change was man-made was still controversial, but today there is a widespread consensus: ‘Nowadays, no serious scientific publication disputes the threat that emissions of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels poses to the climate’, says Professor Mojib Latif from the Leibniz Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of Kiel, Germany.1

Nonetheless, there is still some resistance to efficient climate protection policy, though this opposition is not the result of honest doubts about climate change. Rather, some industrial sectors simply have an eye on their bottom line and are concerned that their profits may suffer, as some countries and lobby groups would have us believe.

Figure 1.1 Our climate is at stake

Source: Al Gore, An Inconvenient Truth, 2006; BMU

1.2 The inevitable fight for limited oil reserves

At the beginning of the 1970s, the Club of Rome's Limits to Growth raised awareness about the idea that exponential growth on Earth is not possible in the long term. It also stated that crude oil reserves would be depleted in 30 years under a specific set of assumptions. Today, oil reserves are reported to be 1200 billion barrels (a barrel contains 159 litres), and the statistical range is reported as 42 years.2 Those may sound like reassuring figures, but they are not. And there are several reasons why.

Statistical range is an indication of how many years current reserves – economically extractable oil using current technology and assuming that consumption remains constant – will last. But of course, if oil consumption continues to increase as in the past, then the statistical range will be much shorter.

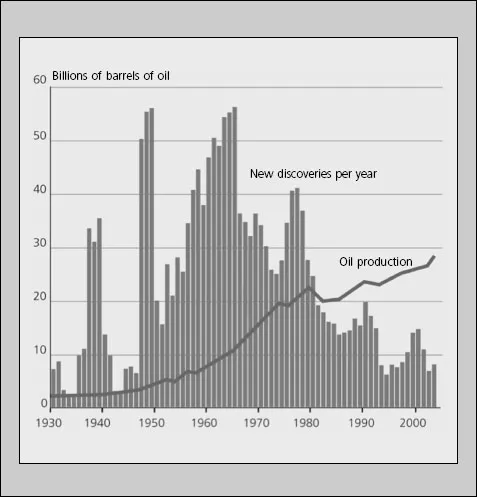

While new sources of oil were found regularly up to the beginning of the 1980s, no major discoveries were reported in the 1990s. Since then, far more oil has been consumed than discovered (see Figure 1.2).

Our current oil fields cannot be drained at any rate we wish. Once an oil field has been tapped, it quickly reaches a point where production cannot be increased. Once it has been half emptied, one speaks of a ‘depletion midpoint’. After that, it is practically impossible to speed up production. And because most current oil fields have already reached that midpoint, the production capacity of all oil fields in the world will begin to fall sooner or later – even though the range may statistically hold out for a few more decades. A number of oil-producing countries – such as the US, Mexico, Norway,

Egypt, Venezuela, Oman and the UK – have already passed their production peak, and others are soon to follow. A number of experts are therefore talking about peak oil production for the world – called ‘peak oil’ – which some say may have already been reached or may happen soon.3 When production is likely to decrease as demand increases, prices can be expected to skyrocket, as indeed they did before the recent economic crisis.

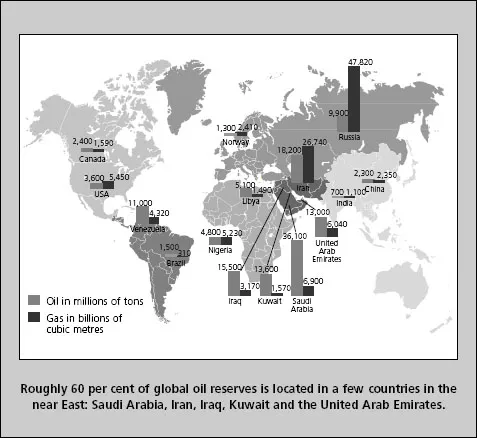

One more crucial factor has to be kept in mind: the remaining oil reserves are largely found in a small number of countries. In 2005, OPEC members had three quarters of all proven reserves. Indeed, five countries of the volatile region of the Persian Gulf – Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Iran – alone make up 60 per cent of global oil reserves.4 Instability therefore not only results from the absolute scarcity of oil reserves, but also from unequal distribution.

An energy policy based on renewables and energy efficiency will therefore not only protect the climate, but also make us less dependent on fossil energy, thereby reducing the potential for armed conflict over scarce reserves and resources.

Figure 1.2 Oil reserves: The gap between new discoveries and production widens

Source: BP, IEA, Aspo, taken from SZ Wissen 1/2005

1.3 Addiction to energy imports

Though Germany is sometimes touted as a global leader in renewables, the country imported 59 per cent of its primary energy consumption as oil or gas in 2005. And even when it comes to nuclear energy (12.5 per cent of primary energy consumption) and hard coal (12.9 per cent), Germany is hardly independent; 100 per cent of its nuclear fuel rods are imported, and more than 50 per cent of the coal burned in Germany comes from abroad.

The situation overall in the European Union (EU) is hardly better. The 25 member states currently import around half of their energy. If consumption and domestic production were to continue in line with the current trend, the share of imports would soon exceed two thirds. Domestic production continues to drop within Europe, but energy consumption is increasing considerably. As a result, the share of domestic energy will continue to drop if energy policy fails to change these trends.

Rising prices on the global crude oil market woke up energy politicians both in Germany and the EU a few years ago. In the autumn of 2005, oil prices began to skyrocket, reaching prices that surprised many; a barrel of crude oil (159 litres) was being sold for more than US$70. But even that price would double before the economic crisis suddenly brought prices back down. The effects of this price hike made themselves felt in consumer prices. While a family that consumes 3000 litres of heating oil a year only had to pay around €1000 in Germany in 2003, that figure had doubled by 2005/2006 and would double again by 2008.

Oil and gas imports to Germany rose to €66 billion in 2005, a 27 per cent increase over the previous year.5

Dependence upon energy imports not only means a heavy outflow of capital, but also narrows political leeway6 and, as we have seen over the past few years, increases the likelihood of armed combat over scarce resources.

Sustainable energy policy based on energy efficiency and renewables therefore strengthens local markets by redirecting capital that would have left the area to pay for energy imports into domestic energy sources. But such a policy also helps keep the peace by making battles for scarce resources unnecessary to begin with.

Figure 1.3 Global oil and gas reserves (2005) are restricted to a few regions

Source: BP Statistical Review 2006

1.4 Nuclear energy is not an alternative

A number of issues pertaining to nuclear energy have yet to be resolved and may be irresolvable:7

• The danger of a reactor meltdown like the one in Chernobyl (1986) remains, as events in July 2006 at Sweden's Forsmark nuclear plant revealed.8

• There is still no final repository for highly radioactive waste.

• The ‘peaceful’ use of nuclear energy cannot be completely separated from military applications.

• There is no perfect way to protect nuclear plants from terrorist attacks.

Germany, therefore, recently resolved to phase out its nuclear plants.9 In 2005, the Obrigheim plant was the first to be decommissioned. Since then, nuclear plant operators have been attempting to overturn the agreement they themselves signed in order to have longer commissions for their nuclear plants. They have discovered a new argument: climate protection. They claim that nuclear power would have to be replaced by coal plants and gas turbines, wh...