- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Landscapes of the Mind: The Music of John McCabe

About this book

Liverpool-born composer and pianist, John McCabe, established himself as one of Britain's most recorded contemporary composers as well as a celebrated performer and recording artist. This book covers every aspect of his compositions and will help guide both general and specialist listeners and performers through the so-called landscapes of the mind that his music evokes. The title was suggested by McCabe himself and his composing and performing life took him on journeys all over the world through a variety of landscapes, many of which are to be found in essence in his music. The detailed discography will help readers to find recordings of many of the works described in the series of articles written by a collection of experienced critics, performers, broadcasters and reviewers, and the copious illustrations and full pages of musical score provide a variety of insights into McCabe's life and work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The early years

John McCabe, c.1967.

Born in 1902, Frank McCabe, John McCabe’s father, was a physicist working for a large telephone communication company, ATM (later ATE). In his early years he was part of the pioneering group with Marconi, as evidenced by a photograph in John’s possession of Frank among a group of colleagues on Hampstead Heath near London in the late 1920s, celebrating the reception of transatlantic communication with a picnic. Tall, with brushed-back dark hair from a high forehead, in the style of the day, Frank was of the type who easily blended with a crowd, both in looks and dress. He was highly self-contained with a dry sense of humour, and appears (despite experiments in pottery and wood-carving in later life) to have been a stereotypical scientist with little interest in the arts or music. But his own early family life had been far from straightforward.

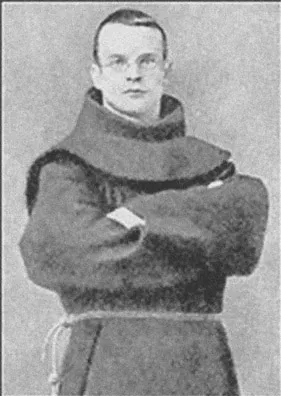

Joseph McCabe, John’s grandfather.

Joseph McCabe, Frank’s father and thus John’s grandfather, was of Irish/English stock and made a strong contrast with his son. Born the son of a Lancashire mill-worker in 1867, as a young man Joseph had taken his vows as a Christian monk at an Irish Roman Catholic monastery in Killarney in 1885, having entered an English seminary at the age of sixteen. As Father Anthony, over the next twelve years Joseph had risen through the monastic ranks, soon returning to England to continue his studies and then lecturing in a Catholic college in Forest Gate, Upton, West London. From 1893 to 1894 he studied philosophy and oriental languages at the University of Louvain in Belgium, returning to Forest Gate to his old post as lecturer. Appointed Principal of a Catholic college in Buckinghamshire in 1895, on Ash Wednesday 1896 he walked out, left the church, and from that point dedicated his life to secularism and rationalism as a lecturer, journalist and author. He settled in the north-west London area of Golders Green, married Beatrice Lee (1881–1960) in 1900 and became a sought-after lecturer, writing and successfully publishing many books on such diverse subjects as astronomy, popular science, history and anti-religion polemics until his death in 1955, only three years before his grandson entered university. Beatrice and Joseph raised a family of four – Frank, Athene, Dorothy and Ernest – but the marriage was unstable and eventually broke up by mutual consent in 1925. John McCabe’s only direct knowledge of his paternal grandmother, Beatrice (originally a hosiery worker’s daughter from Leicester), is that she ended up living in self-imposed rural poverty on the South Downs, in a house surrounded by animals; he believes that she was an early and outspoken feminist. Given such an insight into his turbulent family life, Frank’s self-possession and pursuit of scientific order perhaps comes as no surprise.

John McCabe expresses his relationship with his father as one of great respect, a phrase that also tells something of a distance between them. Frank hardly ever attended any of his son’s performances, even those at school. However, he shared his own interests, fishing being one, with his son as well as he could. John has strong memories of a later fishing trip in a Lakeland stream with his father, when he had been given a fresh fish-head as bait and, much to his delight, had caught an eel. This created a memorable scene with his father and mother struggling to secure and dispatch the eel, finally cooking it and serving it for supper.

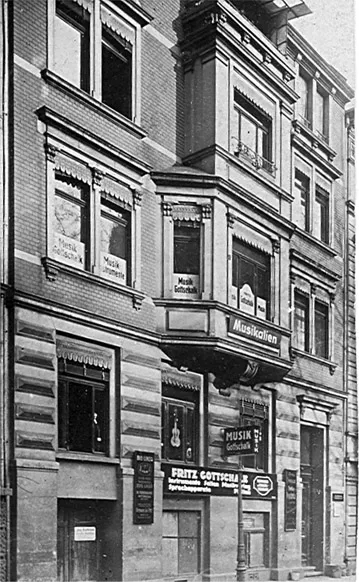

In complete contrast, John’s mother, Elisabeth McCabe, was extrovert, energetic and artistic. A fine-looking and attractive woman, Elisabeth Herlitzius was born in Mülheim in the West German industrial region of the Ruhr in 1913 as a member of a large family. The Herlitzius family roots could be traced back to Sweden, Finland and even Spain, and Elisabeth was a talented amateur violinist who, throughout her days, bubbled with energy and interest in the world of the arts and life in general. Her uncle Franz Gottschalk, a zither player, had emigrated to the USA and eventually became a well-known orchestral conductor. Another Uncle Fritz Gottschalk owned a large music shop in Cologne, selling sheet music and instruments and specialising in violins. A photograph of this extensive emporium is in Elisabeth’s photograph album, still in John’s possession.

Notes on the back of this photograph in her handwriting tell the stark tale of the closure of the shop by the Nazis during the Third Reich, and the deportation of the family to what is described as a ‘detention’ camp. All this might suggest a Jewish family background, as does the family surname, but this has never been investigated. Photographs of Elisabeth’s father and mother show a solidly middle-class couple. As far as is known, her father, Paul Herlitzius, had emigrated to Liverpool before the First World War, was interned during the war and continued to work there afterwards, to be joined by his wife and daughter in the early 1920s. Elisabeth could remember moving back and forth between Liverpool and Mülheim as a child and remembered the sadness of regular separation from her parents, which affected her insecurities in later life. She could remember the French occupation of the Ruhr and also the brief Communist government in the years leading to 1923.

It is certain that Elisabeth had many of the attributes of the stereotypical Jewish mother, and dedicated much of her life to her only child, becoming, in John’s own words, a huge influence on him. Exactly when her family finally settled in Liverpool is not yet known, nor how and when she met Frank except that he attended German-language evening classes at ATM given by Elisabeth. An early album snap taken by Frank shows a winsome Elisabeth, a daisy tucked behind one ear, gazing alluringly into the camera. Elisabeth exuded charm and always was able to use her eyes to her advantage, never shrinking from engaging anyone that interested her in conversation. Whether her lisp was acquired or natural, it added to her strong personality and charisma, and it is perhaps not surprising that the more saturnine Frank fell for her.

Uncle Fritz’s music shop, Cologne.

Being married to a German wife was not the most comfortable of situations in England in the years immediately before the Second World War, and John’s birth – in the then prosperous suburb of Huyton, Liverpool on 21 April – took place a short time before the declaration of war with Germany in 1939. John’s first six years were lived under the periodic barrage of the blitz and the general privations of wartime life with food rationing and restricted travel. Frank continued his work in the important and nationally vital and secret area of the telecommunications industry, also acting as an air-raid warden within the community. For information and relaxation, the family would listen to the BBC Radio Home Service, with regular news, talks, comedy and feature programmes and often to the Third Programme, where the Reithian principles of culture for the masses encouraged the broadcast performances of new music as well as the established classics. As further family entertainment in the evenings, very likely at Elisabeth’s instigation, they were able to enjoy listening to their extensive collection of shellac gramophone records, played, through Frank’s professional interest and connections, on the latest technological equipment. One of John’s earliest memories is of climbing out of bed late in the evening, and sitting half-way down the staircase to listen to the enthralling orchestral sounds of Brahms’ Variations on the Saint Anthony Chorale coming from behind the living room door.

John McCabe aged 2; with his mother, Elisabeth; with his father, Frank.

Towards the end of his second year, in the early spring of 1942, a chance accident in the home was to prove a profound experience, changing the direction of his life. An inquisitive child, John had assembled some favou-rite but somewhat inappropriate materials as the focus of his play on the hearth-rug by the welcome warmth of the living-room fire. Houses in those days had no central heating and often the fire burnt in the hearth all day, especially when it also heated the water. Elisabeth found her two-year-old son happily engaged in mixing ink with marmalade on the hearthrug, and, unsurprisingly, somewhat dismayed, she quickly removed the ink-bottle from his grasp, placed it on the nearby mantelshelf above the fire, then grasped the marmalade jar and returned it to the nearby kitchen cupboard.

Open fires were always protected by strong wire-mesh fireguards, and the safety-conscious McCabes had invested in a large one, bigger than those owned by other similar families. The young John obviously saw the wiremesh wall as a challenge and proceeded to climb the fireguard in search of the confiscated ink-bottle. Toppling over the fireguard, he fell directly on to the blazing coal fire, landing on his right torso and arm and setting light to his clothes. Elisabeth remembered returning to the room, minutes later, not summoned by cries of alarm, but startled by the reflection of flames on the opposite wall and the whimpering of her shocked and wounded child. Severely burned, John was kept sedated for a week to assuage the pain. In those years of austerity, the most effective anaesthetic available was cider, regularly administered in order to keep the dangerously ill child in a state of relaxation. John states that he owes his life to Dr Charles Garson, a doctor who had qualified in India and who practised in Liverpool at that time. Garson was a string player and took a great interest in his young musical patient, performing conjuring tricks to amuse him, and later John was to be presented with several of the same Doctor’s miniature scores, which he still owns.

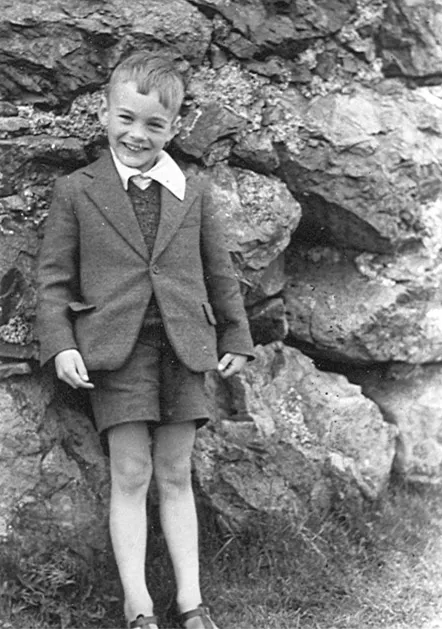

John McCabe in c.1945.

Over the subsequent weeks, months and years, John, whose immune system had been assaulted by the accident, fell victim to many illnesses including pneumonia, meningitis and mastoiditis, which affected his hearing and, at one point, left him deaf for a time. His formative years were therefore circumscribed by illness and spent mostly in the confines of the Huyton 1920s detached house and its garden, supervised by his mother. Attempts to integrate him into school were foiled by exhaustion and subsequent illness, and a three-week stretch was the longest he ever achieved during the primary years school phase, which in England was from five until eleven years. But although this only child, alone for most of the time with his mother in the home, had to make his own entertainment and construct his own education with his mother’s help, John remembers the time as a happy one, in a house often full of children. Interestingly, as he later pointed out, the family snapshots show John always in the company of girls and women. He also felt that this period of constant battle with illness made him resilient and, in his words, tough but not an isolate, and he enjoyed the company of other children.

Two years or so after the traumatic accident, John was already reading, writing and drawing with enthusiasm. He was a voracious reader who, not unlike many other children in those days, did not need to learn to read at school because he had already acquired the skill at his parents’ knees. Not surprisingly, books were a significant part of the family possessions, and the habit of reading, with the entrance into the world of knowledge and the imagination this afforded him, was to prove the foundation for a lifetime’s practice. An artistic mother naturally provided her son with writing and drawing materials, although, interestingly, Elisabeth never in John’s memory played her violin to him, despite her membership of an amateur string quartet. However, sheet music somehow came his way, and at five years old he became intrigued, as do many children of this age, by the shapes of western music notation. To a five-year-old, already accustomed to listening to full-length classical works, these musical symbols were just as interesting as the shapes of letters and words, and he naturally wanted to make up his own. With the attention of his mother never far away, these drawings were praised and encouraged and soon a music manuscript book with staves on each page was provided for him to experiment further. Not surprisingly, encouraged by his mother, the child followed this interest and was soon filling up sheets of manuscript paper with musical notation which were grandly named ‘symphony’ and given a key, like the examples he was used to hearing at home. Although most of these childish exercises were copies of music notation found around the house (for example, a sixbar précis of the melody from Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto) John claims that he had a strong inner aural awareness of what he was writing, although he had no access to any musical instrument on which to experiment.

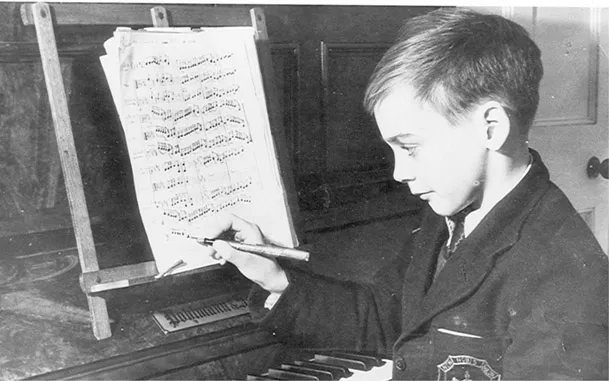

The early composer.

The McCabe house in Rupert Road, Huyton, c.1945.

In post-war British society a child composer was seen as being remarkable and noteworthy enough to feature in the local paper, and a press photograph taken at about the age of six shows a diminutive McCabe seated at an upright piano with sheets of childish music manuscript on the music stand beside him. This piano was purchased by his parents and installed in the home in his sixth year, and he was immediately placed with a local piano teacher, Marjorie Madge, who was happy to take him on, since a pupil who had never touched a keyboard but who both read and wrote music as a hobby, and had an extensive and detailed knowledge of the classical repertoire, must have been an unusual and interesting challenge. It was only at this time that he began to write pieces of music with any real understanding. By the age of eight he was playing fluently and continued to write increasingly complex pieces. His piano teacher encouraged him to explore music on his own, not insisting on a preordained and orderly sequence of pieces, and John sees this as one of the greatest gifts that she gave to him. Throughout his childhood, McCabe remembers that he only spent his pocket money on records and music scores. At the age of eight he had bought the set of records of Alan Rawsthorne’s Symphonic Studies (recorded in 1946) and he was to meet the composer the following year at the house of his next piano teacher, Gordon Green.

The young John McCabe with his cat, Clifford.

In late 1947 Elisabeth decided to seek professional advice on how best to continue her son’s musical education and wrote a letter to Malcolm Sargent, then a nationally acclaimed conductor, and to John Barbirolli, principal conductor at the Hallé Orchestra in nearby Manchester. Sargent did not reply, but Barbirolli took the trouble to do so, advising that she should seek advice from Robert Forbes, Principal of the Royal Manchester College of Music. At the age of eight, John was taken for an audition with Forbes in Manchester during which he was also seen by the keyboard professor, Gordon Green. Forbes was of the opinion that the young McCabe had no musical talent, but Green, fascinated by the many pages of compositions that were also presented as well as identifying latent talent in his playing, accepted John as a private pupil and placed him forthwith under one of his star pupils, Sheila Dixon, who lived in Liverpool and who became engaged to and eventually married Oliver Vella, a cellist in the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. One of the first compositions that John acknowledges as a significant piece is an Adagio for Cello and Piano, written with these people in mind, and performed by them as an encore at a local recital.

The age of nine appears to have been an important year in John’s development, and it was during the summer of 1949 that Elisabeth and Frank, following medical advice, decided to take their son for the summer months to the countryside, for fresh air and exercise. They were able to rent Godrill Cottage in Patterdale in what is now the county of Cumbria, at the heart of one of north-western England’s most beautiful natural areas known generally as The Lake District and situated some one hundred miles or so north of Liverpool. The isolated cottage stood by a fast-flowing mountain stream and its bridge, in a valley surrounded by mountainous hills known as Fells. The area is infamous for wet weather, but John remembers this summer as a golden time with only three days’ rain in three months. Frank joined them at weekends and when he could find the time; this is when the fishing trip, mentioned before, took place. Frank also took his son walking on the Fells where they climbed up to Angle Tarn, a small lake up in the folds of the hills above Pat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- List of contributors

- 1 The early years

- 2 The professional years

- 3 Symphonic and concertante works

- 4 The wind chamber music

- 5 Chamber music for strings

- 6 Composing processes: An interview with John McCabe

- 7 The music for brass and wind

- 8 The piano music

- 9 The vocal music

- 10 Music for theatre, film and television

- Discography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Landscapes of the Mind: The Music of John McCabe by George Odam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.