![]()

Section 1

Rethinking the Relationship between Education and Development

![]()

2

Human Capital and Development

Milan Thomas with Nicholas Burnett

Introduction

This chapter reviews theory and evidence on the economics of human capital, with an emphasis on the education aspect of human capital and its impact on economic growth in developing countries. We focus our discussion on development as measured by economic growth (i.e., change in gross domestic product) while recognising that there is a range of other dimensions that human capital accumulation influences, such as social development and health.

Tracking the evolution of economic thought on this topic from its origins to its inclusion in macroeconomic growth models, we first review the concept of human capital and then labour market research on its relationship with individual earnings before turning to its impact on aggregate income. We review evidence primarily from human capital’s inclusion in neoclassical growth models rather than endogenous growth models because the former is relatively strong at explaining cross-country differences in national income while the latter is more pertinent to advanced economies in the global technological frontier (Barro and Lee 2013). We also consider how the estimation of education’s impact on development has changed due to recent advances in the measurement of human capital.

Understanding the nuances of human capital’s role in development is not an academic exercise. Evidence on it can guide public policy and encourage it so that scarce resources are channelled to impactful investments in human productive capacity that will accelerate economic growth and poverty reduction. In addition to reviewing research on human capital’s impact on growth through labour force productivity, we highlight emerging evidence on the importance of human capital investment for promoting equity and environmental sustainability – both of which will be critical for sustaining economic growth through the 21st century.

Economics and human capital

Sparked by the Industrial Revolution in Britain, the last two hundred years have been an era of unprecedented global economic development. After millennia of global economic stagnation (Clark 2007), gross domestic product (GDP) in today’s advanced economies grew from $1,000 per capita in 1820 to $21,000 in 2000 (Maddison 2001). Meanwhile, GDP per capita in today’s developing countries grew only fivefold over that period. Thus, while average standards of living measured by income, life expectancy and other development indicators show unambiguous improvement in the global average standard of living, the benefits of growth have been unevenly distributed within and among nations (Ostry, Berg and Tsangarides 2014).

Although the income gap between early industrialisers and today’s developing economies remains large, over the past fifty years developing countries have exhibited growth rates far exceeding the average growth of Western Europe since industrialisation (1.7% per year, Maddison 2001). Between 1980 and 2012, average annual GDP per capita growth was 2.8% in low- and middle-income countries, compared to 1.8% in high-income countries (World Bank database). However, there has been wide divergence in rates of development since 1960, when per capita income in some East Asian economies (Taiwan, South Korea) was comparable to that of poor African countries like Ghana, Senegal and Mozambique (Rodrik 1995). In the following decades, some East Asian incomes have grown rapidly to reach the level of leading Western economies, while GDP per capita in sub-Saharan Africa is less than 5% of the average income in high-income countries (US$37,000).

In response to these global disparities, growth accounting has emerged as a major branch of modern macroeconomics. This subfield analyses the drivers and mechanisms behind economic growth to understand why average national or subnational incomes diverge over time. Similarly at the microeconomic level, labour economics focuses on understanding variation in earnings of individual economic agents.

Central to both of these subfields of economics is the concept of human capital. Capital refers to factors of production that generate goods or services in an economy – the various inputs that produce economic output. For decades, mainstream economic theory had emphasised physical, tangible capital (machinery, natural resources, factories, equipment, etc.) as the strongest source of short-run economic growth, with exogenous and inexplicable technological change serving as the catalyst for long-term growth.

However, intangible capital also has a role in the history of economic thought. As far back as 1776, Adam Smith formally recognised the productive capabilities of the populace as part of a nation’s capital stock in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Nelson and Phelps (1966) emphasised the role of human capital in enabling economies to adopt technologies and new ideas discovered elsewhere, while Romer (1989) identified the causal role of human capital as the generation of ideas and development of new products. Mankiw (1995) defines ‘knowledge’ as the sum total of technological and scientific discoveries (written in textbooks, scholarly journals, websites, etc.), and defines ‘human capital’ as the stock of knowledge that has been transmitted from those sources into human brains through learning. More recently, Frank and Bernanke (2007: 355) define human capital as “an amalgam of factors such as education, experience, training, intelligence, energy, work habits, trustworthiness, and initiative that affect the value of a worker’s marginal product.” In short, human capital includes anything that contributes to the productive capacity of the workforce.

Still, from its foundations in the early modern work of Ricardo, Mills and Malthus until the 1960s, economic thought on the wealth of nations has been dominated by the study of tangible capital accumulation, and the human element of economic growth was largely neglected. Led by Schultz (1961), Denison (1962), Becker (1964) and others, there was a renaissance for human capital in economics in the 1960s, from which emerged a debate on the role of education in development. There is a broad distinction between theories by which observable measures of human capital like schooling are directly useful to economic productivity (Becker 1964; Nelson and Phelps 1966) and those in which they are not. According to Marxian critiques, the positive relationship between education and earnings reflects schooling’s role in building workers’ capacity to obey orders and adapt in capitalist societies (Bowles and Gintis 1975).

At the other extreme of the productive human capital theory of education is the signalling theory, in which education serves as a signal of inherent ability and is not independently useful in production processes (Spence 1973). By this set of theories, education does not increase the productive capacity of an economy but instead overcomes labour market information imperfections. Individuals with high levels of innate ability elect to invest in education to signal to employers that they are of high skill and deserving of higher wages. The disutility of education is prohibitive for low-ability workers, so they do not invest in education and earn lower wages. Although the bulk of empirical studies support education as a productivity-enhancing investment (as we discuss below), evidence does not unambiguously support human capital theory over signalling theory nor are the theories necessarily mutually exclusive.

Human capital and the labour market

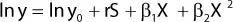

While the central economic role of education had been posited centuries before, human capital did not take off in economic modelling until the 1960s, in part because of difficulties with measurement. Among the earliest applications of human capital in economics was explaining differences in wages in developed economies. Mincer (1974) proposed that years of schooling could be used as a measure of human capital, claiming that the primary reason that children attend school is for labour market preparedness. Based on that idea, he formulated the human capital earnings function below:

where ln is the natural log operator, y is an individual’s labour market earnings, s is the individual’s years of schooling, X is years of labour market experience and y0 is the expected base wage of a person with no experience and no education. The variables r and B1 are the average returns to education and work experience respectively, which the earnings function is designed to estimate.

This type of equation has been specified in a number of ways, including different characteristics such as ethnicity and sex, and is the basis for a vast literature testing the relationship between education and earnings. For decades to follow, empirical analysis of human capital would be largely based on education attainment as measured by years of schooling (for micro studies) and average years of schooling (for macro studies).

Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2004) analyse the wealth of evidence that emerged from applying the Mincerian approach to a variety of labour markets. Their review finds a 10% increase in earnings for an extra year of education at the mean of the distribution (i.e., r = 0.1). A survey by Card (1999) similarly finds a 6–10% return to an additional year of education. However, the marginal return to a year of schooling varies substantially by geography, by level of education, by demographic group and over time. Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2004) find a premium to female education (9.8% return to a year of female education versus 8.7% for male education). Psacharopoulos and Patrinos (2008) show that returns to education are higher in low-income areas; labour market evidence for working males from the 1960s to the 1990s suggested that in developing countries, primary education provided the highest returns, with the marginal benefit from education diminishing in years of schooling.

However, more recent evidence from the 1990s and 2000s (summarised by Colclough, Kingdon and Patrinos 2009) suggests that there has been a shift in the relative returns of different education levels, with postprimary returns rising above primary school returns in developing countries. For example, Behrman, Birdsall and Szekely (2003) find that for a sample of 18 Latin American countries, returns to tertiary education increased greatly throughout the 1990s while returns to primary and secondary education fell. This could be interpreted as evidence that skill-biased technological change has increased demand for workers with higher education (lowering the relative wages of low-skilled workers), that expansion of primary education has saturated labour markets with workers with basic education (increasing the premium for workers with postprimary education), that the quality of primary education has declined (reducing the productivity gains associated with primary school completion) or some combination of these explanations.

There is also growing evidence that early childhood education yields high economic returns (Heckman 2011). Based on longitudinal data from the High/Scope Perry randomised controlled experiment, Schweinhart et al. (2005) find that American children raised in poverty that completed a high-quality preschool program had significantly higher rates of employment in adulthood than individuals in the control group. Median annual income for the preschooled group was also 36% higher at age 40. Furthermore, comparison of the two groups’ propensity for crime and health suggests large public externalities of early childhood education. Similar evidence for developing countries is scarce.

While Mincer-type studies provide empirical evidence that education accounts for much of the variation in individual earnings in developing countries, they face several limitations. The approach only allows the study of formal employment with wage data (often for males) and thus does not capture the returns to education within the informal economy. However, there is emerging evidence that education increases informal sector productivity (e.g., De Brauw and Rozelle 2006 for rural China; Nguetse Tegoum 2009 for Cameroon; Arbex et al. 2010 for Brazil; and Yamasaki 2012 for South Africa), as well as ability to secure employment in the growing digital economy (Results for Development Institute 2013).There is also an established literature (reviewed in Huffman 2001) showing that schooling improves farm yields, particularly in settings where farmers are able to benefit from their education by accessing affordable agricultural technologies.

Furthermore, the Mincerian approach was critiqued by Heckman, Lochner and Todd (2003) for not being able to capture the complexity of modern labour markets. Mincerian returns do not capture the value of education in increasing a worker’s employment stability (discussed for the US case in Cairo and Cajner 2014), which is particularly relevant in postrecession economies with high unemployment rates. In addition, it is unclear that years of schooling (which do not account for quality of education) are the optimal measure of an individual’s human capital. There is growing focus on microeconomic data that captures skill levels acquired through education (an output of education) rather than years spent in school (an input into education). This measurement issue with respect to human capital is discussed further later in this chapter.

Human capital and economic growth

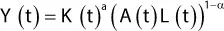

In the 1950s, Solow (1956) and Swan (1956) investigated the divergence in economic production of nations using exogenous growth models, which specify per capita income as a function of physical capital, size of the labour force, assumed (exogenous) rates of technological progress, saving, population growth and residual total factor productivity (which augments the productivity of capital and labour). All inputs into economic production are thus tangible (physical capital and labour). The basic exogenous growth model is applied to data by regressing log per capita income on log savings rate and log of the sum of the depreciation rate, technological growth rate and population growth rate.

As discussed in Mankiw, Romer and Weil (1992), empirical testing shows that the basic exogenous growth model has promising features but is ultimately inconsistent with reality. A typical Solow-Swan regression explains half of the variation in per capita income, with the remaining half attributed to the residual (total factor productivity). However, the estimated magnitudes of the effects of saving and labour force growth are too great. The difference in income between India and the USA, for example, could only be explained by implausibly huge differences in physical capital stock. By the basic specification, the implied value of capital’s share of income is 0.6, but globally the true value of capital’s share of income is about 0.3.

where Y(t) is output for time period t, K(t) is the physical capital stock at time t, L(t) is the size of the labour force at time t, A(t) is a residual, catchall variable, and α is the elasticity (responsiveness) of output with respect to physical capital. A and L grow over time at exogenous rates g and n, respectively, while a constant fraction of output s is saved in each period and invested in physical capital.

These weaknesses suggest that the basic Solow-Swan model omits key variables that account for economic growth. Given the strong evidence that education is a central determinant of earnings at the individual level, it should follow that human capital is a determinant of income and growth of nations and thus should be included in Solow-Swan-type growth accounting exercises. This idea was tested empirically by Mankiw, Romer and Weil (1992), who augmented the Solow-Swan exogenous growth model w...