![]()

Part One

Transformation of Food Systems

and the Small Farmer:

Key Concepts

![]()

Chapter 1

Small Farms and the Transformation of

Food Systems: An Overview

Ellen B. McCullough, Prabhu L. Pingali and Kostas G. Stamoulis

Introduction

By making a strong case for the importance of agriculture in poverty reduction, even in developing countries with largely urbanized populations, the 2008 World Development Report has continued the renewed interest in agriculture as a force for poverty reduction (World Bank, 2008). Research has shown that rural poverty reduction, resulting from better conditions in rural areas and not from the movement of rural poor into urban areas, has been the engine of overall poverty reduction (Ravallion et al, 2007). Organizational changes that are currently underway in developing-country food systems necessitate a new look at agriculture’s role in poverty reduction with an eye on the changing rural economy. The reorganization of supply chains, from farm to plate, is fuelling the transformation of entire food systems in developing countries. With the changing rural context in mind, we revisit prospects for poverty reduction in rural areas, particularly in the small farm sector. The transformation of food systems threatens business as usual but offers new opportunities for smallholder farmers and the rural poor.

The purpose of this volume is to take stock of important trends in the organization of food systems and to assess, with concrete examples and case studies, their impacts on smallholder producers in a wide range of contexts. This volume brings together relevant literature in a consistent manner and examines more holistically the issue of changing food systems, moving beyond the focus of supermarkets, which has been a dominant concern in recent literature. We focus on domestic markets as well as exports, and on a wide range of sub-sectors, not just fresh fruits and vegetables and dairy. This chapter begins with a description of changing consumption patterns in developing countries. Then we highlight organizational changes that have taken place along the food chain, recognizing important differences between countries, and exploring interactions between traditional and modern chains in countries where food systems are transforming. We present a framework for evaluating impacts at the household level, pulling together empirical evidence in support of the framework. We close with a policy discussion on managing the transition for smallholder households, which focuses on linking smallholders into modern food chains, upgrading traditional markets and providing exit strategies for those who are marginalized by the transformation process.

The transformation: An overview

In this chapter, we lay out three different typologies for food systems that correspond roughly with the development process. The first is a traditional food system, characterized by a dominance of traditional, unorganized supply chains and limited market infrastructure. The second is a structured food system, still characterized by traditional actors but with more rules and regulations applied to marketplaces and more market infrastructure. In structured food systems, organized chains begin to capture a growing share of the market, but traditional chains are still common. The third type is an industrialized food system, as observed throughout the developed world, with strong perceptions of safety, a high degree of coordination, a large and consolidated processing sector and organized retailers.

Major global shifts in consumption, marketing, production and trade are brought about, above all, by four important driving forces associated with economic development: rising incomes, demographic shifts, technology for managing food chains and globalization. As these changes are played out, modern chains capture a growing share of the market, and food systems transform. The variable that differs most strikingly between food system typologies is the share of the food market that passes through organized value chains. We identify economic factors that explain how modern chains capture a growing share of food retail over time, and we explore specific differences between organized and traditional chains. Then we examine the implication of the spread of modern chains from the perspective of chain participants and with respect to the entire food system. In practice, the boundaries between these food system typologies are not easily discernible. Nor is the path from traditional to structured to modern a linear one. A mix of different types of chains can be found within one country depending on the commodity involved, the size of urban centres and linkages with international markets (Chen and Stamoulis, this volume).

Understanding how different types of chains relate to each other is important for predicting future opportunities for smallholder farmers as food systems reorganize. In developing countries, the food system is typically composed of domestic traditional chains, domestic modern chains and export chains, which are usually exclusively modern. When traditional marketing systems fail to meet the needs of domestic consumers and processors, modern retailers develop mechanisms for bypassing the traditional market altogether. Modern food chains in developing countries advance rapidly due to global exposure, competition and investment, while traditional chains risk stagnation due to underinvestment. As the gap between traditional and modern food chains grows ever wider, the challenge of upgrading traditional chains becomes more pronounced. The entire food system’s transition from traditional to structured is hindered as resources and attention are diverted from upgrading traditional markets in favour of bypassing them.

Assessing the full implications of changes for rural communities and, in particular, smallholder agriculture, requires an analysis of how risks and rewards are distributed both in traditional food systems and modern ones. As production and marketing change, there are obvious implications for smallholder farmers via changes in production costs, output prices and marketing costs. But changes in processing, transport, input distribution and food retail also impact rural households via household incomes (e.g. labour markets, small enterprises) and expenditures (e.g. food prices).

From farm to plate, one overarching trend is the rising need for coordination in modern food systems relative to traditional ones, and the transaction costs that are introduced as a result. Coordination helps to ensure that information about a product’s provenance travels downstream with the product. It also helps to ensure that information about consumer demand and stock shortages/surpluses is transferred upstream more efficiently to producers (King and Phumpiu, 1996). Improving coordination along the supply chain reduces many costs but introduces new ones (Pingali et al, 2007). We explore and evaluate different strategies for coordination later in the chapter.

Towards dietary diversification

Brought about by rising incomes, demographic shifts and globalization, dietary change is sweeping the developing world. Consumers are shifting to more diverse diets that are higher in fresh produce and animal products and contain more processed foods. Shifts in food consumption parallel income growth, above all, which is associated with higher value food items displacing staples (Bennett’s Law). The effect of per capita income growth on food consumption is most profound for poorer consumers who spend a large portion of their budget on food items (Engel’s Law). A sustained decline in real food prices over the last 40 years has reinforced the effect of rising incomes on diet diversification.

Per capita incomes have risen substantially in many parts of the developing world over the past few decades. In developing countries, per capita income growth averaged around 1 per cent per year in the 1980s and 1990s but jumped to 3.7 per cent between 2001 and 2005 (World Bank, 2006). Growth rates have been most impressive in east Asia and slightly less spectacular in south Asia. Declining growth rates have been reversed since the 1990s in Latin America and since 2000 in sub-Saharan Africa. Income growth has been accompanied by an increase in the number of middle class consumers in developing countries, particularly in Asia and Latin America, whose consumption patterns have diversified (Beng-Huat, 2000; Solamino, 2006).

Beyond income growth, dietary diversification is also fuelled by urbanization and its associated characteristics, rising female employment and increased exposure to different types of foods. Globally, urban dwellers outnumbered rural populations during 2007 (Population Division of UN, 2006). Feeding cities is now a major challenge facing food systems.

Female employment has at least kept pace with population growth in developing countries since 1980 (World Bank, 2006). Female employment rates have risen substantially in Latin America, east Asia, and the Middle East and north Africa since the 1980s.

Urban consumers typically have higher wage rates and are willing to pay for more convenience, which frees up time for income-earning activities or leisure. Therefore, they place a higher premium on processed and pre-prepared convenience foods than do rural consumers (Popkin, 1999; Regmi and Dyck, 2001). Rising female employment also contributes to this phenomenon (Kennedy and Reardon, 1994). Smaller families are typical of urban areas, so households can afford more convenience in terms of processed and prepared foods.

Globalization has led to increased exchanges of ideas and culture across boundaries through communication and travel, leading to a tightening of the global community which is reflected in dietary patterns, such as increased consumption of American style convenience foods. Urban consumers are exposed to more advertisements and are influenced by the wide variety of food choices available to them (Reardon et al, this volume).

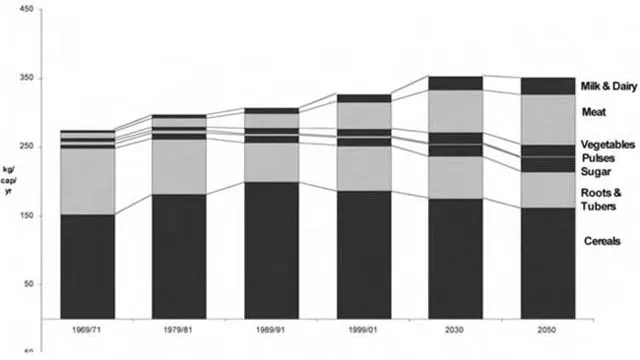

Dietary changes have played out differently in different regions and countries, depending on their per capita incomes, the degree of urbanization and cultural factors. The most striking feature of dietary change is the substitution of traditional staples for other staple grains (i.e. rice for wheat in east and southeast Asia) and for fruits and vegetables, meat and dairy, fats and oils (Pingali, 2007). Per capita meat consumption in developing countries tripled between 1970 and 2002, while milk consumption increased by 50 per cent (Steinfeld and Chilonda, 2006). Dietary changes are most striking in Asia, where diets are shifting away from rice and increasingly towards livestock products, fruits and vegetables, sugar and oils (Pingali, 2007). Diets in Latin America have not changed as drastically, although meat consumption has risen in recent years. In sub-Saharan Africa, perhaps the biggest change has been a rise in sugar consumption during the 1960s and 1970s (FAOSTAT, 2006). Cereals, roots and tubers still comprise the vast majority of sub-Saharan African diets, and this is expected to continue into the foreseeable future (FAO, 2006). Total food consumption in developing countries is projected to increase in coming decades, so dietary diversification does not necessarily imply that per capita consumption of any food products will decline in absolute terms (Figure 1.1). However, by 2030, absolute decreases are expected in per capita consumption of roots and tubers in sub-Saharan Africa and of cereals in east Asia (FAO, 2004). Since cereals are used as inputs in animal production, total cereal demand will not decrease due to indirect consumption.

Source: Data from FAO, 2006

Figure 1.1 Trends and projections for dietary diversification in east Asia

Trends in food systems organization

Consumption of higher value products is on the rise in developing countries, and supply chains are ready to meet these demands. But which chains will reach dynamic consumer segments in developing countries, and which farmers will supply these chains? From farms to retail, technology and ‘globalization’ are the most important drivers of reorganization of the chains linking producers and consumers. Innovations in information and communications technology have allowed supply chains to become more responsive to consumers, while innovations in processing and transport have made products more suitable for global distribution. Technological innovation in food supply chain management has arisen in response to volatility in consumer demand (Kumar, 2001). New communication tools, such as the Universal Product Code, which came on line in the 1970s, have improved the efficiency of coordination between actors along the supply chain to shorten response times to demand fluctuations (King and Venturini, 2005). Packaging innovations throughout the second half of the 20th century continued to extend food products’ shelf lives (Welch and Mitchell, 2000). Meanwhile, a downward trend in transportation costs and widespread availability of atmosphere-controlled storage infrastructure have made it cost-effective to transport products over longer distances. Crop varieties have been tailored specifically to chain characteristics, for example to meet processing standards or to extend shelf life. Conventional breeding and, more recently, biotechnology, have allowed these shifts.

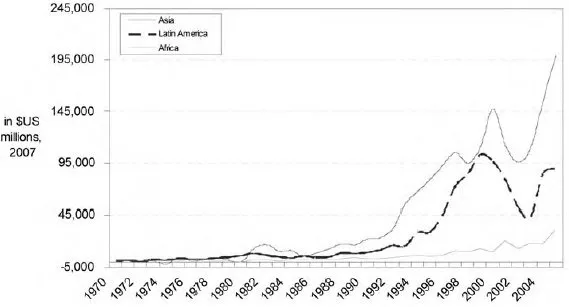

Source: Data from OECD, 2007

Figure 1.2 Annual FDI net inflows into developing countries by region from 1970

‘Globalization’ in retail and agribusiness is marked by liberalization of trade as well as of foreign direct investment (FDI). Trade has maintained a constant share in global food consumption but is shifting towards higher value products, such as processed goods, fresh produ...