![]()

PART 1

Education for sustainable development in higher education

![]()

1

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE

Re-purposing higher education and research

Yoko Mochizuki and Masaru Yarime

Introduction

Normative discussions surrounding the role of higher education in contributing to sustainable development abound, from the perspectives of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), Sustainability Education, or more specifically Higher Education for Sustainable Development (HESD). Despite familiar calls for interdisciplinarity and more research to advance higher education to facilitate a global transition to sustainability, however, such discussions rarely involve natural scientists, engineers or technologists striving to establish ‘Sustainability Science’ as an academic field and are often silent on crucial relations between ESD and Sustainability Science in the context of re-purposing higher education and research. This can be partly explained by different ‘epistemic communities’ formed by ESD experts on the one hand, and scientists who promote Sustainability Science on the other. This chapter discusses potential synergies between ESD and Sustainability Science by 1) contextualising them in global ‘policyscapes’ (Carney 2009), and 2) exploring how ESD and Sustainability Science can reinforce each other.

Literature investigating links between ecological science and environmental education has long pointed out the importance for knowledge producers and knowledge users to identify problems and develop solutions to them together (see, for example, Beal et al. 1986; Maarleveld and Dabgbégnon 1999). In recent years, literature on ‘social learning’ for natural resources management has inspired practitioners and scholars of ESD to highlight the importance of stakeholder communication and interaction in change-oriented learning processes (Lotz-Sisitka 2012). The added value of this chapter is not so much underscoring the importance of developing learning partnerships as drawing attention to the fact that calls for integration of knowledge are gaining prominence in an emerging policy common sense or global ‘policyscapes’. Whereas context embedded research and education, starting from real-life problems, are important aspects of Sustainability Science and ESD, the purpose of this chapter is not to show how they manifest themselves in different settings. Rather, this chapter intends to enhance HESD stakeholders’ understanding of global frameworks that would affect directly and indirectly the implementation of HESD on the ground in the coming decade. The chapter aims at enriching the field of HESD by identifying common challenges and opportunities faced by ESD and Sustainability Science in the international policy community’s ongoing efforts to set post-2015 education and development agendas as well as the scientific community’s efforts to set a new knowledge agenda.

ESD and sustainability science in global ‘policyscapes’

In 1999, UNESCO and the International Council for Science (ICSU) organised the World Conference on Science in Budapest and declared the importance of ‘science in society, and science for society’. The concept of ‘Sustainability Science’ was originally introduced at the World Congress ‘Challenges of a Changing Earth 2001’ in Amsterdam organised by the ICSU and other international organisations. Although the linkages between ESD and Sustainability Science have been recognised since the beginning of the United Nations (UN) Decade of ESD (DESD 2005–2014) by ESD researchers as well as advocates of Sustainability Science in Japan, where the government has supported these two initiatives through various funding schemes, it was not until recently that UNESCO explicitly came to endorse the idea of Sustainability Science.

In 2011, the Japanese National Commission for UNESCO submitted to the UNESCO Secretariat a proposal to request that UNESCO introduce the concept of ‘Sustainability Science’ in formulating its programmes (MEXT 2011). Consequently, ‘Sustainability Science’ came to be recognised in UNESCO’s medium-term strategy covering the period between 2014 and 2021 as ‘integrated, “problem-solving” approaches’ to science and engineering for sustainable development which ‘draw on the full range of scientific, traditional and indigenous knowledge in a trans-disciplinary way to identify, understand and address economic, environmental, ethical and societal challenges’ (UNESCO 2014a: 22, paragraph 52). This section contextualises ESD and Sustainability Science in relation to the ‘real world’ of global politics, international organisations, and international agenda setting – in other words, in global ‘policyscapes’ (Carney 2009), created around notions of sustainable development and composed of a particular constellation of visions, values, policies and practices. It pays special attention to the changing role of the UN as 1) a diagnostician of the global illness, and 2) a tool for global governance and governance of global commons.

Diagnosing and curing the global illness

An analogy often invoked in discussing the need for efforts like ESD and Sustainability Science is that of physicians. Just as a physician has a vision of a healthy human-being, most ESD and sustainability researchers have a vision of a healthy society and healthy relations between human and earth systems. It is especially telling that the International Commission for Education for Sustainable Development Practice (ICESDP) – launched in 2007 with the support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and tasked to identify practical initiatives to reorient education and training of development professionals – was inspired by the 1910 Flexner Report, which transformed medical education in the United States.1 Based on the recommendations of the ICESDP (2008), the Global Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) was created to offer a two-year degree providing graduate-level students with the skills and knowledge required to better identify and address the global challenges of sustainable development. What motivated John MacArthur to support the ICESPD and the ensuing creation of MDP programmes across the globe was the perceived need to reorient training of development professionals who make decisions about the well-being of millions of people in developing countries.

Physicians seek out knowledge on what needs to be done to allow their patients to attain a vision of a healthy human being. In the same way, sustainability education and sustainability science researchers attempt to produce knowledge that would facilitate attainment of a vision of a sustainable world. The analogy of physicians, however, is in no way new. In ancient Greece, for example, many philosophers saw themselves as analogous to physicians. If physicians treat and heal the body, the role of the philosopher was to provide comparable therapy for the soul to realise human flourishing. What is new today in the early years of the twenty-first century is the diagnosis and proposed remedy of the world we live in. The UN system has long served as the ‘main diagnostician of the global illness of poverty, ecological destruction, human rights violation, and violent conflicts’ (Osseiran and Reardon 1998: 386). The idea for the MDP comes from the US economist Jeffrey Sachs, an architect of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and all the world’s leading development institutions.

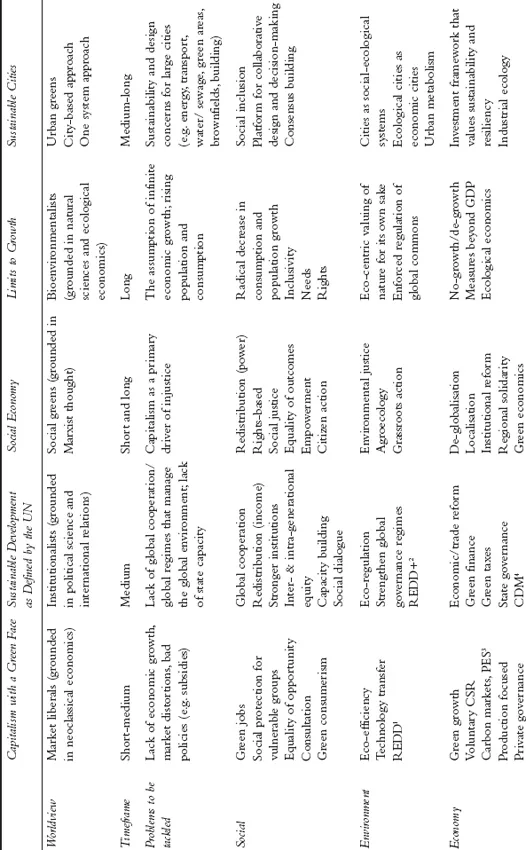

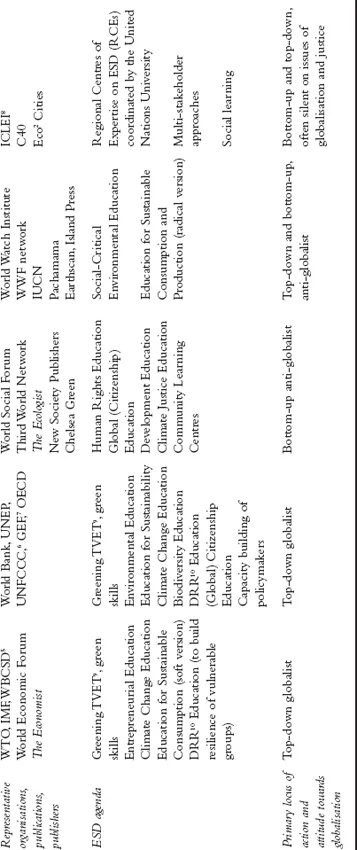

With the target date of MDGs approaching in 2015, the UN Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012 (Rio+20) and the ongoing discussion on the post-MDGs have provided ample opportunities for the UN agencies and other entities such as international NGOs and think tanks to point out the interconnected nature of the global illness and make propositions about how to realise a preferred future – to borrow the title of the Rio+20 outcome document, ‘The Future We Want’. There are diverse visions of preferred futures found in the broad sustainable development community, leading to varied and sometimes irreconcilable views on the nature of interventions required in attaining sustainability (see Table 1.1). Whereas there seems to be an increasing consensus on the need for ‘transformative shifts’ required for realising sustainable development, a proposed cure for the global illness can range from interventions for accelerating economic globalisation to anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation movements. This poses, for example, a question to those who design educational and research programmes in HESD on how to embed equity in the curriculum.

What is rather unique about ESD is that it seems to embrace a whole range of competing worldviews. This is both a strength and weakness of ESD. On the one hand, ESD is open to a diverse array of disciplines and theoretical traditions. On the other hand, ESD lacks a clear definition and there is no consensus on competencies to be fostered through ESD or education for sustainability. For example, Wolbring and Burke (2013), examining the practice and purpose of sustainability-focused education through the lens of ability studies, have concluded that no consensus has been reached within ESD discourses on the process of how to identify essential abilities and a list of such abilities. Whereas there seems to be some shared understanding about sustainability competencies (Mochizuki and Fadeeva 2010; Wiek et al. 2011; Wiek et al. in this Handbook), what is meant by integration of sustainability into the curriculum or the whole institution may be different from one higher education institution to another (for various types of tools for assessing integration of sustainability in higher education institutions, see Yarime and Tanaka 2012).

The MDP degree aspires to integrate the four ‘core areas’ of 1) health sciences, 2) the natural sciences and engineering, 3) the social sciences, and 4) management for sustainable development. On the surface, MDP resonates with ESD and Sustainability Science in that it seeks to foster future leaders who can work flexibly across intellectual, professional and geographic boundaries to contribute to sustainable development. Exposure to a wide range of development problems and different disciplines, however, will not automatically foster the kind of critical and systemic thinking or collaborative skills needed for facilitating a transition to sustainability. While MDP achieves its purpose by solving problems, ESD ultimately ‘achieves its purpose by transforming society’ (UNESCO 2014b: 12). This difference between education for ‘problem solving’ and education for ‘transforming society’ is echoed by a tension between ‘problem solving’ research and ‘world shaping’ research observed by social scientists who aim to enhance the role of the social sciences in integrated research on global environmental change (Crowley 2012). These tensions are expected to continue as the world is not likely to forge a consensus on the diagnosis and cure for the global illness overnight.

Table 1.1 Competing pathways to sustainable development

Source: | The first five columns except for the last two rows have been adapted from UNRISD (2012), which is based on four worldviews put forward by Clapp and Dauvergne (2011). The Sustainable Cities column was added based on Marien (2011). |

Notes: | 1 REDD: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Addressing the science-policy gap and transforming global governance

While a proposed cure for the global illness may range from mild to radical treatment, there is a growing international consensus on the need for taking a more integrated approach to address sustainable development and strengthening the role of the UN system as a diagnostician of the global illness of the twenty-first century. The UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has convened multiple initiatives aimed at a global transition to sustainability in the lead up to Rio+20 and in the ongoing effort to forge an international consensus on the post-2015 agenda. Immediately following Rio+20, Ban Ki-moon established the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), a global network of research centres, universities and businesses led by Jeffrey Sachs and tasked with informing the development of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). He also established the UN Scientific Advisory Board, a board of 26 scientists, including not only natural scientists but also political scientists.2 The Board, inaugurated in January 2014, marked the first time in the history of the UN system that its Secretary-General had a team of chief scientific advisers.

Another example of efforts to enhance an interface between the scientific community and policy makers is the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). IPBES aims at building capacity for and strengthening the use of science in policy making. It can also be considered as an updated science-policy interface compared to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in that it includes capacity building in its mandate. UNESCO works with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and other relevant organisations to operationalise IPBES.

At the same time, international sustainable development research is itself undergoing a major transition. This transformation is being spearheaded by the ten-year research programme Future Earth, which was launched in 2013, integrating the existing four major international research programmes on global environmental change.3 Future Earth aims to provide critical knowledge required for societies to face the challenges posed by global environmental change and to identify opportunities for transformation towards global sustainability (Future Earth 2013). In particular, the mandate of Future Earth includes co-design of research agendas, co-production of knowledge, and co-dissemination of findings and perspectives with key stakeholders, so that scientific knowledge makes an important contribution to decision-making.

While these are promising signs, the problems run deeper than the science-policy links. The inclusion of political scientists in the UN Scientific Advisory Board reflects a growing awareness that the governance arrangements of the twentieth centur...