eBook - ePub

Spain's Civil War

Harry Browne

This is a test

Share book

- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spain's Civil War

Harry Browne

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study offers a succinct analysis of a critical period in Spain's history. It assesses the causes and course of the Civil War and covers Franco's New Spain. For the Second Edition there is a fuller examination of the politics of the Second Republic and the regional and social bases of Spain's political parties. There is also a more detailed account of the military conduct of the war and of the extent of international involvement.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Spain's Civil War an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Spain's Civil War by Harry Browne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia mondiale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MAPS

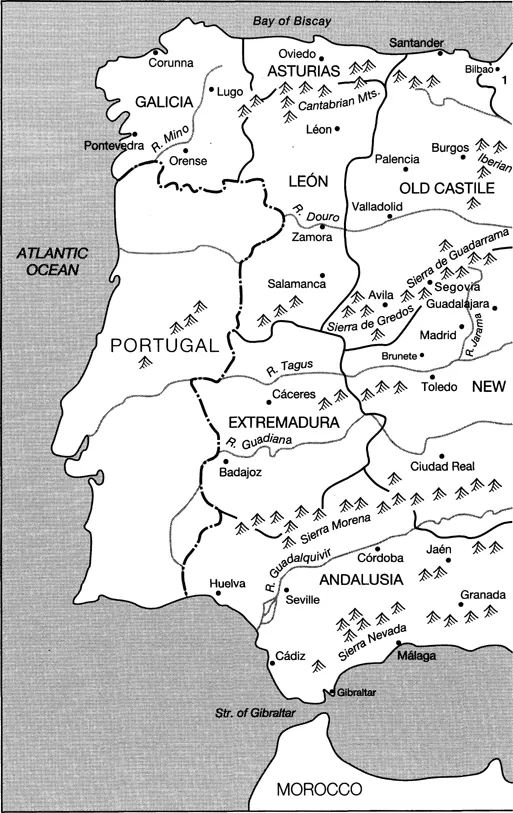

Map 1 Regions and provinces of Spain

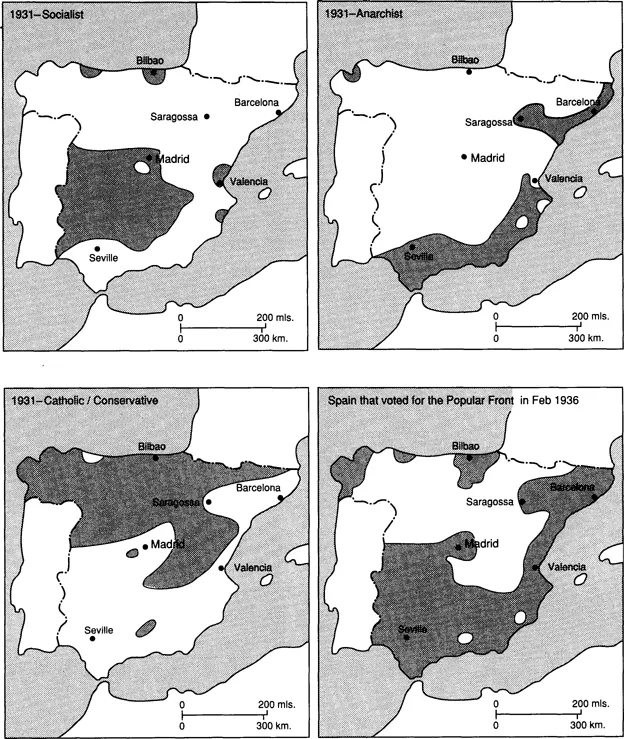

Map 2 Major areas of political affiliation under the Republic

PART ONE: THE BACKGROUND

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, Spain has suffered a series of civil wars of which that of the 1930s – to all outside Spain the Civil War – is the most recent and certainly the most crippling in terms of simple human and material loss. Fundamentally Spanish in origin, these were wars between town and country, between constitutionalists and Carlists, between new and old Spain. Sometimes, as in the wars of the 1830s or 1930s, foreigners were drawn in to what were essentially domestic conflicts between Spaniards with differing visions of Spain. The war of 1936–39 fell within this long, unhappy tradition: it was fought with the ferocity of Carlist* wars, and, on the Nationalist side, with the banners and slogans of Old Castile, defending herself against the new insidious poison of Marxism. The Church and the Catholic middle class fought the war as a crusade against godless ideas threatening the true quality of Spanish life and they rallied enthusiastically behind the army leaders who raised their standard in a traditional pronunciamiento* On both sides the war began with a simple panoply of ideas: defence of the Republic pitted against a call to restore public order. In Europe, the Spanish war was quickly confused with the fascist challenge to democracy, and Spanish problems were interpreted in European terms; yet, in fact, the breakdown had peculiarly Spanish causes. Indeed, it might almost be seen as a consequence of Spain’s failure to become a mature state rather than as evidence of her involvement with the major European conflicts of the 1930s. In the view of one Spanish historian, Carlos Rama [18], the Civil War resulted from Spain’s failure to create a state which could command at least the allegiance, and perhaps even the lukewarm support, of its citizens.

One institution traditionally not offering more than lipservice to the state was the Army, which had seen itself as the quintessence of all that was Spanish, representing – no matter what the political system – the authentic ‘general will’. This conviction that the Army was Spain had been demonstrated at many different times in the nineteenth century, and most recently in 1923, when the Captain General of Catalonia, General Primo de Rivera, had ‘pronounced’ against the parliamentary regime and established the dictadura,* a military autocracy – even though he tried, gradually and unsuccessfully, to edge it back towards a constitutional regime, before finally resigning office in 1930. Within the Army, the most conscious of their role, and the most bitterly critical of parliamentary regimes, were the africanistas,* officers who had served in the residual Spanish empire in Africa. In the 1936 Rising all the leaders were africanistas, and in this sense the rebellion may be seen not only as a military uprising but also as a colonial officers’ coup against their civilian overlords in mainland Spain.

When in 1931 the Army withdrew support from Alfonso XIII, he silently packed his bags and drove off to England and exile [26]. The monarchy, by its link with Primo in 1923, had eroded its own position, and ‘Enlightened’ Spain, the large towns, had declared for the Republican-Socialist alliance in the municipal elections of 12 April 1931. The countryside and the small towns, however, were still overwhelmingly monarchist, which was no good harbinger for the future. In the new Republic the traditional monarchist classes – apart from a minority with the Alfonsist party, the Renovación Española* – backed the opposition Catholic party, the Acción National* (later CEDA*). Monarchism remained in Spain as a force but without an obvious candidate, except amongst Navarrese Carlists who still nostalgically campaigned for the absent Carlos Hugo [29]. The political danger of this passive monarchism lay in its reluctant acceptance of the Second Republic: like the Right in Weimar Germany, the monarchists assumed that Republican Spain would be only an interlude in Spain’s monarchical history.

Within Spain, the position of the Catholic Church had progressively weakened. Until 1808 and the popular revolt against the French invader and ‘el rey intruso’, Joseph, the French-imposed king, the Church had successfully warded off attacks by ministers anxious, under the influence of the Spanish Enlightenment, to bring the Church more firmly under the control of the central government. Ministers and intellectuals [8] had tried to portray the Church as the defender of obscurantism and as largely responsible for the backwardness of Spain. These criticisms became part of the rhetoric deployed by the Cortes of 1812 against the Church, which led to the suppression of the Inquisition and the beginning of an attempt to divest the Church of her land and her wealth. Although the restoration of Ferdinand VII, following the expulsion of Joseph and the French, led to the re-establishment of the privileged status of the Church and the renewal of the Inquisition, increasingly the new liberalism came to dominate the policy of Madrid. In the 1830s a movement initiated by the Liberal Minister Mendizábal led to the expropriation of Church lands. The final outcome of this process was a Concordat between Church and State in 1851 which did at least guarantee priests an income and recognised Catholicism as the religion of Spain.

From this Concordat began, as Gerald Brenan shows [2], that fateful alliance between upper-class Spain and a Church now increasingly dependent upon the rich for additional income, and therefore isolated from the poor in town and country alike. The Church came to be seen as the Church of the wealthy, and the hierarchy as the defender of conservatism of all kinds. In the troubled times of post-First-World-War Spain, the Church offered no guidance, suggested no means by which the extremes of poverty could be reduced, was of the king’s party in the 1920s and, almost without exception, of Franco’s party in 1936. In the crisis of the monarchy, in 1930–31, the Church had withdrawn its support from Alfonso XIII, in common with the established classes and the traditional institutions, but the Church’s attitude to the new Republic was initially no more than neutral, a neutrality which rapidly passed over into active hostility as the liberalism of the Republic’s leaders revealed itself as markedly anti-clerical.

Historically, Spanish liberalism began with an attempt to frame a constitution within a society overrun by the foreigner and long subject to arbitrary government. That first attempt, the Constitution of 1812, gave a model to Europe as well as to Spain and incurred the passionate condemnation of the Spanish Church which identified liberalism with an attack upon itself [3]. The Church’s over-readiness to castigate political liberalism incited in late nineteenth-century Liberals, of whom Manuel Azaña is the outstanding example, an implacable anti-clericalism. Teachers such as Francisco Giner, founder of the Institute of Free Education in 1875, tried to exclude religious influence from education by creating colleges outside the church system; anarchists like Francisco Ferrer, with his Modern School movement in Catalonia in the early 1900s, sought to offer an alternative moral system to that of Catholicism [24]. Church control of education, both in the state-supported primary and secondary schools (more an ideal than a reality) and particularly in the schools of the religious orders, allowed free play for blatantly anti-liberal doctrines. In this control reformers saw the secret of the Church’s hold on Spain. Therefore, when the new Republican government, based upon a Liberal-Socialist alliance, came into office in 1931, it saw its first task as ending the Concordat and removing education from the Church. The Liberals were working within a narrow orthodoxy concerned to bring Spain into the twentieth century, and to create a constitution based upon a modernised society where religion was a matter for the individual and not for the state. The Church reacted to this as an attack upon religion, upon morality, upon the family, upon the traditional Spain by men seized of ideas fostered by freemasons and unbelievers and careless of the fundamental bases of Spanish life [42].

Just as liberalism could be seen as fracturing the mystical unity of Spain, based upon the Catholic Church, so could cultural and political regionalism appear as a threat to Spain’s political unity. Regionalism and localism, the passionate loyalty to birthplace enshrined in the cult of patria chica,* had long been potent forces in Spain, traditions which sprang in part from a long-established anti-centralism and were nourished by the differing languages and histories of Galicia, the Basque Provinces and Catalonia. Basque and Catalan regionalism were also powered by the vital industrial and commercial traditions of these two wealthy regions, both speaking non-Castilian languages. Catalan regionalism had already been granted some recognition by the Mancomunidad of 1913, which grouped together for local government the four principally Catalan provinces of Barcelona, Lérida, Tarragona and Gerona. Under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera in the 1920s, this partial recognition of the strength of Catalan regionalism had been suppressed, the Catalan language banned, and a fresh attempt made to give life to Spanish unity. Catalan cultural and linguistic pride had been severely damaged and political ambitions sharpened when Catalan nationalists framed demands for a separate state within a federated Spain. With the coming of the Republic in 1931, Catalans who had helped topple the monarchy expected political reward for their support. To conservative Spain, this seemed to be confirmation of Catalan egoism, and it was feared that what Catalonia demanded today, Basques and others would want tomorrow [1].

Catalan and Basque aspirations were buttressed by the economic progress which their regions could display. Jordi Nadal [13] has argued that in the nineteenth century Spain in general failed to take advantage of the opportunities for rapid industrial change which were on offer. Certainly, the twentieth-century economic map of Spain showed evidence of what Sánchez-Albornoz [20] has called a ‘dual economy’, with areas of progress such as Catalonia and the Basque Provinces and areas of stagnation such as Andalusia. This dualism extended into agriculture as well as industry, with Valencia diversifying crops and developing citrus fruit production, and parts of Andalusia – Jaén, for example – still maintaining a single-crop economy based upon the olive.

In Catalonia, fundamentally a land of peasant proprietors, a diverse economy had been created, with textiles as the principal industry, but also extending into machine making and the highly profitable activities associated with shipping. Barcelona, the major port of Catalonia, was run by the great families, Catalan industrialists, who looked to capitalist Europe for their model and for their cultural contacts, rather than to Castile. Industrial capitalists in Catalonia had little in common with the agrarian grandees of Castile who lived content with wealth from rents and from unimproved agriculture, based often upon latifundios,* great landed estates with a traditional agriculture failing to provide sufficient food for Spain’s population. These latifundios created vast pools of rural discontent, with labourers living in continual poverty, only partially employed throughout the work year. In rural Spain the contrast between rich and poor was stark; there were no people of the middling sort, few gradations of wealth and class. The new Republic inherited the problems of low agricultural productivity, landless labourers, and impoverished tenants [9; 10].

In agricultural regions such as Andalusia, Bakunin’s anarchism took firm root; land-hungry peasants in the scattered villages of the South heard the promise of the new age which anarchism would bring when the day of revolution finally came [103]. Its shape was clearly defined: there would be a reparto, a redistribution of land; men would be equal; there would be no more grandees, no more priests, no tax gatherers and no civil guards. The means of bringing all this about was ill defined, the tactics shadowy, but come the day – so the anarchists asserted – there would be a spontaneous uprising. This certainty that the millennium would arrive made organisation unnecessary and doctrinally wrong, for each anarchist must be master of himself alone, and of no one else [99; 115; 116].

In Catalonia, in industrialised Barcelona, anarchist doctrines were modified into anarcho-syndicalism, from which developed trade unions with moderates thinking in terms of traditional trade-union objectives: a shorter working day, improved pay, and arbitration committees. On the left, however, classical anarchists were still committed to political strikes and to direct action – murder and robbery – as revolutionary tactics to hasten the birth of the new society. The industrial context of Catalonia, with the small patronal factory employing ten or a dozen men, created networks of working-class relationships profoundly different from the agricultural South and made imperative the discussion of industrial relations and short-term objectives. In Andalusia, on the other hand, anarchist objectives were necessarily long-term, for neither absentee landlords nor bailiffs were susceptible to pressures for improvement.

By 1931 the CNT* – the anarchist federation based in Catalonia and suppressed under Primo de Rivera – had re-emerged as the major left-wing movement in Spain. It was committed to a transformation of society, hostile to the democratic system, unwilling to vote or put forward parliamentary candidates. The tragedy for the Spanish Left was the hold that anarchist doctrines had upon the Spanish working class and the fatal split between the CNT and the socialist trade union (the UGT*) with its bastions of power in Madrid, Bilbao and the Asturias. The PSOE,* the political voice of the UGT, formed part of the Republican ruling coalition, but was numerically weaker than the CNT.

Spain entered the 1930s a backward state, still largely agricultural, with levels of poverty equalled only by other Mediterranean regions such as Greece or Sicily. In politics she was burdened with a newly constructed political system which called for civic loyalties which many Spaniards, deeply localist in sentiment and unused to thinking in broader terms, could in no way ...