![]()

1

Definition and Delimitation

Es irrt der Mensch, so lang’ er strebt.

If you try to better yourself, you’re bound to make the odd mistake.

(Goethe, Prolog im Himmel, Faust Part 1, eds R. Heffner, H. Rehder and W.F. Twaddell. Boston: D.C. Heath and Co., 1954 p. 17)

Human error

Much effort has gone into showing the uniqueness of language to humans: homo sapiens is also homo loquens, and humans’ wisdom is the consequence of their gift of language. Linguistics is, by this fact, the direct study of humankind, and ought to be the most humanistic of all disciplines. Error is likewise unique to humans, who are not only sapiens and loquens, but also homo errans. Not only is to err human, but there is none other than human error: animals and artifacts do not commit errors. And if to err and to speak are each uniquely human, then to err at speaking, or to commit language errors, must mark the very pinnacle of human uniqueness. Language error is the subject of this book. The first thing we need is a provisional definition, just to get us started on what will in fact be an extended definition of our topic. Let’s provisionally define a language error as an unsuccessful bit of language. Imprecise though it sounds, this will suffice for the time being. It will also allow us to define Error Analysis: Error Analysis is the process of determining the incidence, nature, causes and consequences of unsuccessful language. I shall presently return to dissect this definition.

In Chapter 2 we shall explore the scope of Error Analysis (EA) within the many disciplines that have taken on board the notion of error. Indeed, the very idea of ‘discipline’ suggests recognition of the need to eliminate or minimize error. In this book, however, we focus on errors and their analysis in the context of foreign language (FL) and second language (SL or synonymously L2) learning and teaching. Doing this is quite uncontendous: a recent statement implying that error is an observable phenomenon in FL/SL learning that has to be accounted for is Towell and Hawkins: ‘Second language learners stop short of native-like success in a number of areas of the L2 grammar’ (1994: 14). They stop short in two ways: when their FL/SL knowledge becomes fixed or ‘fossilized’, and when they produce errors in their attempts at it. Both of these ways of stopping short add up to failure to achieve native-speaker competence, since, in Chomsky’s words, native speakers (NSs) are people who know their language perfecdy. While we shall focus on FL/SL error, we shall, especially in Chapter 2 which explores the scope – the breadth rather than depth – of EA, refer to errors in other spheres.

In the rest of this chapter we shall attempt to contextualize EA: first, historically, showing the course of development of ideas about learners’ less-than-total success in FL/SL learning; and secondly, by looking at EA as a ‘paradigm’ or approach to a field of study (FL/SL learning) and seeing how that one of several options relates to alternative options. In fact, since paradigms, like fashions, have their heyday in strict succession, any account of them tends also to be historical.

Successive paradigms

Notwithstanding our claim that the study of human error-making in the domain of language Error Analysis is a major component of core linguistics, Error Analysis is a branch not of linguistic theory (or ‘pure’ linguistics) but of applied linguistics. According to Corder’s (1973) account of applied linguistics, there are four ‘orders of application’, only the first two of which will concern us here. The ‘first-order’ application of linguistics is describing language. This is a necessary first step to take before you can move on to the ‘second-order’ application of comparing languages.

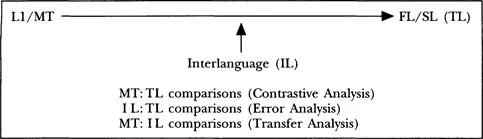

In the applied linguistics of FL/SL learning there are three ‘codes’ or languages to be described. This becomes clear when we describe the typical FL/SL learning situation. In terms of Figure 1.1, at the start of their FL/SL learning, the learners are monoglots, having no knowledge or command of the FL/SL, which is a distant beacon on their linguistic horizon. They start, and tortuously, with frequent backtrackings, false starts and temporary stagnation in the doldrums, gradually move towards their FL/SL goals. This is the complex situation: what are the language codes involved which need to be described?

Figure 1.1 Points of comparison for successive FL learning paradigms

First, language teaching calls for the description of the language to be learnt, the FL/SL. Let us use a term that is neutral between these two: target language or TL. This is a particularly useful label in the way it suggests teleology, in the sense of the learners actually wanting or striving to learn the FL/SL. It may even be extended to include the learners setting themselves goals. Without that willingness, there is of course no learning.

The second code in need of description in the teaching enterprise is the learners’ version of the TL. Teachers are routinely called upon to do this when they decide whether the learners have produced something that is right or wrong. This requires them to describe the learners’ version of TL, or, as it is called by Selinker (1972, 1992), their Interlanguage (IL), a term suggesting the halfway position it holds between knowing and not knowing the TL. Corder (1971) prefers to call it the learners’ idiosyncratic dialect of the TL standard, a label that emphasizes other features it has. Another label that has been applied to description of the learners’ set of TL-oriented repertoires is performance analysis. Færch (1978) attributes to Corder (1975) a conceptual distinction which is relevant here. Performance analysis is ‘the study of the whole performance data from individual learners’ (Corder, 1975: 207), whereas the term EA is reserved for ‘the study of erroneous utterances produced by groups of learners’ (ibid.: 207). Note the consistency in Corder’s equation of performance analysis with the study of the idiosyncratic dialect of each learner. In that case we need to ask what sorts of ‘groups of learners’ develop systems that have something in common. The most obvious group is of learners with a common L1.

There is at least one other language involved in the FL learning operation: the learner’s mother tongue (MT) or L1. This should be described also. I said at least one other language, but there might be more: people who know many languages already might want to learn even more, in which case we should describe the totality of the TL learner’s prior linguistic knowledge, whether this be one or many languages, to varied degrees of mastery.

Moving on to the second-order applications of linguistics, which is comparisons, we can compare these three (MT, IL, TL) pairwise, yielding three paradigms – (a), (b) and (c). By ‘paradigm’ here we mean something like ‘fashion’: the favoured or orthodox way, at a certain period, of viewing an enterprise. The enterprise in this case is FL/SL teaching and learning.

(a) Contrastive Analysis

In the 1950s and 1960s the favoured paradigm for studying FL/SL learning and organizing its teaching was Contrastive Analysis (James, 1980). The procedure involved first describing comparable features of MT and TL (e.g. tense, cooking verbs, consonant clusters, the language of apologizing), and then comparing the forms and resultant meanings across the two languages in order to spot the mismatches that would predictably (with more than chance probability of being right) give rise to interference and error. In this way you could predict or explain, depending on the degree of similarity between MT and TL, up to 30 per cent of the errors that learners would be likely or disposed to make as a result of wrongly transferring L1 systems to L2. By the early 1970s, however, some misgivings about the reliability of Contrastive Analysis (CA) began to be voiced, mainly on account of its association with an outdated model of language description (Structuralism) and a discredited learning theory (Behaviourism). Moreover, many of the predictions of TL learning difficulty formulated on the basis of CA turned out to be either uninformative (teachers had known about these errors already) or inaccurate: errors were predicted that did not materialize in Interlanguage, and errors did show up there that the CA had not predicted. Despite some residual enthusiasm and some attempts to formulate more modest claims for CA (James, 1971), the paradigm was generally jettisoned.

(b) Error Analysis

The next paradigm to replace CA was something that had been around for some time (as we shall presently see): Error Analysis (EA). This paradigm involves first independently or ‘objectively’ describing the learners’ IL (that is, their version of the TL) and the TL itself, followed by a comparison of the two, so as to locate mismatches. The novelty of EA, distinguishing it from CA, was that the mother tongue was not supposed to enter the picture. The claim was made that errors could be fully described in terms of the TL, without the need to refer to the L1 of the learners.

(c) Transfer Analysis

It has, however, proved impossible to deny totally the effects of MT on TL, since they are ubiquitously and patently obvious. Where CA failed was in its claim to be able to predict errors on the basis of compared descriptions. This shortcoming had been noticed by Wardhaugh (1970), who suggested that the CA hypothesis should be thought of as existing in two versions, a ‘strong’ version that claims to be able to predict learning difficulty on the basis of a CA of MT and TL, and a ‘weak’ version that makes the more cautious claim of merely being able to explain (or diagnose) a subset of actually attested errors – those resulting from MT interference. In its strong version, CA is no longer much practised in applied linguistics. This is not surprising, since the alternative, diagnostic CA, is compatible with and easily incorporated into EA, as a way of categorizing those errors that are caused by interference from the MT.

Predictive CA has had to give way to the description and explanation of actually occurring MT transfers. This has led to some contentious relabelling as CA got swept under the carpet, and it is now more politic to talk of ‘crosslinguistic influence’ (Kellerman and Sharwood Smith, 1986) or of ‘language transfer’ (Gass and Selinker, 1983; Odlin, 1989). The term I reserve for this enterprise is transfer analysis (TA) (James, 1990: 207). It must be emphasized, however, that this TA is no longer CA, since the ingredients are different in that when you conduct Transfer Analysis, you are comparing IL with MT and not MT with TL. Nor are you comparing IL and TL, so you are not doing EA proper. TA is a subprocedure applied in the diagnostic phase of doing EA. TA is not a credible alternative paradigm but an ancillary procedure within EA for dealing with those IL:TL discrepancies (and the associated errors) that are assumed to be the results of MT transfer or interference. In so far as TA is something salvaged from CA and added to EA, the balance has shifted.

Interlanguage and the veto on comparison

The third paradigm for the study of FL learning that has been widely embraced is the Interlanguage hypothesis propounded by Selinker (1972). Its distinctiveness lies in its insistence on being wholly descriptive and eschewing comparison. It thus tries to avoid what Bley-Vroman has called ‘the comparative fallacy in FL learner research’, that is ‘the mistake of studying the systematic character of one language by comparing it to another’ (1983: 15). This veto on comparison is probably aimed at CA, but it is not wholly justified. The practitioners of CA similarly stressed the desirability of not allowing the descriptive categories of one language to colour what should be an objective, independent description of another. The idea of describing a learner’s language in its own terms without reliance on the descriptive categories derived from the analysis of another language (the technical term is sui generis) is not new: the Structuralists of the 1950s warned against proscribing sentence-final prepositions in English merely because putting them in this position broke a rule – not of English, but of Latin. There are even echoes of anthropological linguistic fieldwork methods in the comparative prohibition too: study your learner ‘objectively’, much like the anthropological field linguists, missionaries and Bible translators did their native informants.

IL, or what the learner actually says, is only half of the EA equation. Meara (1984) set out to explain why the learning of lexis has been so neglected in IL studies. His diagnosis is illuminating: it is because IL studies have concentrated almost exclusively on the description of ILs, on what Meara refers to as ‘the tools’. And there has been widespread neglect of the comparative dimension. This is regrettable since, ‘we are interested in the difference between the learner’s internalized description of his L2 and the internalized descriptions that native speakers have’ (Meara, 1984: 231). We do have to have a detailed and coherent description of the learners’ repertoires, but we cannot stop there, as Bley-Vroman would have us stop. This is not to say that his directive is misguided: it is necessary to be ‘objective’ and non-derivative in one’s linguistic description, and take care not to describe X in terms of Y. With one exception: when you are doing EA! The reason is obvious. The learners’ errors are a register of their current perspective on the TL.

There is a constant tension between, on the one hand, the long-term descriptive and explanatory priorities of people engaged in IL studies and dedicated to Second Language Research (SLR) and, on the other hand, the shorter-term pedagogic priorities of foreign language educators who do EA. One is tempted at times to conclude that SLR is not a part of applied linguistics, and is not interested in language teaching, but is a branch of pure linguistics, interested in the properties of languages rather than the problems of learners, in language leamability rather than the processes of teaching. There does not have to be tension if we agree that the SLR and EA enterprises are different and have different goals. After all, as Cook puts it: ‘Error Analysis was [and still is! CJ] a methodology for dealing with data, rather than a theory of acquisition’ (1993: 22). Let those who want theory have theory, and those who want them, ways of ‘dealing with data’.

In one sense, however, SLA Interlanguage research is inescapably comparative. There are two ways to conceptualize ‘1Ľ. First, it can refer to the abstraction of learner language, the aggregate of forms, processes and strategies that learners resort to in the course of tackling an additional language. This concept is similar to de Saussure’s langue. Alternatively, ‘IĽ can be used to refer to any one of a number of concretizations (cf. de Saussure’s parole) of the underlying system. These are sequenced in time: IL1 develops after 100 hours of exposure, IL2 after 200 hours, and so on. The SLA researcher who studies IL developmentally or longitudinally, like the historical linguist, will be forced to make comparisons of these successive stages.

In fact, this ‘successive steps’ view of FL learning is not unproblematic for EA as we have defined it. It is plausible to suggest that it has some psychological reality, in that the learners at the learning stage of ILn, shall we say, are in fact aiming at linguistic forms that are not at the end of the IL continuum, not TL forms, but forms that are but one stage nearer to TL than their IL competence is currently located. In that case, we would define errors in terms of the discepancy between what they are aiming at (IL n+1) and ILn, not in tems of ILn and TL as suggested above.

At least one objective observer has no difficulty with the comparative definition of error. John Hawkins could not have been clearer when he stated: ‘The whole concept of error is an intrinsically relational one. A given feature of an [IL] is an error only by comparison with the corresponding TL: seen in its own terms the [IL] is a completely well-formed system’ (1987: 471). There are even times when ...