Why Does Communication “Go Wrong” So Often?

It seems so simple: We say something, and someone else, using presumably the same language as us, receives the message correctly. We take the communication process much for granted in this way, and we get stressed and angry when it doesn’t work like this. By the time we’re done looking at all of the parts of the communication process, you likely will see why it would make more sense for us to be surprised when the process works, as opposed to when it doesn’t work (Richmond & McCroskey, 2009). First, we will define communication. In actuality, there are about as many definitions as there are communication teachers, so I’ll simply pick the one that I think best captures the process, one provided by Richmond and McCroskey (2009, p. 20):

Communication is the process by which one or more people stimulate meaning in the mind of another using verbal and nonverbal messages.

Several aspects of this definition are worth noting. The idea of process is that communication is dynamic and ongoing, meaning that it is continuous, and we are stimulating meaning in others’ minds (and they are stimulating meaning in ours) even when we are not trying to communicate. Suppose you walk into a room to give a presentation. Communication does not start when you start your presentation, it starts as soon as others in the room pay enough attention to you to draw inferences from your behavior, even if you are not verbally communicating with them. At the same time, they may be communicating various messages to you, regardless of whether they are speaking to you. In this sense, communication is an ongoing process.

Notice that we stimulate meaning in others’ minds using both verbal and nonverbal messages. Verbal messages primarily communicate the content dimension of our message, while nonverbal messages communicate the relationship dimension of our message. This relationship dimension is an implied statement of our relationship with the recipient of the message—what we think of the person and of our relationship with him or her. We can communicate warmth and closeness, coldness and distance, or various relational messages in between those two extremes. The relationship dimension is critical because it helps the receiver determine how to interpret the verbal content of our message. And it helps us as communicators by enabling us to tell someone how to interpret the message without spelling it out. Suppose we’re in a meeting and after a colleague proposes an idea, we say “that was interesting.” The verbal aspect of our message is the literal content “that was interesting.” But from the receiver’s perspective, how should that message be interpreted? Was it genuine, sarcastic, dismissive, or something else? In these situations, we do our best to interpret the meaning correctly based on the way the message is delivered non-verbally (or the relational content of the message). Pause for a moment to consider the various ways you could vary your nonverbal behavior when saying “that was interesting” in order to change the relational dimension of the comment. For example, if you sincerely found the idea interesting, how would you deliver the message differently than if you found the idea to be silly and off-the-wall, or if you wanted to be dismissive of the idea? These questions hint at the importance of the relational dimension that is at play each time we communicate. For another perspective on the importance of relational messages, think of a time when you experienced a misunderstanding using electronic communication (email or texting) and had to explain yourself. Unless we use emoticons or spell out how a message should be interpreted, the relational dimension of these messages often is lacking, and that can create problems for us. The same is true when we communicate in-person without carefully considering the relational messages we are sending.

The next aspect of our definition of communication, stimulating meaning, also is important because of the high standard we have to achieve to truly communicate. It is not enough to talk, we also must make sure we are heard and understood. It’s not what we say, it’s what the other person hears. In other words, if we have not stimulated the desired meaning in another person’s mind, then we are doing little more than blowing hot air. If we focus only on what we have to say, our focus is on talking. To communicate effectively, we instead need to focus on the meanings other people are gaining from our verbal and nonverbal messages. This is challenging because meanings for words reside within people. If 20 different people read or hear the word “fun,” each of those people may have a different meaning for “fun” in their minds. We have to take this into account when we are trying to stimulate our meanings in another person’s mind, and use terms that will be meaningful to the other person, regardless of what they mean to us.

And here is where we begin to see why there might be communication problems in the workplace (or elsewhere). Let’s take a fairly simple example, making a request. Say that you are a supervisor in a retail store and you tell a subordinate to “take care of a customer” who is in another section of the store, and appears to be in need of assistance. In your mind, “take care of the customer” really means “do anything that is needed to make sure the customer has a great experience on your watch, and comes back again.” But the meaning in your subordinate’s mind is different. To your subordinate, “take care of the customer” may mean as little as “ask the person if help is needed, answer questions, and ring the customer up.” This difference may end up mattering little, but it could be important if the customer needs the kind of help that requires the subordinate to exercise ambition or initiative. For example, you may have had the experience of going into a store looking for a something important, only to find that it wasn’t available. This nonavailability can be communicated in a variety of ways. Unfortunately, it may be communicated with an indifferent “no we don’t have that” or “it’s out of stock,” with little additional information. Say you encountered this response from the subordinate above. It’s frustrating because you have to ask a string of follow-up questions to get any useful information from the employee (“When will it be back in stock?” “Can you do anything else to locate it?” “Would another store have it?”). But … from the employee’s perspective, he or she “took care of the customer,” and therefore, honored the supervisor’s wishes.

So to recap, you gave a simple command to a subordinate, not involving any complex language, yet it is clear to you that the subordinate did not follow through on your wishes to “take care of the customer.” It is an example of failing to stimulate the desired meaning in the mind of the employee. In this case, it happened because the two of you had different meanings for “take care of the customer.” This is just one of the many ways we can experience a failure to communicate successfully with someone. Below I outline a model of communication, and in each element of the model, there is potential for the communication process to be disrupted.

A Model of Communication (and All That Can Go Wrong When We Communicate!)

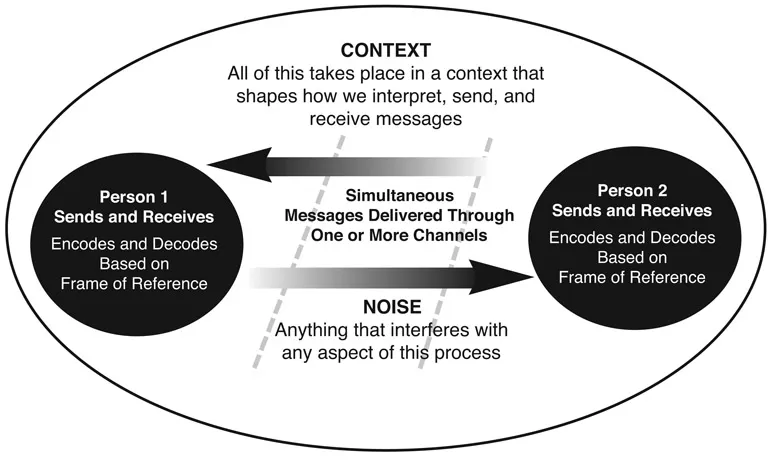

Figure 1.1 Model of Interpersonal Communication

The model I am about to cover (see Figure 1.1) is in most communication textbooks, and it is covered during the first week of many communication courses. To be honest, I used to find it tedious to teach it. But over the years I’ve come to appreciate the model as a blueprint of everything that has to go right in order for us to be able to communicate successfully. From this perspective, it is much more fascinating, because several things have to happen to enable successful communication. And yet every day, without thinking about it or noticing it, these things do happen, almost instantaneously, and we do succeed. This is impressive. Still, the failures we encounter are highly frustrating and often costly, so it is worth our time to explore the many ways in which a problem with one or more parts of the process help lead to disrupted communication.

The Communicators. The communication process involves individuals who simultaneously send and receive messages. Sending messages involves a process known as encoding, and receiving messages involves a process known as decoding. Encoding involves taking the meaning we want to convey and putting it into the form of a message (involving both verbal and nonverbal aspects) that will help us accomplish our goal. Although we typically don’t consciously think about the encoding process, we actually make a number of important decisions when encoding. We consider our goal and determine what words to use and when to use them, and we determine how we will deliver the message nonverbally (which means determining expressions, gestures, posture, vocal tone, pauses, and several other nonverbal cues). Again, while we likely have thought very carefully about these decisions when we had to deliver very important messages, most of the time we do this “on-the-fly,” without consciously thinking about each of these elements of encoding.

Decoding involves similar procedures, also typically performed with little conscious awareness. We receive a message from someone and have to decide what it means. This involves considering the literal verbal content, and also any relational cues that accompany it (in other words, the content and relational elements of the message). We have to use the other person’s expression, posture, gestures, vocal tone, and so on to correctly infer meaning from his or her message. As with encoding, we typically do this very quickly with little conscious awareness (unless the occasion motivates or requires us to be more deliberate in decoding the message). At the heart of both the encoding and decoding processes is the need to bridge the gap between the meaning that is in our own minds and the meaning in the minds of others. For example, the meaning of “communication” in my mind is different than the meaning of “communication” in your mind. So as I encode my thoughts into messages in each chapter, I continually have to consider the gap between our meanings, and how I best can bridge it. This is no different than when each of us communicates with others each day. The gap that I keep referring to exists because we each approach communication situations with a different frame of reference.

Our frame of reference is the perspective we bring to a communication situation. It is unique to us and continually evolving, as it has been informed by our personality, self-concept, and the accumulation of our own life experiences. It includes our thoughts, values, attitudes, expectations, and so on. Nobody has a frame of reference that is identical to our own, so the challenge of encoding is to package the meaning in our minds in a way that will successfully stimulate the desired meaning in the mind of a person whose frame of reference is different from our own. This is why communication experts continually stress the importance of being other-oriented, or of being sensitive to our listener’s perspective, so we better can reach her and stimulate meaning in her mind. The better we consider our desired audience and their frame of reference, the better we can tailor the message to them and succeed in accomplishing our communication goal. The significance of being other-oriented becomes more clear when we consider our experiences as listeners. Just consider a time when a physician’s message either succeeded or failed in fitting your frame of reference. In the latter case, the physician may have talked “above” by using confusing terminology, and possibly delivering the message too quickly. Examples like this, in which a communicator fails to tailor a message to the listener’s frame of reference, can be very frustrating for listeners. To better understand frames of reference, we will examine an important element that helps shape our frames of reference: schemas.

A schema is the framework that helps us organize our knowledge. Schemas can be thought of as sort of mental “filing cabinets” that are organized in a way to help us access concepts. We have many schemas, and each schema is a cluster of information that is related to a particular concept. For example, consider your schema for the concept of “football.” Readers who know little about football will have little to no schema for the concept. Those who know a great deal about football will have a complex and detailed schema. It likely will include several subcategories, for concepts such as famous players, different offensive and defensive formations, types of plays, the various positions on each team, memorable games and plays, statistics (of both team and individual players), different teams, the rules, and so on. Notice that most of these subcategories could have subcategories of their own. For example, the category of “types of plays” can be broken down into numerous categories based on what type of play is best for what type of game situation. If you think of your own areas of interest (maybe music, literature, television, a different sport, your job), you can begin to think of how your knowledge of these areas is organized into various schemas. One of the goals of this book actually is to help you develop your schema for interpersonal communication in the workplace.

The concept of schema becomes important when we consider the role that schemas play in the communication process. Consider the football example above. Imagine you are in a conversation with two people about football, Casey, who has a very well-developed schema for football, and Pat, who has little to no schema for it (assume you have a well-developed schema for football). How will they respond differently, based on their schemas for the topic? As you use football terminology, Casey will be able to “fit” what you are saying into the well-developed schema. Casey will be able to follow you and converse on the topic without too much effort. However, your terminology will be “above Pat’s head,” as Pat has no schema to enable recognition of the football terminology you are using. Thanks to this absence of schema, as far as Pat is concerned, you might as well be speaking a different language. Casey will be more likely to remember what you said (as it will be easy to fit into the existing schema), while Pat will be less likely to remember, unless he devotes effort to learning the terminology you are using, and how it fits together, so that he can begin building his own schema for football. And this brings us back to the important challenge of tailoring our messages to the listener’s frame of reference. If we want our listeners to accurately interpret and remember what we are saying, we should try to use terminology that they can incorporate into their existing schema, or if they lack a schema, we should try to “attach” our information to schema that they already possess. For example, if we were discussing football with Pat (who has little to no schema for it) and wanted him to better understand the concept, we should explain or discuss football in terms that Pat will understand (because he has a schema for them). In other words, we would use analogies, metaphors, or examples to link new concepts to Pat’s existing schema. We could start simple, by explaining some of the positions, rules, and objectives, and then build from there. Conversely, with Casey we should expect to use football terminology, as we otherwise would be “dumbing” it down to someone with such a well-developed football schema. The trick is to make sure we are communicating in a way that complements our listener’s schema.

The above examples demonstrate the role our frame of reference plays in the encoding and decoding processes. To the extent our frame of reference overlaps with that of the listener, we will have more common ground and in some ways it will be easier to stimulate the desired meaning in the listener’s mind. And if we lack that common ground (overlap in frame of reference), it will take more effort to tailor our message so that it fits our listener’s frame of reference.

The Message and Channel. The meaning we wish to convey to our listener is delivered in the form of our message. As mentioned, it contains both verbal and nonverbal components, and communicates both content and a sense of our relationship with the listener. The message is delivered via a particular channel. Common channels include face-to-face, phone, email, text messages, video conferencing, among others. Note the different ways in which our choice of channel can influence the process of communication. There are aspects of channels that can make it more or less difficult to communicate with others, and each channel has its own quirks. In addition, it is worth considering the match between the message we’re trying to send and the channel we use, as certain channels may be a better fit for certain types of messages.

Noise. Noise is anything that interferes with the message we are trying to send, and may be physical or psychological in nature. Physical noise is anything external to us that interferes with the message. It could be actual noise (a coworker’s music, construction outside, etc.) or a function of the channel we choose (static on a phone line, delays in web or video conferencing). A newer type of physical noise comes in the form of text messages people get while they already are communicating with someone (such as when students text during class, or employees text during important meetings). When we communicate and want to receive what the other person is saying, it is important to do what we can to eliminate physical noise.

But even if we eliminate any physical noise, it is much more difficult to address any psychological noise that might be present in the situation. Psychological noise is internal within us, and may include our mood, physiological state (we may be too tired or too hungry to pay attention to someone), emotions we are experiencing, our own attitudes about the subject or the person with whom we are talking, or other thoughts or feelings that might distract us or prevent us from paying attention. This helps explain why it is difficult to communicate ...