![]()

1. An Introduction to Human Evolution, and the Place of the Pontnewydd Cave Human Fossils

Chris Stringer

The earliest stages of human evolution took place in Africa between about 7 million and 2 million years ago, and it was there that typical hominin features such as bipedalism, canine reduction, carnivory and stone tool technology had their beginnings. The term hominin refers to the lineage of human and human-like species post-dating our divergence from the lineage of our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees. Genetic data suggest that the human lineage diverged from that of chimpanzees around 6 million years ago, but until recently there was little relevant fossil evidence from this time period. Now, with the finds of Ardipithecus from Ethiopia, Orrorin from Kenya, and Sahelanthropus from Chad, we have material that may lie close to the ultimate origins of humanity. However, it is not yet clear how these finds relate to humans, chimpanzees, and to each other, and it is not until about 4 million years ago, with the appearance of australopithecines (‘Southern apes’), that the picture becomes somewhat clearer (Wood and Lonergan 2008; Klein 2009; Stringer and Andrews 2011).

At least eight species of australopithecines are now known, stretching from Chad and Ethiopia to the location of the first discoveries, South Africa. These different species are sometimes grouped into ‘gracile’ and ‘robust’ forms, with the latter showing a range of specializations, especially in powerful jaws and enlarged molar teeth. Some experts prefer to formalize this distinction by grouping the gracile species in the genus Australopithecus, and the robust forms into the separate genus Paranthropus (‘Beside humans’). Even though it is known from fossils and ancient tracks that the australopithecines were bipedal, like humans, they still showed many skeletal differences from us, and hence they are not usually regarded as true humans – that is, members of our genus, Homo. For that status, a brain size above the 350–550 millilitre volume of australopithecines and modern African apes would be expected, along with features such as a less projecting face, a more prominent nose, smaller teeth, and a human-like body shape. Where it could be determined, it might also be expected that other human features such as regular tool production, high levels of carnivory, and a relatively long period of growth and development, might be present. For the australopithecines, these human features cannot definitely be recognized. But while the last australopithecines still lived in southern and eastern Africa, more advanced hominins had appeared and were living alongside them; these are usually regarded as the first humans and are often assigned to the species Homo habilis (‘Handy Man’).

By about 2.3 million years ago, these new types of hominin had appeared in the fossil record of eastern and southern Africa. The finds are isolated and rather incomplete, but include a lower jaw from Uraha in Malawi, the side of a cranium from Chemeron in Kenya, and an upper jaw from Hadar in Ethiopia. At the slightly earlier date of about 2.5 million years ago, the first recognized stone tools were being manufactured, and these evolutionary and behavioural events may have marked the advent of the earliest true humans, who are often assigned to the species Homo habilis. This member of the genus Homo was named in 1964 by Louis Leakey and colleagues on the basis of fossils found at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, now known to date to between 1.5 and 1.8 million years ago. Homo habilis was regarded as intermediate between australopithecines and later humans, and fragments of skull were used to estimate a brain size of about 700 millilitres, above the values for australopithecines and the largest-brained apes. The back teeth were large, but narrow, compared with those of earlier hominins. Further material attributed to Homo habilis has been recovered from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya and neighbouring areas since 1969. These include a number of partial skulls, mandibles, and, from the same sites, a hip bone and various limb bones. In addition, there were simple stone tools, all dating from the period between about 1.5 and 2.0 million years ago. The specimens are generally known from their Kenya National Museum catalogue numbers, and the initials of the original site name, East Rudolf (later renamed East Turkana).

Probably the most famous of these fossils is KNM-ER 1470, found in 1972. This skull had a large brain (volume about 750 millilitres) and was originally dated to more than 2.5 million years ago, subsequently revised to about 1.9 million years. The braincase had a more human shape than is found in australopithecines, but the face was flat and very high, with prominent and wide australopithecinelike cheekbones. Although no teeth were preserved, the spaces for them were large by human standards. There are correspondingly large jaws and teeth in other specimens from the same levels at Koobi Fora, and some skull fragments indicate an even larger brain than in KNM-ER 1470. If hip and leg bones found in the same deposits belong to the species, they indicate that some of these very early humans were large and apparently rather similar to the later species Homo erectus in aspects of their body structure. The specimens from Koobi Fora discussed so far have often been assigned to Homo habilis. However, there are further finds from Koobi Fora that complicate the picture of early human evolution. These include specimen KNM-ER 1813, a small skull with a brain volume of only 510 millilitres, which nevertheless looks more ‘human’ in its face and upper jaw than does the 1470 skull, and KNM-ER 1805, which has teeth like 1813, a face more like 1470, a brain capacity of about 580 millilitres, and a braincase with a primitive crest along the midline – a feature otherwise only found in large australopithecines among early hominins. The meaning of this great variation in morphology is still unclear, but it may be that Homo habilis was not the only human-like inhabitant of eastern and southern Africa about 2 million years ago.

Further evidence of this complexity has come from a subsequent discovery at Olduvai of parts of a skull and a skeleton of a small-bodied hominin (OH 62) from the lowest levels, which had previously yielded Homo habilis fossils. Features of the fragmentary skull are similar to those of some Homo habilis fossils, yet the rest of the skeleton more closely resembles those of much more ancient australopithecines. While some experts still believe that Homo habilis had a very variable body size, it now seems more likely that there were at least two forms of early Homo, one large and the other small, with the small species retaining australopithecine features in the limbs. One suggestion is that the large forms, such as 1470, represent a distinct species, Homo rudolfensis, while the smaller ones would still be classified in the original species, Homo habilis. If this view is accepted, the oldest finds mentioned, from Uraha and Chemeron, would represent Homo rudolfensis, while the Hadar upper jaw would be a genuine habilis (Wood and Lonergan 2008).

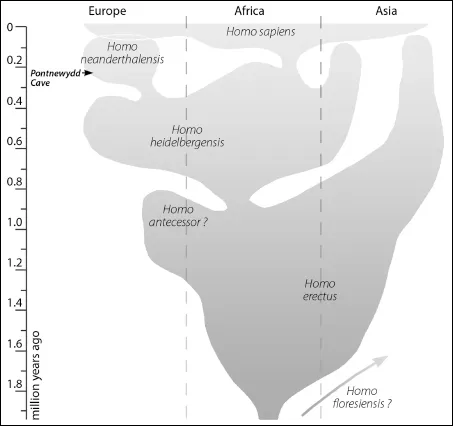

However, although many experts regard the Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis fossils as belonging to the genus Homo, they still lacked several ‘human’ features. These include our distinctive long-legged and linear body shape, an extension of childhood growth and development, and higher levels of encephalization (enlargement of brain relative to body size). These only really become evident around 1.8 million years ago, and are manifested in the species Homo erectus (‘Erect Man’). This species is currently first recognized in the fossil record of eastern Africa, and it persisted for well over a million years in some parts of the world. Homo erectus was the first human species known to have spread out of Africa to Asia (although Homo floresiensis, discussed below, may provide evidence of an even earlier dispersal) (Figure 1.1). Most scientists believe that the African and Asian fossils assigned to Homo erectus represent a single species, but a minority feel that the earliest African fossils represent a more primitive, and presumably ancestral, species called Homo ergaster (Wood and Lonergan 2008; Klein 2009; Stringer and Andrews 2011).

If we accept the majority view, early examples of Homo erectus are known from northern Kenya, on the east side (Koobi Fora and Ileret) and west side (Nariokotome) of Lake Turkana. At the eastern sites skulls (e.g. KNM-ER 3733, 3883 and 42700) and various other fragments have been found, while at Nariokotome the nearly complete skeleton of a boy (KNM-WT 15000) was discovered in 1984. These fossils are characterized by brain sizes of some 700–900 millilitres (averaging well above those of earlier African fossils), but the braincase was relatively long, flattened, and angular. The brow ridges were prominent, whilst the face was less projecting than in earlier humanlike species, with evidence of a more prominent nose (another typical human feature). The Nariokotome boy’s skeleton shows that although he was only about 9 years old at death, he was already about 168 centimetres (5 ft 6 in.) tall and well built. He had the long-legged but narrowbodied build found in many of today’s tropical humans, but there were also some unusual features in his spinal column and rib cage. Nevertheless, his skeleton below the neck was unmistakably that of a human.

Other examples of early Homo erectus are known from Olduvai Gorge, where a skull dated to about 1.2 million years ago was discovered in 1960. This strongly built skull (OH 9) has a brain volume of about 1,050 millilitres, a flat forehead, and a very thick brow ridge. Later finds from Olduvai (less than 1 million years old) include jaw fragments, a robustly built hip bone and partial thigh bone (OH 28), and a small and more lightly built skull (OH 12), which represents either an extreme variant of the Homo erectus type or perhaps even an entirely separate species. Elsewhere in Africa, fossils attributed to Homo erectus have been found in Kenya (e.g. Baringo), and further afield at localities such as Buia (Eritrea), Algeria (Tighenif), Morocco (e.g. Aïn Marouf and the Thomas quarries), Ethiopia (e.g. Daka and Melka Kontoure), and South Africa (e.g. Swartkrans).

By 1.6 million years ago, Homo erectus was also present in western and eastern Asia, with particularly rich finds dating from about 1.75 million years ago from Dmanisi in Georgia (Rightmire et al. 2006; Lordkipanidze et al. 2007). These latter specimens are primitive and varied enough to raise fundamental issues about the origins of the species. Some researchers have even used them and the enigmatic fossil material assigned to Homo floresiensis, from Liang Bua, on the Indonesian island of Flores, to question the orthodox view that Homo erectus originated in Africa and dispersed from there. Instead, they have argued that a more primitive human or even pre-human species emerged from Africa before 2 million years ago, and evolved in Asia to give rise to the Dmanisi people, the Homo erectus populations of the Far East, and the Flores hominins. Some groups then re-entered Africa and evolved into the later forms of humans known from that continent.

Figure 1.1. A representation of the later stages of human evolution out of Africa and into Asia and Europe. We now know there was an additional Asian descendant population of Homo heidelbergensis, known as the ‘Denisovans’.

The East Asian populations are best known from the finds of ‘Java Man’ in the 1890s and ‘Peking Man’ in the 1930s, although many additional finds have since been made in both Indonesia and China. The Javanese finds are generally earlier in date, and more robust, with relatively small brain volumes, although there is also an enigmatic sample of shin bones and skulls, lacking faces, from Ngandong (Solo) in Java, which may represent a late-surviving descendant form. The East Asian finds show general differences from the African fossils of Homo erectus; the skulls are often more strongly reinforced with ridges of bone, and the walls of the skulls are generally thicker. The fragmentary bones of the rest of the skeleton known from Zhoukoudian (the ‘Peking Man’ cave site) are strongly built, like their equivalents from Africa. One of the thigh bones found in the Javanese excavations in the 1890s looks rather more modern and research suggests that it may be geologically younger than the Homo erectus skulls.

Information about the way of life of Homo erectus has been gathered from both caves and open sites. The early African and the Asian representatives used flake tools manufactured from local materials such as lava, flint, and quartz, but from about 1.5 million years ago African groups produced larger, bifacially worked tools, such as handaxes and cleavers. These were also used by post-Homo erectus peoples in Europe and western Asia from at least 500,000 years ago. The Homo erectus peoples were nomadic hunters and gatherers, although living more simply and opportunistically than any hunter-gatherers alive today. Their teeth were similar to our own, albeit larger, and indicate a mixed diet of meat and plant foods.

Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis

We now know from archaeological evidence that southern Europe was populated around 1.5 million years ago, not long after the time of the Dmanisi site in Georgia. Fossil human remains that may represent these early Europeans are known from Sima del Elefante and Gran Dolina, part of the Atapuerca complex of sites in northern Spain. The oldest material, from Elefante, consists of the front part of a jawbone and a hand bone, dated at about 1.2 million years old. The somewhat more complete material from Gran Dolina dated to about 800,000 years, has been assigned to a new human species called Homo antecessor (‘Pioneer Man’), characterized by a combination of primitive features found in early Homo fossils from Africa and Dmanisi, and some more derived features also found in Chinese Homo (Bermúdez de Castro et al. 2008; Carbonell et al. 2008). The earliest occupation of northern Europe, recorded archaeologically at East Anglian sites such as Pakefield and Happisburgh (Parfitt et al. 2005; 2010; Stringer 2007; 2010), overlaps the time-frame of Homo antecessor, and it may well have been this species which undertook the first colonizations of Europe at higher latitudes.

By about 600,000 years ago, another human species had appeared: Homo heidelbergensis. The applicable fossil remains have sometimes been known by the unsatisfactory term ‘archaic Homo sapiens’ (implying that they belong to the same species as modern humans), but it seems more appropriate to regard them as a distinct species, one which has been named after the 1907 discovery of a lower jaw at Mauer, near Heidelberg, Germany (Stringer 2002). This species had a larger average brain size (around 1,100–1,300 millilitres in volume) than Homo erectus, with a taller, parallel-sided braincase. There were also reductions in the reinforcements of the skull and in the projection of the face in front of the braincase, an increase in the prominence of the face around the nose, and changes in the base of the skull that might indicate the presence of a vocal apparatus of more modern type. The rest of the skeleton is not so well represented in the fossil record (e.g. there are disparate bones from Broken Hill in Zambia, and a partial tibia from Boxgrove in Sussex, England), but what evidence there is suggests that Homo heidelbergensis was at least as strongly built in the body as was Homo erectus.

It is not generally agreed which particular fossils from 250,000 to 600,000 years ago actually represent Homo heidelbergensis, although African specimens such as the material from Broken Hill or Kabwe (Zambia), Elandsfontein (South Africa) and Bodo (Ethiopia) are usually included by those who accept that Homo heidelbergensis extended outside of Europe. Similarly, in Europe, there has been dispute about whether the fossils from Mauer (Germany), Vértesszöllös (Hungary), Petralona (Greece), Bilzingsleben (Germany), and Boxgrove (England) represent ‘advanced’ Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or ancestral Neanderthals. It appears that Homo erectus persisted in the Far East until at least 400,000 years ago, and the Ngandong (Solo) remains from Java may be as young as 50,000 years. However, in China there is evidence that after 400,000 years Homo erectus was succeeded by more derived populations exemplified by the skull from Dali, and the partial skeleton from Jinniushan, which might represent a new species, or even local examples of Homo heidelbergensis. There is a comparable partial skull from deposits of the Narmada River in western India, which is similarly difficult to classify. These Asian specimens may eventually turn out to be examples of the population known as ‘Denisovans’, identified from distinctive ancient DNA in fragmentary fossils from Denisova Cave, Siberia (Stringer 2011).

Neanderthals and Modern Humans

By about 400,000 years ago, further evolutionary changes in Homo heidelbergensis led to the differentiation of a distinct lineage in Europe: that of the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). Early examples are recognized from sites such as Swanscombe (England), Atapuerca Sima de los Huesos (Spain), and Ehringsdorf (Germany), and indeed evolutionary continuity is such that there are disputes about whether the Sima material might alternatively represent a late form of Homo heidelbergensis (some dating of the Sima material would place the fossils at more than 530,000 years old (Bischoff et al. 2007)). By 130,000 years ago, the late Neanderthals had evolved, characterized by large brains housed in a long and low braincase, with their distinctive faces, dominated by an enormous and projecting nose. The most characteristic Neanderthals were European, but closely related peoples lived in Asia, as far east as Uzbekistan and even (using DNA evidence from fragmentary fossils) southern Siberia, and in Iraq, Syria and Israel. The physique of the Neanderthals seems to have been suited to the conditions of Ice Age Europe, yet by about 30,000 years ago they had apparently become physically extinct over their whole range. However, genomic reconstructions of their DNA suggest that this still survives in Eurasian populations today, as a result of at least isolated occurrences of ancient interbreeding (Stringer 2011).

The disappearance of the Neanderthals from Europe and Asia may have had much to do with the arrival of early modern people (Homo sapiens), who potentially competed with them for the available resources, and growing ...