![]()

1

The Global Climate Change Policy Environment

The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.

UNFCCC 1992: Article 2

This chapter presents an overview of the global climate change protection framework noting when and how gender considerations have entered. It also explores the scientific imperative behind the UNFCCC and discusses in brief the economic and political under-currents that have brought that process to a log-jam over the last 7 years.

It is undeniable. The evidence is unequivocal. At the planetary level, global temperature and the atmospheric concentration of GHGs is rising. This is causing specific kinds of impacts at global, regional, national and local levels posing wide ranging challenges for human beings, animals and plants.1 These specific climate variability impacts include alterations in rainfall patterns and consequent storms, floods or droughts in different parts of the world. Adverse impacts on natural ecosystem, agriculture and food production, human health and limited access and availability to water are already being felt by millions of girls, boys, women and men in the developing countries of Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Climate change is driving the occurrence of more frequent storms such as super storm Sandy, typhoon Haiyan and rising sea levels. Super storm Sandy devastated the New York City area in 2012. Typhoon Bopha, also in 2012, killed more than 1,000 persons in the Philippines. It was followed the next year by Haiyan (Yolanda) which waged havoc in South East Asia and yet again ‘devastated the Philippines’. According to The Economist, Haiyan, which was one of the worst storms ever recorded, created about $15 billion dollars’ worth of damages (The Economist 2013). Rising sea levels, predicted to reach as much as 23 inches by 2100, will cause shore lines to move further inland posing danger to highly populated cities in a number of developing countries, such as Mexico, Venezuela, India, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Vietnam, as well as, play havoc on the lives of millions of women, men and children living in all small island states and the river delta regions of the world (World Bank 2012a).

The anthropogenic climate change (ACC) tenet outlined by the IPCC in its Fourth Assessment Report (2007) is well supported by the latest findings of the scientific community. Scientific research now more clearly show the link between extreme weather and man-made GHGs (IPCC 2012, 2013). Earth scientists, climate scientists, meteorologists and oceanographers all have expressed high levels of certainty about the basics of climate change and human activity as a primary driver.2 While there remains uncertainty about how particular aspects of climate change (for example, changes in cloud cover, the timing or magnitude of droughts and floods) will unfold in the future,3 by 2011 at least 34 national academies of science such as those in the major G8 countries, plus Brazil, China and India and Poland have made formal declarations or statements supporting the view that global warming is real and almost certainly caused by human activities. This consensus on global warming and its human causation has been long in the making. It is ultimately one of the key driving force behind the continuing, though political fraught and economically challenging, global effort to build a strong and effective global climate protection regime.

This chapter undertakes a forensic analysis of this global climate protection effort. The next section traces the evolution of the international environment and climate protection architecture which has been emerging in its contemporary form since the 1970s. The subsequent section presents an overview of the outcomes of climate negotiations, undertaken by a group of over 194 countries since 1992, under the umbrella of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC is currently the only legal framework responsible for the formation and implementation of climate protection policies on a global scale.

The chapter also explores how gender and other equity issues have been integrated into the policies, programmes, instruments and mechanisms of this global climate protection regime, focusing on the different turns and twists of the attempts by gender advocates to integrate gender equality concerns within the overarching structural framework of the UNFCCC. The remaining four sections of the chapter briefly discuss some of the key issues that challenge the global protection regime. These inextricably intertwined and challenging undertows that sometimes seems to cripple the global awareness and willingness to tackle the drivers of climate change are the economics of climate change and the tumultuous politics of climate change negotiations. The chapter also briefly explores the role of climate science in shaping the contours of the global climate protection. Chapter 2 will bring these strands together in a focused discussion of the fundamental debate about equity, fairness and climate justice in the global climate change regime. It will also highlight the debates on the critical gaps (development, emissions and fairness/ equity, adaptation and finance) that are seemingly hamstringing the current negotiation process.

1.1 The evolution of the international environment and climate protection architecture

Since at least the 1970s, the global community has recognized the critical and far reaching dangerous interactions between human activities and the earth’s atmosphere. Environmental activists, scientists and policymakers have since worked to raise global awareness of the environmental and ecological challenges posing danger for the earth’s biological and physical systems that support life. The initial thrust of environmental activism on a global scale focused on air, water and marine pollution and the conservation and preservation of biological diversity and non-renewable resources that enable ecological cycles and all human activities.

In the early 1970s a number of international conferences were convened on environmental issues geared towards developing a global consensus on the nature of the problems and to set up agreed frameworks for policy solutions (please see Appendix 1.1 for more details). Many of these early events were scientific and expert gatherings focused on examining the nature and processes of erratic weather patterns, the nature of environmental degradation and the consequent endangerment or near extinction of some species (such as amphibians, birds and tree snails)4 and the using up of non-renewable resources (such as peat and minerals). Such meetings, which also attracted policy makers and environmental activists, highlighted the urgent need to deal with the effects of human activities on wetlands, marine eco-systems as well as climate factors impacting temperature, soil and humidity and desertification. These meetings helped to define and further clarify the elements that would be needed for ensuring sustainability and thus set the groundwork for high level political discussions that would culminate in the creation of a number of multilateral and plurilateral environmental agreements such as the Montreal Protocol, the Convention on Biodiversity and the UNFCCC. These agreements are now the bedrock of global environmental governance.

The first two major summit level international conferences on environment were the UN Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm, 1972) and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED, the Earth Summit or the Rio Summit, 1992). The Stockholm Declaration on the human environment emphasized the shared responsibility for the quality of the environment, especially the oceans and the atmosphere. It made over 200 recommendations for international level actions on matters ranging from climate change, marine pollution and toxic waste focused on the management of the biosphere. Stockholm also set in motion processes that laid the foundation of modern environmental regulation, including the creation of a global environmental assessment programme (Earthwatch) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Twenty years later the more politically oriented 1992 UNCED, which focused on the theme of environment and sustainable development, culminated in three signature pieces of environmental landmarks: the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the Statement of Forest Principles and an ambitious action plan for catalysing and stimulating local, national, regional and international cooperation in addressing environmental degradation, Agenda 21. It also facilitated the signing of three multilateral environmental agreements that were negotiated on parallel tracks prior to and during the conference planning processes. These so-called Rio Conventions are the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Convention on Com batting and Controlling Desertification and the UNFCCC. Ten years after UNCED, the 2002 Johannesburg Conference sought to enhance and enlarge the operational domain of Agenda 21, the UN programme of actions from Rio, by proposing concrete steps and identifiable quantitative targets under the Johannes burg Plan of Implementation.

During the period of the 1970s to the 1990s a number of critically important international instruments and international and national institutions were set up to ground environmental protection policy globally and nationally. For example, in 1970, the US established the Environmental protection Agency and the European Union (formerly European Economic Community) also established an Environment and Consumer Protection Service (1973). Internationally, in 1972, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)5 was established to perform both the normative role of assessing global environmental state, facilitate international environmental policy development and formulate multilateral environmental agreement in the context of sustainable development as well as undertake operational functions such as supporting the implementation of environmental treaties and related action plans at local, national and regional levels.

In the developing countries, many governments also followed suit, establishing their own versions of national environment agencies. In Latin America, in 1973 Brazil established a Special Secretariat for the Environment later (by 1999) transformed into the Ministry of the Environment. In Africa, Tanzania, with long history of natural resource conservation, established a National Environment Management Council in 1983. In Asia, China established the National Environmental Protection Agency in 1984,6 later upgraded to a State Environmental Agency (SEPA) in 1998, operating at ministerial level, and since 2008, it is the Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China (Wikipedia 2013).

In 1979 the Geneva Convention on Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution that regulated the emissions of noxious gases was adopted and concern with depletion of the ozone layer led to the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, 1985 and its Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone layer.7 The protocol facilitated the gradual withdrawal of the chlorofluoro-carbons (CFCs) that destroy the ozone layer.8 The capstone of this period was the World Commission on Environment and Development (the Brundtland Commission, 1983–1987), which issued the report Our Common Future9 and placed emphasis on sustainable development (defined as: development that ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’).

By the early 1980s, global attention was increasingly focused on the effects of the rising average temperature of the earth’s atmosphere, identified as global warming, and its causes – GHGs, with carbon dioxide (CO2) as a principal agent.10

The pattern of rising carbon dioxide CO2 and the correlative warming links with atmospheric global temperature rise, through the so-called greenhouse effect, had been theorized since the nineteenth century by Jean Fourier (1820) and Svante Arrhenius (1896).11 Anthropogenic (human caused) CO2 as the key driver of global warming through the burning of fossil fuels was identified by Svante Arrhenius and Thomas Chamberlin (1896) and John Tyndall in the mid-to late nineteenth century. By the middle of the twentieth century, scientists such as Roger Revelle, Hans Seuss and Charles Keeling were able to empirically verify the threat of rising levels of overhang of CO2 in the atmosphere.12

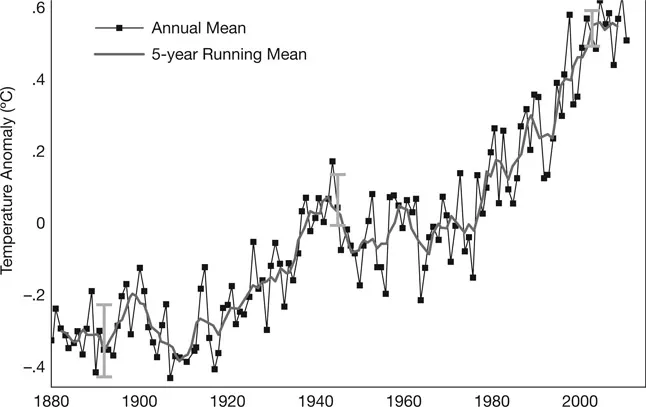

GHGs such as carbon dioxide, water vapour, nitrous oxide, methane, halo carbon and ozone prevent heat from escaping the earth’s atmosphere much the same way as the locked windows of a car traps heat inside the car. This warming effect is raising the average temperature of the earth to current level of 0.8 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial level and could conservatively exceed 4 degrees Celsius by 2100 (Figure 1.1). There are noticeable, significant and growing interactions between carbon dioxide and climate parameters such as rainfall and temperature change as well as the adverse impact on sea level. These intertwined factors and their dire implications for food production, forest and ecosystem services and the availability of clean fresh water led to climate change becoming centre stage in the global environmental discussion.

Rising sea level puts at least 200 million people’s lives at risk. Rising temperature is associated with natural migration of mosquitos and hence increased susceptibility to incidence of both vector borne diseases such as dengue (Eastern Caribbean) and malaria (Uganda and Rwanda),13 and non-vector-borne infectious diseases such as cholera and salmonellosis. Floods and the salinity of water increase toxic intrusion into water catchment areas and pose severe consequences for human and health systems, biodiversity and the continuation of specific animal and plant species. Climate change, hence, is seen as a severe threat to human and ecological survival.

Though rising atmospheric carbon dioxide can occur due to naturally occurring warming processes such as the solar (sun) energy on the earth’s orbital cycle and ocean circulation, empirical evidence show that anthropogenic GHG such as fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gases) burning since the beginning of the industrial revolution (1700s) is the major cause of rising CO2. Naturally generated carbon dioxide trend has not risen significantly and commensurately with the increasing warming of the earth’s atmosphere to be the primary causal factor in global warming.

Figure 1.1 Global land-ocean temperature index

In the early 1980s, both the US National Academy of Science (NAS) and the Environmental Protection Agency issued studies that concluded that anthropogenic sources of CO2 were ...