eBook - ePub

Educating African American Students

And How Are the Children?

Gloria Swindler Boutte

This is a test

Share book

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Educating African American Students

And How Are the Children?

Gloria Swindler Boutte

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Focused on preparing educators to teach African American students, this straightforward and teacher-friendly text features a careful balance of published scholarship, a framework for culturally relevant and critical pedagogy, research-based case studies of model teachers, and tested culturally relevant practical strategies and actionable steps teachers can adopt. Its premise is that teachers who understand Black culture as an asset rather than a liability and utilize teaching techniques that have been shown to work can and do have specific positive impacts on the educational experiences of African American children.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Educating African American Students an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Educating African American Students by Gloria Swindler Boutte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Educación multicultural. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AND HOW ARE THE CHILDREN?

Seeing Strengths and Possibilities

Proposition 1.1 There is a need to illuminate the existing strengths of African American children, families, communities, and schools and to disrupt the prevailing discourse of Black inferiority.

Proposition 1.2 Black culture is an asset and source of strength.

Proposition 1.3 Equity, not equality, is the goal.

In light of the seemingly perpetual and alarming statistics about African American students, educators need to know that our work matters more than we can imagine. Black students will not succeed without us, and we are their lifelines to a better future (Delpit, 2012). Nevertheless, as educators, we can also be complicit in the process of students’ nonsuccess, albeit often unintentionally or because we are unaware of the larger implications and influence of our actions and practices. In order for changes to occur in the pervasive, negative trends faced by Black children, doing nothing is not an option for educators who care about Black children and want to contribute to improving the education process on their (students’) behalf. Acknowledging the inherent strengths, beauty, and humanity of Black students and their communities, each of us must find ways to make a positive and impactful difference and to teach for the liberation of African American students, such that optimistic educational and economic opportunities are not foreclosed for them.

This chapter, then, provides an overview of foundational ideas that will be explained in more detail in subsequent chapters. Although many educators will want to delve into “solutions” and strategies immediately, the intent of this book is to provide a comprehensive conceptualization, instead of a shallow recipe and “quick fix.” Hence, some background on the issues facing African American students is necessary. Because African and African American cultures have a rich and strong storytelling tradition, I seek to honor that tradition by beginning with a story. This story has been passed down over the generations and across cultures, and its guiding question serves as the key theme of the book. It is my hope that this story and its guiding question will direct educators’ attention to the need to prioritize the care of children and, in this case, of African American students.

And How Are the Children?1

Among the most accomplished and fabled groups of warriors were the mighty Masai warriors of eastern Africa. No tribe was considered to have warriors more fearsome or more intelligent than the mighty Masai. It is perhaps surprising, then, to learn that the traditional greeting that passed between Masai warriors was “Kasserian Ingera,” which means, “And how are the children?” Even warriors with no children of their own would give the traditional answer, “All the children are well,” which indicated that, when the priorities of protecting the young and the powerless are in place, peace and safety prevail.

This is still the traditional greeting among the Masai people of Kenya. It acknowledges the high value that the Masai place on their children’s well-being. The Masai society has not forgotten its reason for being, its proper functions and responsibilities. “All the children are well” means that life is good. It means that the daily struggles for existence do not preclude proper caring for their young.

Gleaning insight from the Masai, we may ask how our own consciousness about our children’s welfare might be affected if we took to greeting each other with this daily question: “And how are the children?” I wonder whether, if we heard that question and passed it along to each other a dozen times a day, it would begin to make a difference in the reality of how children are thought of or cared about in our own country. What if every adult among us, parent and nonparent alike, felt an equal responsibility for the daily care and protection of all the children in our community, in our town, in our state, in our country, and in our world?

Imagine what it would be like if heads of government (e.g., presidents, governors, mayors) began every press conference, every public appearance, by asking and answering the question: “And how are the children?” Envision beginning every faculty or school meeting with the same greeting. It would be interesting to hear their answers. I wonder if they could truly say, without any hesitation, “The children are well. Yes, all the children are well.” (And how are the children, 2013).

Indeed, in some settings, the answer to this compelling question may actually be “The children are well.” However, if we asked, “And how are the Black children in America?”, the answer would not likely be a promising one in most schools and would more likely be a resounding, “The children are not well,” in most cases.

Sustained interest in the welfare of Black children is rarely seen outside circles of Black families, communities, and professional groups. Would we, as a country, tolerate the same dismal trends that Black children face for White children?

Early in their lives, many Black children hear (and learn) the message that they are devalued (Perry, Steele, & Hilliard, 2003). For example, I am reminded of the children’s chant:

If you’re white, you’re alright

If you’re brown, stick around

If you’re yellow you’re mellow

But if you’re black, get back.

I have found it difficult to engage a sustained and non-deficit interest in Black children from people outside Black communities—and sometimes, even within the community. Metaphorically, my efforts have been like those of a doctor trying to convince a person to diet or exercise for their own health benefits. In either case, the person has to give up something that he or she likes (unhealthy food) and has to exert more energy. In the long run, however, the benefits outweigh the sacrifices. In the case of transforming schools to meet the needs of Black children, educators will have to relinquish aspects of white privilege or internalized racism in order to retool and transform their teaching. Nevertheless, the end result will be beneficial to them, as teaching African American students will be viewed as rewarding rather than cumbersome, and the children will be well. Indeed, if we are to build a just and equitable world, we must begin with the children, as they are the key to our survival and the barometer of how we are doing as a society.

What Does All of This Mean for Educators?

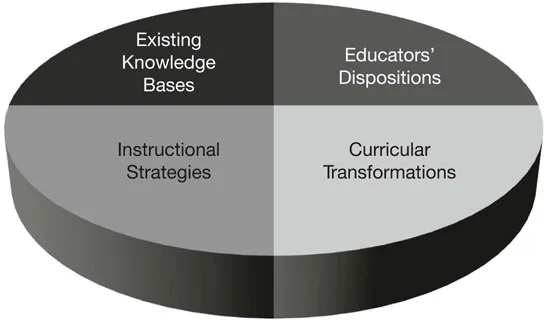

So how does all of this translate to changes in the classroom? What do teachers need to effectively teach African American students? In order for African American students’ negative performance trends to change, educators typically need to make adjustments in their (a) existing knowledge bases, (b) dispositions, (c) instructional strategies, and (d) curriculum. Recommendations for addressing the four components shown in Figure 1.1 will be included in each chapter. A brief description of each component follows.

• Knowledge bases: This book makes much of the substantive existing body of knowledge accessible to teachers and teacher educators. This includes frameworks for thinking about teaching African American students that demonstrate how to engage aspects of Black culture as an asset versus a liability.

• Dispositions: In order to effectively teach African American students, we educators often have to reframe what we think about the students and their homes, as well as how we view ourselves, our social identities, and our roles in this process. Because of endemic racism in schools and society, many educators may have difficulty seeing existing strengths among African Americans. An explanation and accompanying exercises in Chapter 2 will make this point clearer. Additionally, understanding how one’s own cultural perspectives, experiences, and preferences influence teaching and learning is essential.

FIGURE 1.1 Key Areas of Change.

• Instructional strategies: This book explores instructional strategies—some conventional and some nonconventional—that have been shown to be effective. The role of teachers is pivotal, as the relationships that they have with students, families, and communities are important parts of this process. Recommended strategies in this book are elastic enough so that they can be adapted for educators’ respective classrooms and educational spaces.

• Curriculum: This book demonstrates ways to make the curriculum relevant to African American students. An emphasis will be placed on, not only building on what students know, but extending their perspectives, knowledge bases, and worldviews as well. A case is made that, by providing multiple and global perspectives, educators will meet and exceed existing standards. It will be important for educators to recognize and understand that curriculums and standards are not neutral or culture-free. Typically, standards are “culturally relevant” to White, mainstream students, as most of the content is Eurocentric in nature (Banks, 2006; Boutte, 2002b). Hence, it is not surprising that performance trends favor students from mainstream and/or White ethnic groups and disadvantage African American students.

Focusing on what we, as educators, need to change is not intended to romanticize Black students and communities, or to not contend with problematic elements that may exist (Paris & Alim, 2014). Rather, as there has been an overemphasis on what is wrong with Black students and communities and what they need to change, the intent is to focus on what we as educators can change and what strengths already exist that we may build on.

Guidelines for Processing Information and Activities in This Book

It is impossible to discuss educating Black children without talking about race. Acknowledging the provocative and sensitive nature of discussing issues of race and other types of oppression, it is useful to set guidelines. Educators may find the following suggestions to be helpful (Hardiman, Jackson, & Griffin, 2007).

1. Be willing to tolerate some discomfort while reading this book. Keep in mind that discomfort/disequilibrium is a part of the growth and transformation process. It may be helpful to remember that many African American students experience discomfort for most of their school experiences. So, on behalf of the children, I am asking that educators remain open to trying to process and understand the issues presented in this book. If Black children have been experiencing long-term discomfort, surely we, as educators, can tolerate discomfort on their behalf during the short time that it takes to read this book.

2. If you find yourself withdrawing or resisting information, recognize that you may be on a learning edge and poised to learn something new. It is helpful to know that you may experience strong feelings when you are on a learning edge, such as annoyance, anger, anxiety, surprise, confusion, and defensiveness. If you retreat at this point, you may lose an opportunity to expand your understanding. Again, keep in mind your reason for doing this (for the children) and perhaps seek support and guidance from others who are engaged in this process.

3. Be alert to words or phrases that serve as triggers for you. Triggers are instantaneous responses without accompanying conscious thought. If something triggers you, try to reflect on why it is a trigger for you. A few examples of triggers for me are included in Table 1.1, along with accompanying explanations for why they are triggers for me and what I have to do to move past them. After reading them, write down examples of some of your triggers and how you may process them, so that you will not be deterred in your quest to become an excellent teacher of African American students. It is also important to realize that some of your comments may trigger others.

4. Lastly, in terms of guidelines, I urge educators to see issues beyond their own experiences and to see things from the perspective of what schooling is like for far too many African American students. Recognize that, as educators, we cannot do everything, but we can change what is done in our own classrooms. Continuing to do the same things that have been shown to be unsuccessful will lead to the same results. As educators, we have to accept the roles that we play in continuing negative social and academic trends, albeit unintentionally at times. Educators are encouraged to “Believe in the possibility of the Black child” and determine what is possible within our sphere(s) of influence (e.g., classrooms).

TABLE 1.1 xExamples of Triggers for Me

Triggers | Commentary | How I temper my response and move forward |

Black parents don’t care about their children or Blac... |