![]()

Chapter 1

Attachment and assessment

An introduction

Steve Farnfield and Paul Holmes

Introduction

This chapter introduces the theoretical underpinnings of attachment together with some observations on the assessment of attachment in professional contexts. It provides the theoretical background to the review of the most widely used assessments of attachment and parenting, which are the subject of Chapter 2.

One of the most accessible and popular accounts of attachment behaviour can be found in the work of the British naturalist and television presenter David Atten-borough. In his programmes we see how all species, from insects to birds, fish to reptiles, and all the mammals (not just us), have evolved ways of keeping themselves alive long enough to reproduce and then protect their offspring to the point where they can, in their turn, reproduce and pass on their genes.

Animal behaviour, and the evolution of strategies for the survival of the species, was central to the theory of human attachment developed by the British psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby. When he began his career in the 1930s one of the explanations for the bond between mother and child was food. However, studies by Lorenz (1935) had showed that goslings became attached to adults, including humans, who did not feed them, and Harlow (1958) demonstrated that when under stress, infant rhesus monkeys preferred a cloth-covered dummy monkey that offered some comfort rather than the wire version that produced food. Bowlby, using his own observations of delinquent boys, and his study for the World Health Organisation of children traumatised by war (Bowlby 1953) used this knowledge to develop his own theory of attachment: a biologically based behavioural system that functions to protect the child from danger by maintaining the accessibility or proximity of a caregiver, whom he called their ‘secure base’; a concept introduced with his colleague Mary Ainsworth (Ainsworth & Bowlby 1991; Bowlby [1988] 1998: 11).

Attachment is related to a number of other important behavioural systems, namely: play and exploration; affiliation (in children the ability to use adults, such as nursery workers, as secondary attachment figures) and friendships; mate selection and then caregiving (typically as parents).

Compared to other species the attachment process in humans is complex. Our children remain dependent on adult protection for a long time, and, when contrasted with other apes, our superior analytical faculties enable us to reflect on our behaviour and that of the people with whom we live. This reflective capacity is the subject of a considerable body of work by Fonagy and colleagues, called by them ‘mentalisation’, who argue that the evolutionary role of attachment goes beyond the protection of infants (Bowlby’s starting point) and functions to develop the social brain. ‘The major long-term selective advantage conferred by attachment is the opportunity to develop the sophisticated human social intelligence that physical and emotional nearness to concerned adults affords’ (Luyten & Fonagy, Chapter 13).

This ability to process information about the self in relation to the outside world has been given a different conceptual framework by Patricia Crittenden (a student of Ainsworth’s). Unlike Fonagy and colleagues’ emphasis on the link between social intelligence and attachment security, Crittenden’s emphasis is on surviving danger. For Crittenden it is danger, not safety, that has characterised human experience over time and attachment behaviour has developed as a sophisticated means of survival (Crittenden 2006, 2008).

In terms of assessing attachment, the reflective capacity of our species, coupled with language, means that unlike the subjects of Attenborough’s films, we can not only observe attachment behaviour in humans but also ask older children and adults about their mental representations of attachment by interviewing them.

Attachment

Attachment is not just another word to describe important relationships but refers to that particular aspect of behaviour by which we are drawn to particular people for safety and protection when we feel anxious and unsafe. Early on in the relationship with their carers, babies start to learn how to maximise the protection available to them and, in cases where parents do not protect their children adequately, how to minimise the threat to their survival. As Crittenden notes: ‘attachment behaviour is the infants’ contribution to enabling caregivers to protect and comfort them … Patterns of attachment are infants’ strategies for shaping mother’s behaviour’ (Crittenden 2005: 1).

Ainsworth’s observations of young children and their parents led her to suggest that a child’s attachment might be considered to lie on the dimension of security/insecurity (Bowlby [1969] 1971: 401; Ainsworth & Bowlby 1991: 8). These terms have remained central to attachment thinking and research ever since.

Securely attached infants and preschool children do not have to invest huge amounts of emotional time or focused attention on their moment by moment attachment to their ‘secure base’ because their environment is predictably protecting and comforting. They can devote resources to exploration, play and self-discovery. Such children are able to form trusting and emotionally open relationships with their parents and then subsequently with their peers and, in due course, in their adult intimate relationships.

Conversely insecure attachment involves diverting attention to survival and developing behaviours which, while functional when under threat can be less than optimal when conditions are safer. Depending on the degree and type of insecurity, this can bring all manner of personal and relationship problems.

Who is an attachment figure?

Howes and colleagues define an attachment as a person who provides:

1 Provision of physical and emotional care

2 Continuity or consistency in a child’s life

3 Emotional investment in the child.

(Howes et al. 1999: 675)

The central point is that, to be an infant’s attachment figure, the adult must be readily accessible for a significant proportion of that child’s daily life. Thus fathers who live abroad or are in prison cannot be attachment figures, and in a situation where a baby is removed at birth to a foster home and his mother visits him for a few hours a day, the primary attachment figure is likely to be his foster mother and not his birth mother. This must be borne in mind when undertaking any assessment of attachment. As a rule of thumb, for young children we can start by asking where does the child spend the night? The person who provides night care is likely to be the main attachment figure (see Solomon & George 1999b on shared care in separated families). Children, like adults, typically form attachments to more than one person, with one carer being perceived as more protective than the others (Bowlby 1969). In an evolutionary context this has survival value in that the child does not have to waste precious seconds choosing which person to run to when under threat, but he also has available options if this preferred person is unavailable or dead.

Although Bowlby acknowledged that the primary figure does not have to be the mother, attachment research was, for decades, preoccupied with the mother–infant relationship and has yet to develop a comprehensive theory that embraces the total network of care. Across cultures and time children have been brought up by biologically related groups of women. Mother is important, often the primary, but not the sole attachment figure (De Loache & Gottlieb 2000; Weisner & Gallimore 1977).

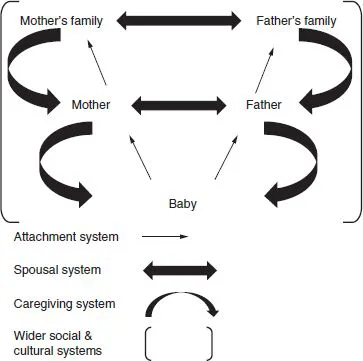

Even when alone with her mother a baby is nested in a number of interlocking systems so she is like the smallest figure in a clutch of Russian dolls (see Figure 1.1). Her mother has an attachment to her parents and wider family (mother’s childhood attachment system) and she also has a relationship with the baby’s father (the spousal system), whose influence is usually relevant even if they live apart, and he has attachment figures and siblings and so on. They might also be involved in a professional system of social workers, lawyers, psychologists and other agencies. They live in a community that is maybe safe or very dangerous. And they live in, or may have emigrated from, a society which has its own history of threat, safety and survival (see Arnold in The Routledge Handbook of Attachment: Implications and Interventions (Holmes & Farnfield 2014b)). It is all these systems that combine to bring the baby up (Farnfield 2008). Parents are the point of service delivery that will determine baby’s future attachment strategy, but they are far from the whole story. A fully developed systemic theory of attachment may one day reflect this (see Dallos, Chapter 12). Although there is an increasing number of cross-cultural studies of attachment, the available assessment tools have been fashioned in the context of Western nuclear families and there is an urgent need to develop ways of assessing children’s attachment security in the context of more complex social networks, as well as cultural variations in one-to-one child care (Van IJzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz 2008; Reebye et al. 1999).

Figure 1.1 Nested Systems

ABC: the first steps in the assessment of attachment

Bowlby was always concerned that his theory needed to be supported by good quality scientific research. Indeed evidence-based practice, and the associated problems of striving for objectivity in assessments, is essential in professional activities which often carry significant implications for the future of their subjects. One of the attractions of the validated assessment procedures which are the subject of this volume is that they have a ‘scientific’ quality which promises to reduce professional prejudice and bias. The downside is that they were designed to validate the underlying concepts of attachment theory (Solomon & George 2008) and so the majority were developed within an academic rather than clinical context and do not always translate very easily to everyday clinical practice.

The Strange Situation

The first steps in the research process were made by Mary Ainsworth who began by observing small children with their families first in Uganda and then in Baltimore, USA, where she developed the Strange Situation procedure (SSP), a laboratory procedure that assesses attachment behaviour in infants following two brief separations from their mothers (Ainsworth et al. 1978). Ainsworth observed three broad categories of response which, following discussions with Bowlby, were labelled A, B and C until they had a better idea about what they meant (Karen 1998). This ABC notation has remained at the centre of all subsequent research into attachment and the behaviours are typically described as the following types:

A insecure-anxious avoidant

B balanced or secure

C insecure-anxious ambivalent/resistant

In the SSP there are also qualitative differences in the infants’ play, illustrating a central construct of attachment theory, i.e. the balance between the attachment system (highly activated when anxious) and the exploratory system (muted when anxious and activated when feeling safe). The SSP has remained the gold standard of attachment assessment and is discussed in more detail by Teti and Kim in Chapter 4.

It is important to note that all assessment procedures are a snapshot in time and that it is not the person but their behavioural strategy that is being assessed; i.e. an individual is not ‘a Type A, B or C’ but deployed during the assessment a Type A, B or C attachment strategy. Hence, we prefer the description of their being in Type A, B or C rather than s/he is a Type A, B or C. We also prefer the terms ‘attachment strategy’ or ‘pattern’ in order to emphasise the developmental and interpersonal characteristics of attachment behaviour rather than ‘attachment style’ which suggests a personal trait (see Buchheim & George 2011).

What the SSP assesses is the infant’s expectations, based on previous experience, regarding his mother’s response when he shows her that he feels distressed. Bowlby described these expectations in terms of an ‘internal working model’ of attachment, a term subsequently revised by Crittenden to ‘dispositional representations’ of attachment relationships (Crittenden 2008; Crittenden & Landini 2011). Crittenden’s revision was designed to tie her use of information processing and memory systems to current neuroscience (see below).

These mental representations of self and others develop in infancy in interaction with caregivers, and provide a blueprint for all other relationships (Bowlby [1973] 1980) both reflecting past experience with carers and contributing to the shaping of relationships in the present (Bretherton 2005; Bretherton & Mulholland 2008). Children in Type A have learned that their distress is likely to be consistently ignored or rejected, and so they develop attachment strategies based on minimising demands on their carers and attempting to look after their own needs. Children in Type B have learned that their needs will be attended to and they will be comforted. Those in Type C have no clear idea what their parent will do but discover that by raising their arousal (for example, by crying or screaming) that their parent will respond eventually to their signals.

Bowlby described the development of attachment in terms of four phases, and by about the fourth year a ‘goal-corrected partnership’ becomes evident in that children have a relatively sophisticated theory of how other people’s minds work (Marvin & Britner 2008). This means that rather than immediate physical proximity to attachment figures, children can make use of internal representational models of the availability of carers. For example, they can wait for mother to finish something before attending to them or they can call her up on the pretend telephone in the home corner when at nursery.

The early work with the Ainsworth classificatory system threw up difficulties in assigning...