eBook - ePub

Night Photography and Light Painting

Finding Your Way in the Dark

Lance Keimig

This is a test

Share book

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Night Photography and Light Painting

Finding Your Way in the Dark

Lance Keimig

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Lance Keimig, one of the premier experts on night photography, has put together a comprehensive reference that will show you ways to capture images you never thought possible. This new edition of Night Photography presents the practical techniques of shooting at night alongside theory and history, illustrated with clear, concise examples, and charts and stunning images. From urban night photography to photographing the landscape by starlight or moonlight, from painting your subject with light to creating a subject with light, this book provides a complete guide to digital night photography and light painting.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Night Photography and Light Painting an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Night Photography and Light Painting by Lance Keimig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médias et arts de la scène & Médias numériques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

GETTING STARTED

1

THE HISTORY OF LIGHT PAINTING

FROM FLASH POWDER TO FLASHLIGHTS

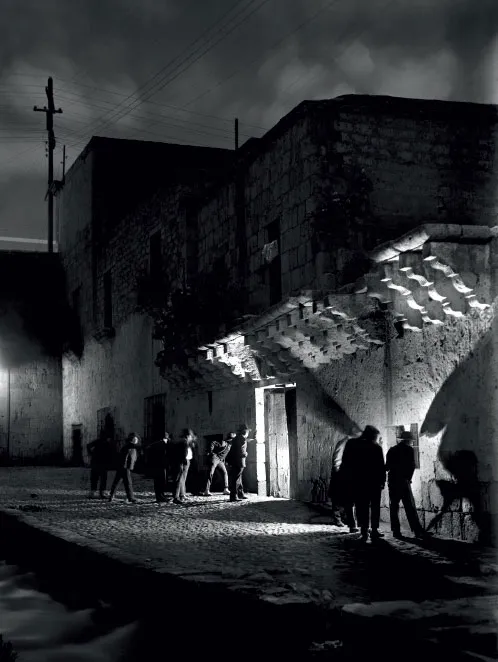

“Nocturne: Aqueduct of Izcuchaca,” Arequipa, Peru, Carlos and Miguel Vargas, ca. 1920

Underappreciated pioneers of night photography and light painting, the Vargas brothers were probably the first to apply light painting techniques for artistic purposes. It is just possible to make out a faint image of one of their assistants holding a bottle filled with flash powder. Their Nocturnes were clever, beautiful, and technical masterpieces of the time.

In the first edition of this book, I wrote about the history of night photography, a subject that has fascinated me for a quarter of a century. Rather than simply reprint that chapter here (available for free as a PDF on my website: thenightskye.com/FYWITD_ch1.pdf), the following pages introduce the history of light painting. Like night photography, light painting and drawing have become increasingly popular in recent years. It has been used frequently in advertising in print and on television, and there are a variety of highly specialized light painting tools that have been developed by light painters, and even a few that are sold commercially.

This book conforms to the common usage of the general term “light painting,” which refers to lighting added by a photographer and combined with a long exposure to make an image, either at night or in a darkened interior. Light painting includes both using added light to illuminate a scene, and any lights pointed back toward the camera to create patterns of light. The term “painting with light” is defined as the use of a handheld light source that is usually moved during the exposure to light part or all of the scene in a photograph, and the term “drawing with light” is used when a handheld light is pointed back toward the camera to create shapes, text, or abstract designs. In painting with light, the added light illuminates the subject. In drawing with light, the light added by the photographer actually is the subject. Light painting includes both painting with light and drawing with light. The more traditional placement of stationary lights that are used to light all or part of the scene is referred to simply as location lighting. It is somewhat awkward and unfortunate wordage, but we need to distinguish between the different types of lighting, and this is the common terminology. Hopefully, it will all make sense once you start reading through the chapters.

This chapter might be more accurately called A History of Photography with Added Light, as it follows the development of location lighting, and eventually drawing with light and painting with light, concurrently with the development of night photography from the early years of the medium up until about 1990. Tracing the origins of light painting as an art form is fraught with dead ends and pitfalls because there is scant photographic or written documentation of early experiments. The genre had never been clearly defined or even established as a medium until very recently. The coalescence of a light painting “community” brought together by the internet and photo sharing sites like Flickr and 500px is a welcome and very recent development. It is impossible to say who was the first, or who first intended, to illuminate a photograph by painting or drawing with light. Most 19th-century photographers who used artificial light in their images did so out of necessity, rather than for artistic purposes. The early photographic materials were not very light sensitive, and were difficult to use. Before the introduction of the dry plate negative in the 1870s, simply managing to make images in the dark was a major accomplishment.

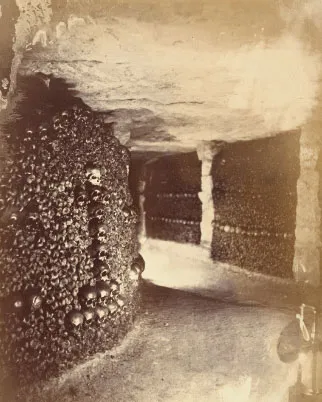

“View in the Catacombs,” Paris, Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon], 1861

Nadar is credited with a number of firsts, including the first aerial photographs, which he took from a hot air balloon. In the early 1860s, he photographed the sewer tunnels, and the catacombs that were discovered underneath Paris during the construction of the Metro. In the lower right-hand corner of this image, a crude magnesium lamp is visible. He used these lamps to light the passageways of the catacombs.

The French photographer Nadar was one of the first to add artificial light to a scene in order to photograph it. Nadar photographed the catacombs and sewers below Paris, making about one hundred wet-plate glass negatives between 1861 and 1862. He used both lamps that burned strips of magnesium wire and electric lights powered by primitive batteries for these photographs, and employed mannequins to represent workers, because of the lengthy exposures.1 The wet-plate collodion process that Nadar used was a significant technical advance over the earlier Daguerreotype, but these plates had to be exposed and developed before the emulsion dried. The lengthy exposures required underground made wet-plate photography impossible without added artificial light.

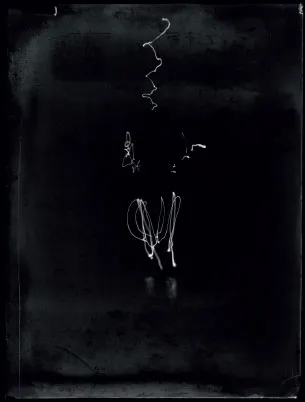

Étienne-Jules Marey and Georges Demeny were French physiologists working together in the 1880s to study and understand movement and locomotion. They were contemporaries of Edward Muybridge, and concurrently developed an alternative method of recording movement that recorded multiple images on a single film as opposed to Muybridge’s method, where each image was recorded on a separate frame. Marey and Demeny’s invention was a precursor to the motion picture camera, and Marey would later work with the Lumière brothers during the development of their camera.2 This work was not directly related to light painting per se, and they were using photography for scientific rather than artistic purposes. However, in 1888–1889, Demeny used a technique known as the Quénu method to record patterns of both involuntary movements such as tremors, and also to understand the physiology of locomotion. The Quénu technique involved attaching incandescent light bulbs to the joints of a subject in order to more easily observe movements.3 Demeny advanced the technique by making long exposure photographs, resulting in what are now presumed to be the first light drawing photographs.4

Edward Steichen made a significant contribution to the genre of night photography and light painting with his series of 1908 photographs of the French sculptor Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac. These images were made primarily by the light of the Moon at Rodin’s suggestion.5 Although there had been various other efforts to photograph by moonlight before Steichen, most notably by John Frith of Bermuda, who made moonlit exposures of up to six hours in 1887,6 it is the Balzac photographs that are the best extant examples of early moonlight photographs. Because there was no precedent for determining exposures, Steichen made a series of exposures ranging between 15 minutes and an hour over two nights by moonlight, dusk, dawn, and even one by flash.7 This may be the first incidence of long exposure combined with added light, which would become the basis for all light painting in the future.

“Pathological Walk in Front,” Georges Demeny and Étienne Jules Marey, 1889

This image is considered the first light painting photograph. Demeny and Marey were physiologists studying human locomotion, and they created this image by attaching small lights to the joints of a figure who walked toward the camera during a long exposure in a darkened room. Many early light painting photographs were made for scientific rather than artistic purposes.

Frank Gilbreth began his career as a bricklayer, but was frustrated by the inefficiencies in the way that masons performed their work. He believed that there was “one best way”8 to do every task, and devised a system of motion study using photography that he called stereo chronocyclegraph (time-motion-writing). He and his wife further developed the techniques of Marey and Demeny, attaching blinking lights to workers’ arms and legs to record and study their movements in photographs. Like the French physiologists, the Gilbreths had no artistic ambitions; photography for them was a tool to aid them with their work. Where Marey and Demeny’s objective was to study and understand movement, the Gilbreths’ objective was to find the most comfortable and efficient way to perform a worker’s task, increasing productivity for the company and comfort for the worker.

“Efficiency Study,” Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, 1918

Like Demeny and Marey, Gilbreth made light painting exposures for scientific research rather than for art. The Gilbreths worked to improve working conditions by improving efficiency in the workplace.

Carlos and Miguel Vargas Zaconet were two brothers who operated a commercial photography studio in Arequipa, Peru from 1912 to 1927. They were among the first to combine long moonlight exposures. What distinguishes the Vargas brother’s work from Steichen’s Balzac images is that the brothers carefully staged a series of nighttime images with multiple light sources, refining their techniques over a period of years. They placed lights in various locations, both within the scene they were photographing, and outside the frame. They thoughtfully illuminated key elements of the scene, and used moonlight to expose the background over the course of long exposures. They balanced their own added light with the existing light, be it moonlight or streetlights. Photographers before this time had used added light without much regard for aesthetics, but the Nocturnes of the Vargas brothers were carefully designed for maximum visual impact. Indeed, they orchestrated complex scenes with numerous posed figures who often had to hold a pose for extended periods of time. Their creation of their imagery was intentionally choreographed in collaboration with each other and their subjects. The photo historian Peter Yenne surmises that it was advances in photographic technology and the advent of electric light that initially led to this body of work. In an article accompanying an exhibit of the brothers’ work entitled The Vargas Brothers, Pictorialism, and the Nocturnes, Yenne writes that, “Taking a cue from the silent screen, they concocted a series of elaborate tableaux using moonlight, lanterns, bonfires, flash powder and street lamps. These theatrical scenes required exposures of up to an hour, and meticulous attention to detail.”9

Although the Vargas brothers’ photographs are not widely known outside of Peru, their night photographs were more sophisticated than anything that anyone else would do for decades to come. It is unlikely that their photographs were seen by their contemporaries in the US or Europe, lest others would no doubt have copied their efforts. As it was, there doesn’t seem to be a comparable body of work until the late 1950s in the iconic railroad imagery of O. Winston Link and his colleagues. In between the Vargas brothers’ Peruvian Nocturnes, and Link’s railroad images, there were plenty of other photographers photographing at night and experimenting with using light in new ways.

The Hungarian photographer Brassaï produced some of the best-known night photographs of Paris in the 1930s,10 but in terms of lighting, he mainly used the contemporary equivalent of an on-camera flash—a narrow tray of magnesium flash powder held overhead alongside the camera. It was Brassaï’s use of explosive flash powder that led Picasso to give him the nickname of “The Terrorist.”11 The great surrealist photographer Man Ray, who was also living in Paris in the 1930s, made what may have been the first photographs using the technique of drawing with light for artistic expression. Ray’s 1935 series of images entitled Space Writing were thought to be scribbles of light until photographer Ellen Carey discovered Ray’s signature written with light camouflaged in one of the images after a conversation with a curator from the Smithsonian about Carey’s own drawing with light work.12

Bill Brandt, an English photographer who apprenticed with Man Ray in Paris in 1930, was one of many photographers influenced and inspired by Brassaï’s seminal book, Paris de Nuit. He also created several bodies of nighttime images during the 1930s and 1940s, including those published in his book entitled A Night in London,13 and photographs of a darkened London taken by moonlight during the German Blitz in 1939 and 1940.14

“Nocturne: Entrance to the Cabezona,” Carlos and Miguel Vargas, 1920

According to historian Petter Yenne, there’s reason to think that the picture of the men outside a tavern entrance is part of a series commemorating a political uprising protesting the dominance of the central government over the southern provinces. The Cabezona still stands—it was a rambling apartment complex owned by a ...