![]()

Part One

Ngarrindjeri A Distinctive Weave

A “sister basket” made of sedge by Ethel Watson, 1939 (M. Kluvanek)

Collector: N. B. Tindale A15951

South Australian Museum Anthropology Archives

![]()

1

Weaving the World of Ngarrindjeri

Weaving Women

When we weave with the rushes, the memories of our loved ones are there, moulded into each stitch. And, when we’re weaving, we tell stories. It’s not just weaving, but the stories we tell when we’re doing it. Daisy Rankine explains. Wukkin mi:mini1 means the women’s business of weaving and all the cultural and sacred life which has been part of the Ngarrindjeri people’s ancestry. Ngarrindjeri women are known as weavers of mats and baskets of enduring value and high distinction. They know where the best rushes grow, when, and how to cull and work them. They extol the fineness of the fresh-water rushes; and admire the bundles that other women have prepared. Ellen Trevorrow, the eldest daughter of Daisy Rankine, is rarely seen without a piece of weaving in her hands or close by. When I pick rushes I reminisce and I recall Nanna, yes, Nanna Brown. I lived with her at Marrunggung [Brinkley] and I was named after her. She was a hard worker. Ellen asks that the first time I mention her, I give her full name, Ellen Brown Rankine Trevorrow Wilson, so that her heritage will be known. One does not call names lightly.

Ellen Brown, after whom Ellen Trevorrow is named, was the daughter of Margaret “Pinkie” Mack, a major source of information for researchers in Ngarrindjeri lands. Pinkie Mack’s mother, Louisa Karpany, could recall when the first white explorers came into her lands. The stories told in this family reach back to first contact, and the family speak with enormous respect of their “Old People”. It is “Queen” Louisa, and Daisy Rankine always identifies Pinkie Mack as “the last initiated Ngarrindjeri child”. When Daisy Rankine speaks of the creation of Ngarrindjeri lands she invokes Pinkie Mack: Nanna told stories of the waters and the mulyewongk [bunyip] underneath; of the pelicans and the sea turtle come into the deep reaches; and of the pondi [Murray cod] come down this way. From Queen Louisa, down through Pinkie Mack, to Ellen Brown (and her sister Laura Kartinyeri who was not as interested in weaving), to Daisy Rankine, and Ellen Trevorrow, this is a distinguished line of weavers and story-tellers. The next two generations are growing up in a world rich in history, oral and written.

Louisa Karpany 1821–1921

Margaret (Pinkie) Mack 1858–1954

Ellen Brown 1905–1979

Laura Kartinyeri 1906–1995

There is a whole ritual in weaving, says Ellen, and for me, it’s a meditation. At Camp Coorong I watch as Ellen patiently encourages a child to begin the circle, to take the lace and to tighten each knot. Deft fingers work the bundles of rushes. The form of the piece emerges. From where we actually start, the centre part of a piece, you’re creating loops to weave into, then you move into the circle. You keep going round and round creating the loops and once the children do those stages they’re talking, actually having a conversation, just like our Old People. It’s sharing time. And that’s where a lot of stories were told. Ellen’s quiet, confident manner holds the children as they struggle to form the centre by twisting the first knotted bundle back on itself. Then they get into the rhythm of the looping through, tightening, and adding new rushes. There is a busy buzz in the classroom. The technique is deceptively simple, and initially it is the sociality of the activity that draws me in to the weaving and from there to the stories of the weavers. Women smile as they recall memories of a favourite aunt or grandmother weaving late into the night and admit that, when they weave till the wee small hours, their children and husbands understand their tired state at breakfast. There is indeed a ritual, a rhyme and a rhythm to weaving.

As a weaver I have to pick and dry the rushes, and when I go out for rushes, Ellen explains, I go with my children and my sister’s children and friends. Through this sharing, teaching and learning, when they get to an age, they’ll know. They’re learning about the land, about the best places for rushes and how to pick them, about the different species, kukundo and pinkie, from the southeast, and marnggato from the Coorong.2 To talk about weaving is to talk about family and country in an intimate way. All my children are weavers, Ellen announces with pride, And now, Corina, my granny [grandchild], she’s five, said to me the other day, “Nanna, it’s my turn now.”

Stories and memories of loved ones sustain and structure the Ngarrindjeri social world; explain the mysterious; provide a secure haven in an otherwise hostile world; bring order to and confer significance on relationships amongst the living; hold hope for future generations; and open up communication with those who have passed on. The stories of cultural life recall the creation of the land, of the seas, rivers, lakes and lagoons. They tell of the coming into being of fish and fowl, of the birds of the air and beasts of the fields. They spell out the proper uses of flora and fauna. These are stories of human frailty and triumph, of deception and duty, of rights, responsibilities and obligations, of magical beings, creative heroes and destructive forces. Everything has a story, but not everyone knows every story. Nor does everyone have the right to hear every story, or, having heard it, to repeat the words.

“Get Aunty Maggie to tell you that ghost story,” I’m told when I ask about muldarpi, the travelling spirits of the sorcerers, strangers, and clever people, who visit after dark, and whose appearances and behaviours are carefully analysed by those present.3 “Ask Aunty Veronica,” I’m told when I inquire about the Seven Sisters Dreaming and the transmission of women’s restricted knowledge about that story. I learn that sisters Val and Muriel will tell me about the mysterious water monster, the mulyewongk at Marrunggung; and I already know that Dr Doreen Kartinyeri is an expert on family history, and much more. And so it goes. This one knows about being taken away and raised in an institution, that one of growing up on the mission at Raukkan (Point McLeay) or at Point Pearce (Yorke Peninsula), another of surviving in the fringe camps of the towns along the Murray River.

Daisy Rankine 1936–2009

Ellen Trevorrow 1955–

Tanya 1978–

Ellen 1996–

Almost everyone to whom I speak knows about the mingka bird, the harbinger of death, but people differ regarding the call and how to read its significance. Ron Bonney of Kingston and Mrs Jean Gollan of Point McLeay name Mount Barker as a mingka bird site (Hemming 1987: 8), but Eileen McHughes is the only person I hear from who has seen the bird. Her story of the encounter weaves family and familiar places. I remember her telling us, says her younger sister Vicki Hartman, after Eileen has finished telling her story to an enthralled audience. Most everyone knows that the ritjaruki, the Willie wagtail, is the messenger bird, but once again there are different interpretations of its behaviour. Doreen watches the one in my garden at Clayton to be sure everything is all right. Is he always there? she asks me. I’ve seen it before, although it is the Murray magpies and the galahs who mass overhead and fill the trees who wake us in the morning. Doreen pursues the question. What was he doing? “Just flying between the house and the fence,” I tell her. “I saw a pair.” She watches for a while and relaxes. He’s happy.

Isobelle Norvill is concerned that variations in detail, pronunciation and interpretation of certain words may be misunderstood. She explained to Judge Mathews: You can go round this area and you talk to different people, and you might hear different words and pronunciations that make it appear that the women you’re talking to are wrong, but nobody’s wrong. You might get a name different to Kumarangk for Hindmarsh Island; it’s still not wrong; it’s still the same, the very same place. The same principles stay and changes happen by conditions. I think that’s very important because it could confuse you a little bit and I don’t want anybody hurt by any statement made like that. Ngarrindjeri “cultural and sacred life”, as Daisy Rankine called it, is a weave of many voices, personalities, histories, remembrances, perspectives, beliefs and practices. At the centre there are “principles”, as Isobelle called them and these can be specified.

The “ownership” of stories is respected by the Ngarrindjeri with whom I speak. “That ghost story” remains Maggie Jacobs’ story. There are many others I am to hear from Aunty Maggie and other women, especially late at night, when we are comfortably settled and all is still. In March 1996, I was present when one muldarpi story was told for the first time. Henceforth, I was able to partake in the retelling and note how the significance of the events is determined. Different people emphasise different aspects of stories and, at each telling, the story is made relevant for the listening audience. It changes “by conditions” as Isobelle said. Stories belong to different places. The mulyewongk at Marrunggung is but one of a number of the creatures who live in the treacherous waters of the Lower Murray River and lakes. Called “bunyips” by early settlers of southern Australia, these large menacing beings made for fascinating children’s and bush yarns, but Ngarrindjeri know theirs is much more terrifying than these whitefella representations and their story has several layers of meanings.

Knowledge is attributed to the elders of this generation and the “Old People” who have now passed on, but it takes more than age to be considered an elder. Elders must be wise in the ways of the land and bestow their knowledge on members of their families who are worthy of such wealth. When Leila Rankine was dying, she deemed her younger sister, Veronica Brodie, to be ready to hear the story of the Seven Sisters constellation. But what Veronica Brodie was told of the Pleiades remains Leila’s story. The relationships in which knowledge is embedded are honoured, and the elder from whom the knowledge came is owed respect. The use of the term “Aunty” for women older than oneself captures something of this notion of respect. Often people were reluctant to name the particular elder, especially if they had passed away. One lesson which has been learned over the past few years is that sacred knowledge may be mocked in the media and the courts, and this is disrespectful to the elders. I also think that for Ngarrindjeri themselves, there has been no need to nominate a particular elder as a source. The “Old People” is a sufficient source and taboos on calling the names of the dead, now somewhat relaxed, would have meant that a personal name would not have been available anyway.4 A kin reference would have sufficed for those present when stories were being told in family groups.

Here and in the following chapters, through the stories of knowledgeable, reflective Ngarrindjeri women and men, I invite you to become familiar with individuals who, story by story, act by act, strand by strand, are actively engaged in weaving their world. Each has a distinctive story to tell. They track back to the knowledge of their forebears and, where possible, I provide a counterpoint from the written sources. At times one echoes the other, but there are also important differences to be noted and explored. The stories celebrate Ngarrindjeri struggles to protect their heritage and are grounded in the current battle over the bridge and earlier intrusions into their land. Through their stories, some handed down from previous generations, others more contemporary, the texture, shape and scope of Ngarrindjeri knowledge, beliefs and practices are made manifest. The stories are for their children and grannies so that they may read of their lives, lore, beliefs, and commitment to the future, and for those who wish to learn more of Ngarrindjeri wurruwarrin, of how these Ngarrindjeri know and believe in their past, present, and future.

Sustaining Stories

I’m Doreen Kartinyeri, a Ngarrindjeri elder. I’ve been interested in recording kinship, Aboriginal history and traditions since working with Professor Fay Gale and the South Australian Museum. I have been able to publish books of genealogies on the Raukkan and Point Pearce families. The first one was The Rigney Family Genealogy in 1983. But my main interest since 1994 has been Kumarangk, Hindmarsh Island. Before the white settlement our families’ ancestors lived there and we do have ancestors buried there. I will do everything I can to protect our sacred sites, heritage, culture, tradition and our grandmothers’ lore. Doreen Kartinyeri has done extensive research into Ngarrindjeri families and what she knows is an important resource in a community for whom kinship is a major topic of conversation and contention. Doreen’s memory for names and dates is something anyone would envy. With her quick mind, inquisitive nature, and respect for knowledge, it is little wonder that her elders invested in her.

Doreen Kartinyeri has been called a “fabricator” by Commissioner Stevens (1995: 287-99), and “theatrical” by Chris Kenny (1996: 136). Philip Jones (1995: 174), of the South Australian Museum, described her as delivering a “standard haranguing” and detailed her treatment of co-workers (ibid.: 4247).5 Before Hindmarsh Island became a household name in Australia, Doreen Kartinyeri’s work was well known to researchers in the Aboriginal field. I first met Doreen in 1981 at a conference with Aboriginal women from all over Australia that I’d helped to organise in Adelaide (Gale 1983). There Doreen Kartinyeri (1983a: 136-57) spoke of her pioneering work on family history at the South Australian Museum; of her long-standing interest in tracing her ancestors and those of other related families; of her concern not to pry and offend; of how she ensures confidentiality; and of exercising discretion (ibid.: 140, 143, 145). Doreen Kartinyeri relies heavily on memory, but she also utilises archives, and the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages. “It was always very important to me to find out what was right. I used to make it my business to find out the truth,” she said at that conference (ibid.: 140). This was her position in 1981. She stated it again in the book of Rigney genealogies (Kartinyeri 1983b: xvii) and it remained her position in 1996. Working with her throughout that year, I had ample opportunity to listen, question, check and double-check. Her accounts of events at which she was present were consistent, and her accounts of relationships with her elders were confirmed by others who were close to her family. When Doreen was not present, or had heard something from someone else, she always said so. She would correct me if I erred. Once when I said she had told me about the animosity between Albert Karloan, who worked with researcher Ronald Berndt, and Clarence Long (Milerum), who worked with Norman Tindale, she said, No. My father told me.

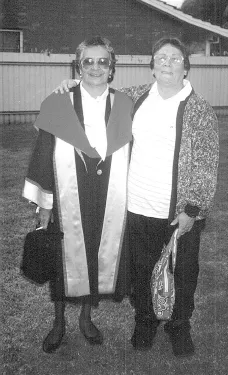

An honorary doctorate: Doreen Kartinyeri with her cousin Edith Rigney, University of South Australia, Adelaide, 1995 (Doreen Kartinyeri’s personal collection)

The shared memories of Ngarrindjeri such as Doreen Kartinyeri, Maggie Jacobs (née Rankine), Daisy Rankine (née Brown), Veronica Brodie (née Wilson), first cousins Eileen McHughes (née Kropinyeri) and Isobelle Norvill (née Wilson), the sisters Val Power (née Karpany) and Muriel Van Der Byl (née Karpany), Sarah Milera (née Day), Mona Jean (née Gollan), Henry Rankine, Neville Gollan, George and Tom Trevorrow reach back across the generation of their parents into the nineteenth century, to the first contacts with white explorers, whalers, sealers, settlers, welfare officers, missionaries and to the visits of various anthropologists. Clarence Long (Milerum) from the Coorong, on whom Norman Tindale relied so heavily for information and knowledge, was a neighbour of Maggie Jacobs at Raukkan, and Granny Ethel Watson (1887–1964), a noted weaver, from Kingston, known locally as “Queen Ethel” was Tindale’s nursemaid. Daisy Rankine remembers the Berndts interviewing her grandmother at Brinkley in the 1940s, and Doreen Kartinyeri has had exchanges regarding her research with both Ronald and Catherine Berndt and with Norman Tindale. The Ngarrindjeri I have met may not always know what has been written about them, but they remember who was visited and asked questions, and they have opinions about the quality of the interactions.

Val Power at Marrunggung (News 19 November 1974)

We didn’t have bookshelves, so we put stories onto the land, says Muriel Van Der Byl. The Karpany sisters, Val Power AM (born 1936) and Muriel Van Der Byl (born 1943), moved from Wellington when their father died in 1944. They lived briefly at Raukkan, while their mother cared for her dying father, and then relocated to Berri where their father’s brothers were settled. They travelled back and forth to Tailem Bend, spent time with their father’s sister, Aunty Janet, visited Goolwa and lear...