eBook - ePub

Chaucer at Work

The Making of The Canterbury Tales

Peter Brown

This is a test

Share book

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chaucer at Work

The Making of The Canterbury Tales

Peter Brown

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Chaucer at Work is a new kind of introduction to the Canterbury Tales. It avoids excessive amounts of background information and involves the reader in the discovery of how Chaucer composed his famous work. It presents a series of sources and contexts to be considered in conjunction with key passages from Chaucer's poems. It includes sets of questions to encourage the reader to examine the text in detail and to build on his or her observations. This well-informed and practical guide will prove invaluable reading to those studying medieval literature at undergraduate level and English literature at A level.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Chaucer at Work an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Chaucer at Work by Peter Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The General Prologue

This chapter, like the ones which follow, is organised around a series of exercises in analysis and comparison. In each case the onus is put on you to assess each passage or picture in turn, on its own merits, as well as to consider it in relation to other material. The point of this type of exercise should now be clear but it is worth reiterating. First, it will introduce you to a particular source or context important for a fuller understanding of Chaucer’s tale. And second, you will be enabled by means of comparison to interrogate Chaucer’s poetry in order to discover something of Chaucer’s working methods, what meaning he was trying to express, and why. The exercises are linked in two ways: by introductory material that provides relevant information; and by a line of argument which builds on your responses. That argument does, of course, betray the intentions and values of the present author but, it is to be hoped, not in a way that predetermines the outcome of your own thinking. The intention is to maintain a dialogue, an interactive relation, between author and reader as far as is possible within the confines of a book. If the end result is a questioning of my own points of view, so much the better.

i. THE PILGRIMAGE CONTROVERSY

Pilgrimage was a controversial topic when Chaucer wrote the Canterbury Tales. It had become a subject of heated debate between the orthodox and reforming wings of the church. In order to understand the terms of those different positions, and their relevance to the General Prologue, it is necessary first to understand what pilgrimage meant in later fourteenth-century England. As we might expect, the Bible provides the basis for the medieval idea of pilgrimage. Adam and Eve, expelled from paradise, were the first exiles who wandered through the world because of their own sinfulness. The Israelites, led by Moses and Aaron, journeyed in search of the promised land. Most influential of all was the homeless travelling back and forth of Christ, a condition imitated in the deliberate homelessness of the early Christian ascetics. The church fathers were acutely aware of the importance of pilgrimage both as a devotional practice and as a metaphor for the human condition. St Ambrose described the Christian life as a three-stage pilgrimage which involves man’s perception of the world as a desert, his determination to wander in search of redemption, and his final acceptance into paradise by Christ. St Augustine viewed human life as a journey either towards the sinful, man-made city of Babylon, or towards Jerusalem, the city of God.

What pilgrimage figures is alienation: alienation from God, caused in the first instance by Lucifer’s act of rebellion, then by Adam and Eve’s, and individually through sin, especially that of pride. Pilgrimage, whether understood literally or figuratively, was a means of signifying and enacting the individual’s desire to return to the lost heavenly paradise. That desire springs from a sense of homelessness and strangeness in this world, a sense that one’s true home is elsewhere, at the end of the ‘journey’. Pilgrimage is therefore an expression of a double alienation: from God and the world. Ideally it is a search for a lost order and integrity.

What, in practice, did pilgrimage entail? At one extreme, it might mean withdrawal from the world to the rigours of a hermetic or monastic life. Here, the idea of pilgrimage is turned wholly inwards to signify the journey of the human soul towards salvation. At the other extreme it could involve an actual journey (the outer performance of the inner need) to sacred places. Those places were usually identified by their association with the life and suffering of Christ or of the saints and martyrs. At the pilgrim’s destination, he or she would find tangible evidence of its sanctity in the form of relics – material remains such as the bones, skin or clothes of the saint, or of associated buildings and objects. Since churches were founded on the basis of the relics they possessed, pilgrimage in practice usually had as its objective a church, within which there would be a shrine housing a relic or relics. The shrine could be quite small and portable, in the form of a reliquary; or it might be large, like the shrine at Canterbury cathedral which contained the bones of St Thomas, martyred in 1170. At the shrine the pilgrim would make an offering and pray, in the hope and expectation that the spiritual supercharge of the place would ensure the efficacy of the prayer. Prayers might also be directed towards healing purposes, the healing of physical ailments being one of the prerogatives of Christ and his canonised disciples. So a pilgrimage was, in theory, an extremely pious act, designed to display devotion and perhaps to secure healing. It could also be an act of penitence, publicly or privately enjoined on an individual to make amends for sin. In order to show his remorse for the death of Thomas Becket, Henry II made a pilgrimage to Canterbury cathedral in 1174. At Harbledown (a mile from the city) he dismounted from his horse and in humble clothes began to walk, pausing half-way to remove his shoes. On reaching the tomb of St Thomas he prostrated himself and was flagellated by the monks.

The modernised excerpt below conveniently sets out in straightforward terms the ideology of pilgrimage. It dates from about 1400, the year of Chaucer’s death, and is from an anonymous treatise, A Mirror to Ignorant Men and Women, of the sort that was to be produced in increasing variety and quantity to cater for the growing numbers of literate lay persons with a taste for private piety and for instruction in the essential components of the Christian faith. Deriving from a French Dominican work of the thirteenth century, it contains a series of expositions on such topics as the Creed, and the vices and virtues, linked by a commentary on the Pater Noster. The roots of the book are in long established traditions of spiritual guidance which urged a close consideration of both the literal and metaphoric implications of the Bible, buttressed with appropriate allusions to the church fathers. The Mirror opens as follows:

It is true that all people in this world are in exile and live in wilderness outside their true country; everyone is a pilgrim or traveller in a foreign country where he may in no way live, but must every hour and minute of the day be passing on his way, as the Bible says: ‘For here have we no continuing city, but we seek one to come’ [Hebrews 13:14]. And the place to come is one of two cities, of which one may be called the city of Jerusalem, that is the city of peace, and the other the city of Babylon, or confusion. By the city of Jerusalem, or peace, should be understood the endless bliss of heaven, where there is endless peace, joy and rest without interruption. And by the city of Babylon, or confusion, you should understand the endless pain of hell, where all kinds of confusion, shame and destruction, sorrow and misery, shall be without end.

And since all of man’s life in this world is like a movement or journey or path to one of these two cities, that is to say to endless bliss or endless pain, the holy doctor saint Augustine in his meditations teaches us and says: with awareness, taking careful thought, superior effort and continual care, we are required to learn and find out by what means and by what way we may shun the pain of hell and obtain the bliss of heaven. For that pain, Augustine says, may not be shunned nor that joy bought unless the way is known. And as we can see that these two cities are opposites, so are the ways that lead to them contrary to each other – which ways be none other but that the one leading to endless bliss is virtues and virtuous living, and the other leading to endless pain is sin and sinful living.

(A Myrour to Lewde Men and Wymmen, ed. Nelson, p. 71)

Now answer the following questions.

1. How does the author of the Mirror express the idea of alienation?

2. What is the nature of reality as expressed in this passage?

3. What is the significance of pilgrimage in the author’s scheme of things?

4. What are the respective attributes of Jerusalem and Babylon?

The writer begins by stating that the basis of the human condition is exile and alienation. Like it or not, we are pilgrims, foreigners, strangers, and our true home is elsewhere. And not only our home, but also reality: the underlying assumption is that the world in which we find ourselves is, in spite of appearances, insubstantial, illusory and fleeting, and that truth and stability are elsewhere. For this view the Bible provides unimpeachable authority, as in the quotation from Hebrews. Having rehearsed, or established, a bifocal perspective on human experience, the unknown author goes on to use duality, binary opposition, as a way both of structuring the argument and of developing its content. Thus a distinction is drawn between Jerusalem – associated with the desirable peace, bliss, heaven, joy, rest – and Babylon – associated with pain, hell, confusion, shame, destruction, sorrow and misery. These then are alternative destinations of the human soul, which may be reached by alternative routes.

Now the writer, at the beginning of the second paragraph, returns to the metaphor of pilgrimage. Since life is a pilgrimage (goes the reasoning) and since our ultimate destination is one of two cities (Jerusalem or Babylon), then we ought to take care to map out the road by which such places are reached. Here another kind of authority, of the patristic variety (the reference to Augustine), is introduced to provide further support. Awareness, careful thought, superior effort – in a word, virtuous living – form the path to endless bliss, sinful living the path to endless pain. The emphasis then is not on pilgrimage as act but on pilgrimage as a way of figuring an internal reality. This metaphorical way of discoursing is an expression of an outlook which sees reality lying beyond or beneath the surface of sense impressions. Practical pilgrimage is of course not ruled out in this scheme of things, but pilgrimage is seen as essentially an inward movement of the soul to God.

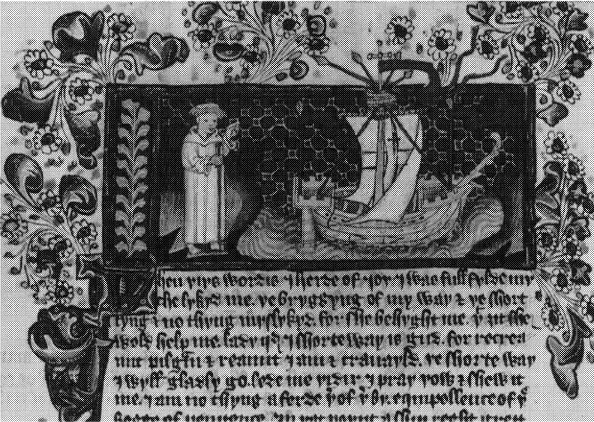

An image from a contemporary manuscript (Plate 1) will help to capture the doubleness of pilgrimage. (The writing beneath reads: ‘When these words I heard, of joy I was fulfilled; much liked me the abridging of my way and the shorting, and nothing misliked me …’). Look carefully at the picture and answer the following questions:

1. What does the figure on the left represent?

2. What associations does the sea have?

3. What is the significance of the ship?

4. What is the narrative content of the picture?

5. How does the picture illuminate the passage from the Mirror?

Ostensibly, this is a picture of a pilgrim, staff in hand, about to embark on a ship in order to continue with the next stage of his journey. We might also note that he is tonsured, and dressed in a habit, signifying that he is a monk; and that the ship’s mast is topped by a crucifix (an emblem of which also appears on the sail), surrounded by spears. Perhaps they are associated with the crucifixion image as instruments of Christ’s death.

Plate 1: Pilgrim’s progress.

Thus a close examination of the picture indicates that it is enigmatic, that it has a symbolic dimension, one that is suggested by the title of the text in which it appears, The Pilgrimage of the Life of the Manhode, an English translation made in the early 1400s of Guillaume de Deguileville’s Pèlerinage de la vie humaine (1330–31), part of which was translated by Chaucer as his ABC, a prayer to the Virgin. In it the author, presenting himself as a monk, describes how he had a dream of a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It turns out to be a medieval Pilgrim’s Progress: en route, the dreamer encounters temptations and setbacks, as well as help and encouragement. Towards the end of his journey, a figure called Tribulation hurls him into the sea and, although he cannot swim, he keeps afloat by holding on to his pilgrim staff, the pommels of which signify Christ and the Virgin. Eventually he is rescued by Grace-Dieu (grace of God) who tells him that his progress t...