![]()

CHAPTER 1 Introduction

There is no future without risk.

Swiss Re (2004: 5), The Risk Landscape of the Future

He either fears his fate too much or his deserts are small, Who dare not put it to the touch to win or lose it all.

James Graham (1612–1650), Scottish general

In introducing one of finance’s most important papers, William Sharpe (1964: 425), recipient of the 1990 Nobel Prize in Economics, wrote:

One of the problems which has plagued those attempting to predict the behaviour of capital markets is the absence of a body of positive microeconomic theory dealing with conditions of risk.

From a slightly different perspective, Lubatkin and O’Neill (1987: 685) wrote: ‘Very little is known about the relationship between corporate strategies and corporate uncertainty, or risk.’ Although these and other authors have illuminated their topic, there is still no comprehensive theory of firm risk. This work is designed to help fill part of that gap.

In firms, ‘risk’ is not one concept, but a mixture of three. The first is what might occur: this is a hazard and can range from trivial (minor workplace accident) to catastrophic (explosive destruction of a factory); it is the nature and quantum of a possible adverse event. The second component of risk is its probability of occurrence: for some workplaces such as building sites, the chances of an accident may be near 100 per cent unless workers watch their step. The third element of risk is the extent to which we can control or manage it. Trips are largely within individuals’ control. But what about destruction of the workplace? Avoiding that is perhaps only practicable by forming some judgement about operations and standards, and keeping out of facilities which look lethal. To further complicate risk, these elements can be overlain by environmental influences, and the way risk is framed or presented.

Although risk does not have a theoretical place in corporate strategy, it is intuitively obvious that its influence on firm performance is such that it should be an important factor in decision making. Every year, for instance, it seems that a global company is brought to its knees in spectacular fashion by an unexpected event: Barings Bank and Metallgesellschaft, Texaco and Westinghouse, Enron and Union Carbide are huge organizations that were pushed towards (or into) bankruptcy by strategic errors.

Even without a disaster, corporations are extremely fragile: the average life of an S&P 500 firm is between 10 and 15 years (Foster and Kaplan, 2001); and the 10 year survival rate for new firms which have listed in the US since 1980 is no more than 38 per cent (Fama and French, 2003). Company fragility seems to be rising. Of the 500 companies that made up the Fortune 500 in 1955, 238 had dropped out by 1980; in the five years to 1990, 143 dropped out. Thus the mean annual ‘death rate’ of the largest US companies rose from 0.2 per cent in 1955–1980 to 5 per cent in 1985–1990 (Pascale, 1990). My own research has shown that out of 500 companies in the S&P 500 Index at the end of 1997, 129 were no longer listed at the end of 2003 due to mergers (117 firms), bankruptcy (7) and delisting (5): the annual death rate was 4.3 per cent.

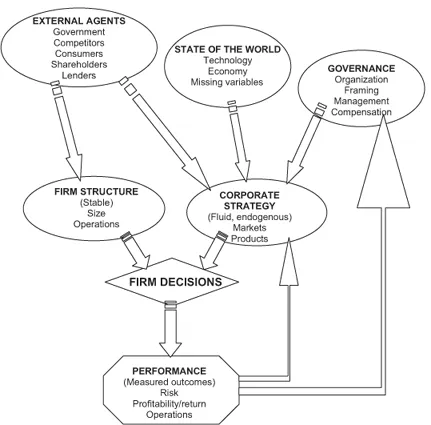

Risk is so pervasive and important that its management offers the prospect of great benefit. To set the scene, Figure 1.1 shows my model of firm risk and its key working assumptions. In brief, observable corporate outcomes – such as profitability and risk – are impacted by relatively stable structural features of the firm that are largely determined exogenously (such as size, ownership and operations); and by more fluid strategic factors that are largely endogenous (such as markets, products and organization structure). These factors, in turn, are shaped by the influences of Politics, Economy, Society and Technology (PEST), and by competitors, consumers and the investment community. External pressures encourage firms to change their tactics and strategies and thus induce moral hazard; and performance – particularly below an acceptable level – can feed back to induce changes in strategy. This is a resource and knowledge-based view of the firm, with risk as a key variable in determining shareholder value.

This framework will be followed in developing a body of theory behind firm risk, and showing how it can be managed strategically to add value. The figure gives a new perspective to corporate performance with its contention that risk and return are determined by a set of common underlying factors in the firm’s structure and strategy. This explains the conventional assumption of a direct causal link between risk and return, which seems true across most disciplines. The model here goes further, however, in proposing that risk shares the same drivers as other performance measures, including returns. As we will see, this makes any return-risk correlation spurious because each arises independently from shared underlying drivers. Most importantly, this negates a common management and investor assumption that taking greater risk will lead to higher returns.

Figure 1.1 Model of firm risk

The concept of risk throughout the book is firm risk. Although measured in different ways, it is a probability measure that reflects the actual or projected occurrence of unwanted or downside outcomes that arise from factors that are unique to a firm or a group of firms. Thus it excludes systematic risks that arise from market-wide factors, such as recessions or equity market collapse. Firm risk incorporates idiosyncratic risk (sometimes called non-systematic or diversifiable risk) from finance which is the standard deviation of returns that arise from firm-specific factors and can be eliminated by diversification. Firm risk is also measured by loss in value, and by the frequency of incidents that contribute to value loss.

The analysis combines the perspectives of corporate finance and corporate strategy, and uses ‘risk’ with its dictionary meaning as the possibility of an adverse outcome. This is the way that risk is understood by managers, and also by key observers such as the Royal Society (1992) which defined risk as ‘the chance that an adverse event will occur during a stated period’. However, we will see that the exact definition of risk is not critical because its various guises – operational risk, downside risk, variance in accounting measures of performance, and so on – are correlated (as would be expected from Figure 1.1).

The topic of corporate risk is important economically. I agree with Micklethwait and Wooldridge (2003) that the world’s greatest invention is the company, especially as companies generate most of the developed world’s wealth and produce most of its goods and services. Understanding how risk acts on their output offers the promise of a quantum improvement in economic performance, which – in keeping with Sharpe – has languished without explanatory theory.

Risk in firms is the downside of complex operations and strategic decisions: modern companies run a vast spectrum of risks, with many of such magnitude as to be potential sources of bankruptcy. Because the nature and quantum of risk shift along with changes in a firm’s markets, technology, products, processes and locations, risk is never stable or under control, and hence is challenging to manage. Fortunately, though, risk shares many of the attributes of other managerial concepts that focus on value, including knowledge, quality and decision efficiency. Improving any one of these often improves the others, so risk management is a powerful tool in improving firm strategy and performance.

Conventional risk management techniques assume that companies face two general types of risk. The first is operational and arises in the products and services they produce, and within their organization and processes. These risks are managed mechanically using audits, checklists and actions that reduce risk; the best approaches are broad ranging and strive for Enterprise-wide Risk Management which DeLoach (2000: xiii) in a book of that name defined as:

A structured and disciplined approach: it aligns strategy, processes, people, technology and knowledge with the purpose of evaluating and managing the uncertainties the enterprise faces as it creates value.

The second type of risk that companies face is financial and is sourced in the uncertainties of markets, and the possibility of loss through damage to assets. These are typically managed using market-based instruments such as insurance or futures.

This leads to four approaches to managing business risks that were first categorized by Mehr and Hedges (1963): avoidance; transfer through insurance, sharing or hedging; retention through self-insurance and diversification, and reduction through Enterprise Risk Management (ERM). These techniques have proved immensely successful in relation to identifiable hazards – such as workplace dangers and product defects – which might be called point-sourced risks. As a result of tougher legislation and heightened stakeholder expectations, the incidence of these risks has fallen by between 30 and 90 per cent since the 1970s. Conversely the frequency of many firm-level strategic risks – crises, major disasters, corporate collapses – has risen by a factor of two or more in the same period. This suggests that conventional risk management techniques have reached a point of diminishing returns: they are effective against point-sourced risks, but unable to stem the steady rise in strategic risks.

Despite this, corporate risk management remains unsophisticated. For a start, finance and management experts have little interest in any cause-and-effect links between risk and organizations’ decisions. Finance ignores risks that are specific to an individual firm on the assumption that investors can eliminate it through portfolio diversification, and thus ‘only market risk is rewarded’ (Damodaran, 2001: 172). But this argument is not complete. For instance, market imperfections and frictions make it less efficient for investors to manage risk than firms. Secondly firms have information and resources that are superior to investors and make them better placed to manage risk. Third is the fact that many risks – particularly what might be called business or operational risks – only have a negative result and are not offset by portfolio diversification. Risk management should be a central concern to investors, and exactly this is shown by surveys of their preferences (for example, Olsen and Troughton, 2000).

Similar gaps arise within management theory which rarely allows any significance to risk and assumes that decision making follows a disciplined process which defines objectives, validates data, explores options, ranks priorities and monitors outcomes. When risks emerge at the firm level, it is generally accepted that they are neutered using conventional risk management techniques of assessing the probability and consequences of failure, and then exploring alternatives to dangerous paths (Kouradi, 1999). Systematic biases and inadequate data are rarely mentioned; and the role of chance is dismissed. For instance, the popular Porter (1980) model explains a firm’s performance through its relative competitive position which is an outcome of strategic decisions relating to markets, competitors, suppliers and customers. Risk has no contributory role, and is dismissed by Porter (1985: 470) as ‘a function of how poorly a strategy will perform if the “wrong” scenario occurs’. Oldfield and Santomero (1997: 12) share a similar view: ‘Operating problems are small probability events for well-run organizations.’ Even behavioural economics that has recently been applied to firm performance (for example, Lovallo and Kahneman, 2003) generally only attends to the shortcomings of managers’ cognitive processes. This, however, completely ignores the huge amount of effort that most firms and managers put into risk reduction.

Another important weakness in risk management is that theory and practice are largely blind to the possibility that managing risks can lift returns. As a result sophisticated risk management practices are uncommon in firms. An example is the archetypal risk machines of banks and insurance companies. Neither considers the full spectrum of business risks being faced by their customers and shareholders: both look to statistics and certainty, rather than what can be done to optimize risk, and concentrate on either risk avoidance or market-based risk management tools. Thus an otherwise comprehensive review of risk management in banking by Bessis (1998) devoted just a few pages to operational risks.

Corporate risk management is equally weak, largely because it tends to be fragmented. Take, for instance, a typical gold mining company, whose most obvious exposures are operating risks to real assets. Control is achieved qualitatively, through some combination of reduction, retention and sharing that becomes a reductionist process of loss prevention. Responses are managed by health and safety professionals, through due diligence by senior management, and via inspections by employees and auditors. Staff are trained like craftsmen through an apprenticeship and rely on tacit knowledge because the firm’s operating risks are often complex, hidden and uncertain.

The miner also faces another set of risks that affect its capital structure and cash flow, but they are managed quite differently. A treasury expert will quickly identify and quantify them, accurately estimate costs associated with alternative management strategies, and make clear recommendations on tactics. Well-recognized quantitative tools are portfolio theory, real options and risk-return trade-offs. These risk managers have formal training, apply explicit knowledge and use products as tools for risk management.

Shareholders, however, do not distinguish between losses from a plant fire or from an ill-balanced hedge book. They know from bitter experience that badly managed business risks can quickly bring down even the largest company. HIH, One Tel and Pasminco were well-regarded firms with blue riband directors that failed due to weak risk management. BHP, Fosters, Telstra and other firms did not go broke, but have destroyed billions of dollars of shareholders’ funds through poorly judged risks. Risk should be managed holistically, not in silos.

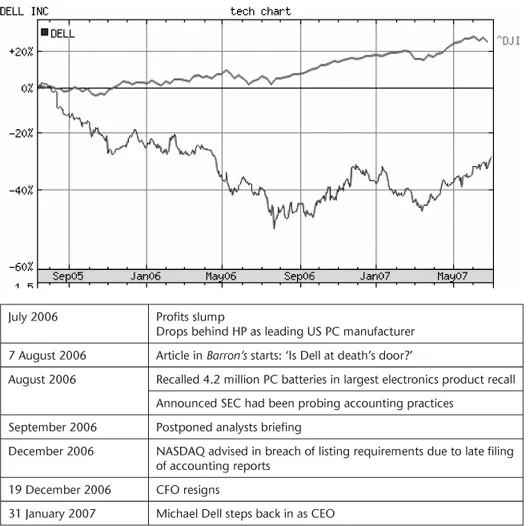

An important trend which we develop at length in the next chapter is that strategic risks – crises, major disasters, strategic blunders – are becoming more common, with growing impacts on shareholder value. A good example is shown in Table 1.1 using the example of one-time market darling Dell Inc. In the year to August 2006, as the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose, the share price of Dell fell 45 per cent after the company’s profits dropped, market share slipped and criticisms became widespread about neglect of customer service. In the following months the company was hit by the largest ever electronics product recall, a probe by the SEC into its accounting practices, and the threat of suspension following late filings of financial reports. A stream of executives left and company founder Michael Dell was forced to defend the CEO before firing him in January 2007 and dramatically resuming the position of Chief Executive.

Recurring crises of the type that enmeshed Dell are occurring under three sets of pressures. One is the growing complexity of systems: economies of scale, integration of manufacturing and distribution systems, and new technologies have more closely coupled processes so that minor incidents can readily snowball into major disasters. The second cause is deregulation and intense competition which have forced many firms to take more strategic risks in order to secure a cost or quality advantage. Given executives’ poor decision-making record, an increase in the scale and frequency of strategic risks leads to more disasters.

A third contributor to more frequent strategic risks is corporate re-engineering and expanding markets, and the need to maintain returns in an era of low inflation. As society and industry become networked, intangibles such as knowledge and market reach become more important and so usher in new exposures. Moreover, areas of innovation involving environment, finance and information technologies tend to be technically complex and enmeshed in their own jargon, which promotes yuppie defensiveness that deters even the most interested outsiders from exploring their risks. Too many high-risk areas and processes in firms fall by default to the control of specialists (often quite junior ones) because senior management – which is best equipped to provide strategic oversight – is unable to meaningfully participate in the evaluations involved.

Table 1.1 Dell Inc case study: Nature of firm risks

The confluence of these and other contributors to strategic risk explains why conventional risk management techniques have reached a point of diminishing returns: they can be effective against point-sourced risks, but are unable to stem the steady rise in firm-level risks. In short, conventional risk management techniques are simply inadequate to manage contemporary risks, and a new paradigm is required for risk management. That in a nutshell is the rationale for this book.

With ‘risk management’ so popular as a buzzword, it is timely to consider what it actually is. The concept was first introduced into business strategy in 1916 by Henry Fayol. But it only became formalized after Russell Gallagher (1956) published ‘Risk Management: A New Phase of Cost Control’ in the Harvard Business Review and argued that ‘the professional insurance manager should be a risk manager’. As new technologies unfolded during the 1960s, prescient business writers such as Peter Drucker (1967) garnered further interest in the need for risk management, and it became so obvious that US President Lyndon Johnson could observe without offence in 1967: ‘Today our problem is not making miracles, but managing miracles. We might well ponder a different question: What hath man wrought; and how will man use his inventions?’

Inside firms, elements of risk management emerged in the goals of planning departments, and its philosophy was fanned in students of operations research and strategic management. But not until the early 1980s did risk management became an explicit business objective. Then neglect evaporated with a vengeance. In a popular book Against the Gods, Peter Bernstein (1996: 243) argued: ‘the demand for risk management ...