eBook - ePub

Stone Worlds

Narrative and Reflexivity in Landscape Archaeology

- 476 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stone Worlds

Narrative and Reflexivity in Landscape Archaeology

About this book

This book represents an innovative experiment in presenting the results of a large-scale, multidisciplinary archaeological project. The well-known authors and their team examined the Neolithic and Bronze Age landscapes on Bodmin Moor of Southwest England, especially the site of Leskernick. The result is a multivocal, multidisciplinary telling of the stories of Bodmin Moor—both ancient and modern—using a large number of literary genres and academic disciplines. Dialogue, storytelling, poetry, photo essays and museum exhibits all appear in the volume, along with contributions from archaeologists, anthropologists, sociologists, geologists, and ecologists. The result is a major synthesis of the Bronze Age settlements and ritual sites of the Moor, contextualized within the Bronze Ages of southwestern and central Britain, and a tracing of the changing meaning of this landscape over the past five thousand years. Of obvious interest to those in British prehistory, this is a substantial presentation of a groundbreaking project that will also be of interest to many concerned with the interpretation of social landscapes and the public presentation of archaeology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stone Worlds by Barbara Bender,Sue Hamilton,Christopher Tilley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Introduction

Chapter One

Stone Worlds, Alternative Narratives, Nested Landscapes

This is a book about landscape. About embodied landscapes, about the way in which people engage with the world around them, how they make sense of it, how they understand and work with it. And how it works on them. It is primarily about prehistoric landscapes, but also about contemporary ones.

It is about a project that involves both archaeologists and anthropologists. It also involves sociological projects, art projects, an exhibition, and a website. It attempts to question and work across disciplinary boundaries.

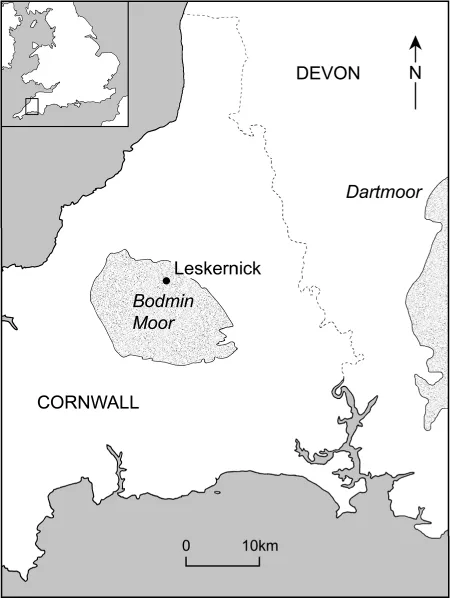

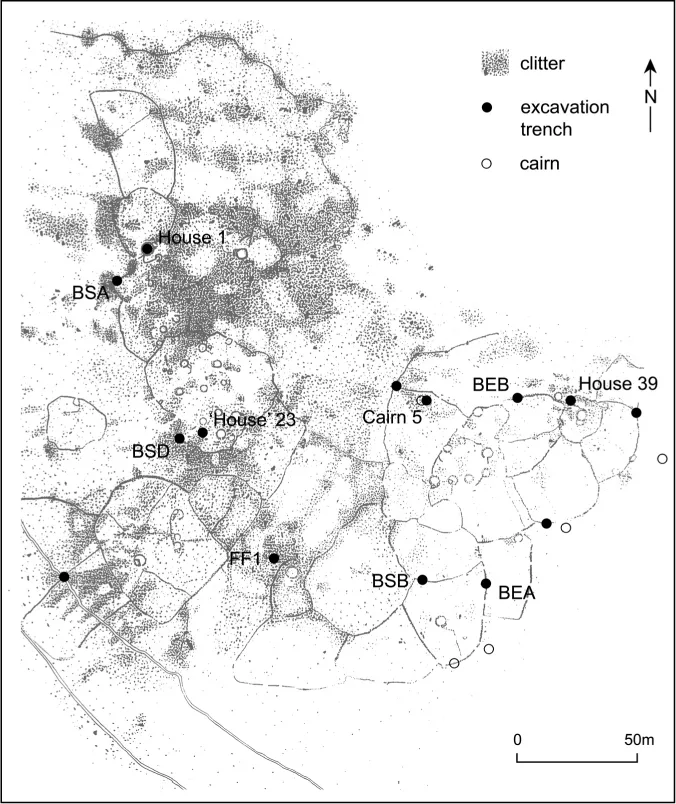

It is the culmination of five summers’ work at Leskernick, a small hill in the northern part of Bodmin Moor in Cornwall, in which the archaeologists excavated 21 trenches, and the anthropologists surveyed both at Leskernick and across the moor (Figure 1.1).

In hindsight, the project began when Chris Tilley, who works in both the Department of Anthropology at University College London (UCL) and at the neighbouring Institute of Archaeology (also part of UCL), undertook a survey of Bodmin Moor in 1994. His work focussed on ritual sites: the stone rows and circles, the cairns, and hilltop enclosures. His intention was to discover how they related to each other and to features in the landscape, most particularly the high tors. He wanted to show the link, both cause and effect, between people’s symbolic evocation of their world and their experience of living in and moving around the landscape (Tilley 1995). In his work on the moor, Chris avoided the dense clusters of house circles, partly because it was almost impossible to survey them on his own and partly because his attention was drawn to the overtly ritual monuments.

fig. 1:1 Location map: Leskernick, Bodmin Moor, Cornwall.

CT (1994): I could see the settlement area from the cairn – a massive tangle of stones – and decided to avoid it. It seemed impenetrable, aloof, impossible to investigate compared with the stone circles and stone rows where I had a methodology and knew what I was to do. I took pity on a solitary wind-blown hawthorn tree eking out a solitary existence on the lower slopes of the hill among the clitter spreads. Why should anyone want to live in this desert of stone?

The houses seemed, at first glance, to be more mundane, more everyday. But this division between the sacred and profane, or the secular and the spiritual, is a contemporary one.1 It is a distinction that is neither valid in our own world, where the most mundane activities and places are infused with ritual, nor is it appropriate for other times and places. If our work on the Leskernick hillside has done nothing else, it has shown, beyond a shadow of doubt, that the domestic is as ritualised, as symbolic as any lonely cairn or stone row.

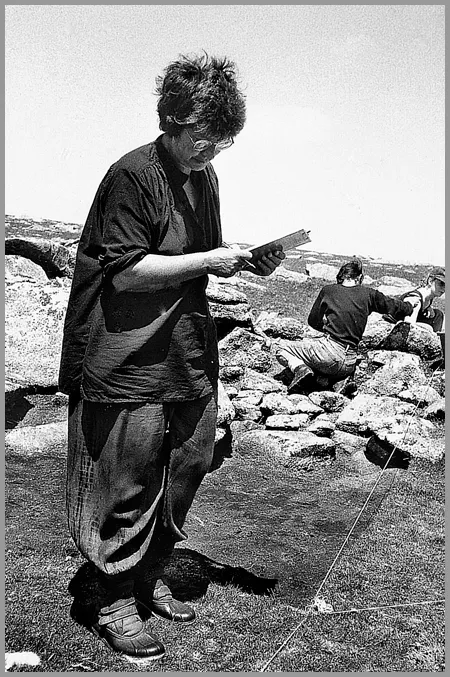

Early in 1995, recognizing that there was something missing in his story, Chris talked with Sue Hamilton (Institute of Archaeology, UCL) and Barbara Bender (Department of Anthropology, UCL) about the possibility of working together on the moor (Figure 1.2). Chris mentioned the site of Leskernick, and he and Sue discussed what sorts of excavations would be practicable and in what order they might be undertaken. They ascertained, with some relief, that Leskernick had not been scheduled and that Dave Hooley, the monuments protection officer for English Heritage, might look favourably upon an application to excavate. They also got in touch with the Cornish Archaeological Unit, some of whom had been involved in the creation of the prodigiously detailed map of the settlement (Johnson and Rose 1994). They too seemed happy that we would work on the moor.2

And so, on a fine spring morning, the three of them walked across the moor to Leskernick (Figure 1.3).

fig. 1:2 Clockwise starting top left: Chris Tilley; Unknown Sleeper; Sue Hamilton; Barbara Bender.

fig.1:3 View of the southern hillside of Leskernick taken from Codda. Looking carefully the enclosures and house circles begin to emerge. Photo J. Stafford-Deitsch.

BB (1995): A warm milky day, the path worn into the granite. Chris inducting us into the names of places. Leskernick: a gentle hill, with a great rock tumble, just possible, from a distance – knowing what to look for – to see the occasional enclosure wall. On the lower slopes and the plain, no stones, just tussocky grass. Occasionally, as we walked, we’d stumble over slightly elevated grassy square shapes. ‘Medieval,’ Chris said. Most times I didn’t notice them. Equally, I guess I wouldn’t have noticed the stone row. Such very small stones, and half covered with matted grass. Chris showed us the mound and then the stone row which led off and away across a gully. … A strong sense of not ‘seeing’ much …

SH (1995): As we came over Codda Hill Tor the southerly slopes of Leskernick Hill came into view. The prehistoric settlement appeared as a patterned mass of stones merging into scree-strewn hillside where loose clitter and earth-fast boulders were anarchically juxtaposed. … The hillside looked fractured and grey against the smooth yellow-green moor below.

On the sides of the hill were two extensive houses clusters and numerous sinuous walled enclosures (Figure 1.4). To the south, on the plateau below the hill, was a small stone row and two stone circles. At the top of the hill was a large propped stone and a large ruined cairn. Here, then, were all the elements for an integrated project involving both daily life and more ceremonial occasions.

It was a place to capture the imagination. It was also, as Chris had discovered earlier, rather daunting.

fig. 1:4 Map of Leskernick showing the clitter, settlements, enclosures, cairns, and locations of the excavation trenches. Only the excavation trenches discussed in the text are labelled (BS=boundary section; FF=field feature; BE=boundary entrance). All of the excavation trenches are discussed in Hamilton and Seager Thomas (in prep). The map is adapted from that produced by the Royal Commission of Historic Monuments (England).

SH (1995): It was easy to feel ‘lost’ in the stone row area. … I felt at home in the settlement area. We searched for some cairns on the perimeter of the settlement. Without a large-scale plan it was difficult. The ‘natural’ clitter played tricks, mimicking mounds and enclosure boundaries, or was it vice-versa?

Already, in that first encounter, people’s different perceptions of place and landscape began to surface.

BB (1995): Sue worries about how to tie an excavation trench to the three stones that make up the terminal of the row. Chris shows us the way in which, at a certain juncture as you walk the stone line, Rough Tor comes into sight. The Elder inducting the juniors.

Up to the settlement: slowly bits of wall become clearer … and a small cairn with a cist … then three round small hut floors. We talk about entrances and what they would have seen. Of wooden structures, water availability. Sense that Chris becomes uneasy if the conversation becomes too ‘functional’.

Having got a hesitant feel of the place, we agreed that during the first – modest – season the excavation would focus on the western terminus of the stone row that lay below and to the south of Leskernick Hill. The fallen stones at this end were much larger than along the rest of the row and, quite apart from discovering their original placement, there was the possibility that there might be ritual offerings. Meanwhile, the survey team would begin to work on the hillside, familiarising itself with the settlements and enclosures and checking the orientation of the house doors. The surveyors wanted to find out whether the sort of linkages that Chris had found between ritual constructions – long mounds, stone rows, and so on – and particular places in the landscape such as the high tors also held good in more everyday settings.

In the summer of 1995 the group consisted of the three directors and nine students.

BB (1995): We were camping quite close to Jamaica Inn and so we used to walk in from the southern part of the moor. It was a fantastic walk, down a very old, deeply entrenched track, over a ford. … Then, after half a mile or so, the path gave out and we walked for about a hundred metres until, cresting a shallow incline, we saw, across the moor, the low stone grey hill of Leskernick.3

Slowly, we began to work our way into the site, physically, intellectually, and emotionally. In that first year we all tried our hand at everything. A year later, the numbers had increased, we began to bring specialists on board, and, as people became more knowledgeable and more passionate about either the excavations or the surveying, fairly inevitable divisions of labour emerged (chapter 11). There were nine on site in 1996, 17 in ‘97, 25 in ‘98, and 31 in 1999.

During the second season (1996), the archaeologists finished work on the terminal to the stone row and began work on the settlement. Over the course of four summers (1996-99), they excavated three houses and adjacent outside areas, a ‘cairn’, numerous sections of enclosure wall including entrance areas and wall junctions, the area in front of the ‘Shrine Stone’, and parts of the North Stone Circle. Meanwhile, the surveyors, having spent their first year looking outwards from the house doors towards the surrounding hills, went on to survey each and every house and field enclosure on the hill.

BB (16 June 1996): In the first year we focussed on a structured universe. This year we found out much more about the way it was played out – worked out – through complex changing … activities and actions. …

Working on the southern settlement, [we] felt more and more strongly that the houses were not all lived in at the same time. Some were ruined whilst others were being built. There were also spaces and places that had already accumulated meaning, … [places where] the walls took appropriate respectful avoiding action. … More obviously, the enclosures were a process of accretion, abandonment and change. In one field it seems that an old wall had gone out of use, and had been robbed to make a new stout wall enclosing a larger area. In the western settlement, Chris and Wayne found more dramatic evidence of this process, with houses being decommissioned and then sometimes re-used as cairns. Life on the hillside, over hundreds of years, was complicated and nuanced.

And then, in the last two seasons, they moved out into the larger landscape.

In the first half of the book, chapter 2 discusses the nature of the moor, chapters 4-9 chart the progress of the archaeological excavations and anthropological survey work on and below the hill, and chapter 3 looks at the methodologies involved. Towards the end of the book, chapters 16-18 open to the wider prehistoric landscape.

It was always intended that the project would be about contemporary as well as prehistoric landscapes. Because we can only come to the past through the present, it seemed important to spend time trying to understand our attitudes, preconceptions, and engagement with the world around us. The anthropologists – often with help from the archaeologists – worked on, and with, the contemporary landscape, creating art installations and a travelling exhibition. Two anthropologists spent parts of two seasons at Leskernick looking at the ways in which we, in the present, engaged with the landscape, at our material culture, and at the social practices involved in the work we undertook. Another anthropologist created the Leskernick website. These contemporary preoccupations form the centre part of the book, chapters 10-15.

Prehistoric Landscapes

By the end of the summer of 1999 when the last trench was back-filled and hill and caravan park had reluctantly been left behind, we had an enormous amount of data. How were we to present these? We wanted this to be a book that opened in many directions, that crossed disciplinary boundaries, and that questioned long-established conventions on how scientific work should be presented. We did not want to write a monograph or a book with endless appendices. We wanted to write something that was readable, but it has to be admitted that, with 50 house circles and many kilometres of enclosure wall, not to mention the innumerable contexts uncovered in excavation, and the details of other settlements across the moor, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: Introduction

- Part Two: The Present Past

- Part Three: The Present Past

- Part Four: Beyond The Hill

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors