![]()

1

An unstable, stable nation? Climate, water, migration and security in Syria from 2006–2011

Francesco Femia and Caitlin Werrell

Introduction

From 2006–2012 Syria experienced one of the worst extended droughts in its history. This drought, coupled with natural resource mismanagement, demographic dynamics and overgrazing in certain areas, contributed to a massive displacement of agricultural and pastoral peoples. Despite these dynamics and other existing underlying socio-political and economic grievances, key actors in the international community largely considered Syria to be a stable country relative to other nations in the Middle East and North Africa that experienced significant social unrest in the so-called Arab Uprisings (Butters 2011; Mann 2012). This chapter explores the climate and natural resource elements of Syria’s state fragility, the phenomenon of governments across the international community misdiagnosing the probability of Syrian instability in 2011 and the possible pathways forward for the country and the international community in addressing these risks.

The climate-water-natural resource management nexus in Syria from 2006–2012

The factors that contributed to the popular uprisings in Syria in 2011 are very complex and remain little explored. As with all conflicts, a confluence of ultimate and proximate causal factors intersect, resulting in discontent turning to revolt, and governments either managing or suppressing that revolt, collapsing or something in between. In the case of Syria’s popular revolt, which began most visibly in the southern rural town of Dara’a in March 2011 (PBS 2011), political, economic, ethnic, sectarian and religious grievances, as well as inspiration from uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, have been offered as contributing factors to the collapse of security in the country.

Less attention has been paid, however, to significant agricultural, pastoral, environmental and climatic changes in Syria. Combined with the mismanagement of water and food resources by the al-Assad regime, which between 2007 and 2011, these changes converged to precipitate a severe humanitarian crisis. Despite UN reports highlighting the crisis, it was barely noticed by the international community, in part due to the Syrian government’s attempts to prevent reporters from accessing internally displaced peoples (Worth 2010). This study represents an update of a previous study on the subject (Femia and Werrell 2012).

A climate-exacerbated drought on top of a drought

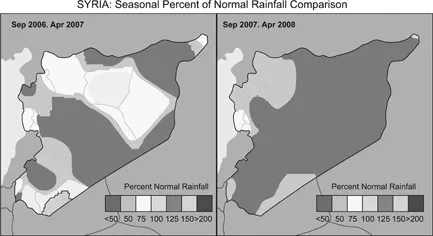

From 2006 to 2012, Syria experienced one of the worst long-term droughts and most severe set of crop failures and livestock devastation in its history of records, with the period from 2009–2012 registering as the most extreme drought conditions across a number of regions (Werrell et al. 2015, p. 31). From 2007 to 2008, the severe drought affected 97.1 per cent of Syria’s vegetation (Figure 1.1) (Wadid et al. 2011, p. 11). This drought also followed on the heels of another of Syria’s most severe droughts in modern history, which took place from 1999–2000, and affected 329,000 people (Werrell et al. 2015, p. 31).

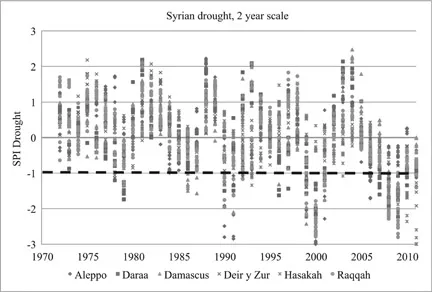

Figure 1.1 Drought, two-year scale, Syria from 1970 to 2011. Calculated by Standard Precipitation Index (SPI), −1 or below signifies drought (−1 = moderate drought; −2 = extreme drought)

Recent evidence suggests that the probability of such a severe-to-extreme drought period from 2006–2012 increased as a result of anthropogenic climate change. A study by Hoerling et al. (2012) found strong evidence that winter precipitation decline in the Mediterranean littoral and the Middle East from 1971 to 2010 was likely due to climate change, with the region experiencing nearly all of its driest winters since 1902 in the past 20 years (Figure 1.2) – a problematic phenomenon given that the region receives most of its annual rainfall in the winter. This trend of precipitation decline can also be seen quite clearly in the Standard Precipitation Index (Werrell et al. 2015, p. 31). The authors determined that half of this drying magnitude can be explained by anthropogenic greenhouse gas and aerosol forcing, as well as increases in sea surface temperature (Hoerling et al. 2012).

Figure 1.2 Syria: Seasonal per cent of normal rainfall, comparison 2006–2008 (USDA 2008)

More recently, a study by Kelley et al. (2015) found that the extreme drought in Syria from (2007–2010) was two to three times more likely to be a result of anthropogenic rather than natural climatic changes (Kelley et al. 2015).

Natural resource mismanagement and desertification

The reasons behind the collapse of Syria’s farmland and rangeland extend beyond the drought, and the climate change drivers that increased its likelihood. A complex interplay of variables, including natural resource mismanagement, demographic dynamics and overgrazing interacted with changing climatic conditions to enable that outcome (Femia and Werrell 2012).

First, poor governance by the al-Assad regime compounded the effects of the drought, which contributed to water shortages and land desertification. The al-Assad government, like many of its predecessors, heavily subsidised water-intensive wheat and cotton farming (more than 50 per cent of which was grown in the al-Hassakeh governorate (Matlock 2008), which was incidentally hardest hit by the drought). A focus on water-intensive crops, coupled with the widespread use of inefficient irrigation techniques, such as ‘flood irrigation,’ wherein nearly 60 per cent of water used is wasted, placed significant strains on Syria’s water resources (IRIN 2010a). This dynamic stood in contrast to a number of other nations in the Middle East and North Africa, who, for example, imported most of their wheat. In fact, 9 out of the top 10 wheat importers in the world can be found in the Middle East and North Africa (Sternberg 2013, p. 13).

In the face of water shortages that flowed from water-intensive agricultural practices, the previous drought from 1999–2000 and population pressures, farmers sought to increase supply by turning to the country’s groundwater resources. Syria’s National Agricultural Policy Center reported a 63 per cent increase in wells tapping aquifers from 1999 to 2007 (Sticklor 2010). This pumping ‘caused groundwater levels to plummet in many parts of the country, and raised significant concerns about the water quality in remaining groundwater stocks’(Sticklor 2010). This wheat and cotton production, coupled with the severe–extreme drought, significantly diminished the water table in the country.

On top of water resource mismanagement, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that the overgrazing of land, and a rapidly growing population, compounded the land desertification process in Syria (IRIN 2010b). In a study from 2014, De Châtel (2014) also determined that overgrazing in areas of Syria affected by drought may have been a key driver of desertification (De Châtel 2014).

Water resource management in neighbouring countries, particularly Turkey, may also have played a role in Syria’s water insecurity during the decade prior to the uprising, though likely not as significant a role as the al-Assad government’s own policies. In particular, from 1990–2010, average annual flows of the Euphrates River, as measured close to the Turkish border in Jarabulus, were significantly lower than the average annual flows from 1937–1990. This decline coincided with the 1992 completion of the Ataturk Dam on the Euphrates in southeastern Turkey (Gleick 2014, p. 5).

Internal mass displacement

This climate-drought-natural resource management nexus in Syria ultimately precipitated a significant and under-reported humanitarian disaster in the country from 2006–2011, prior to the outbreak of widespread popular revolt against the al-Assad government.

Of the most vulnerable Syrians dependent on agriculture, particularly in the northeast governorate of Hasakah, 75 per cent experienced total crop failure (Gleick 2014, p. 15). On average, pastoral peoples in the northeast of the country lost around 85 per cent of their livestock (Worth 2010). As of 2010, the combined impact on agricultural and pastoral lands affected at least 1.3 million people (Werrell et al. 2015, p. 32).

According to a report from the New York Times, the al-Assad government attempted to prevent international observers and journalists from accessing people affected by the collapse of farmland and rangeland (EM-DAT 2016). Nonetheless, from 2009 through 2011, some institutions of international agencies and non-governmental organisations had begun to identify the humanitarian crisis unfolding in Syria. In 2009, both the United Nations and International Red Cross reported that over 800,000 Syrians had lost their livelihoods as a result of the agricultural and rangeland collapse (IRIN 2009). By 2011, it was estimated that one million Syrians had been left extremely ‘food insecure’ by the collapse (Wadid et al. 2011, p. 5). Another estimated that two to three million people had been driven into extreme poverty, approximately 9–13 per cent of the country’s population (Worth 2010).

This loss of livelihoods led directly to a mass displacement of farmers, herders and agriculturally-dependent rural families, a majority of whom moved to urban areas in search of employment opportunities (Wadid et al. 2011, p. 8). One estimate suggested that between 1.5 and 2 million people had been displaced (Mohtadi 2012). In October 2010, the a UN estimate that 50,000 families migrated from rural areas just that year, following the hundreds of thousands of people that had migrated to urban areas during the previous years of the drought (Worth 2010). In January 2011, it was reported that crop failures just in the farming villages around the city of Aleppo drove roughly ‘200,000 people from rural communities into the cities’ (Nabhan 2010). This occurred while Syrian cities were already coping with influxes of Iraqi refugees since 2003, as well as a steady stream of refugees from Palestinian territory (UNHCR 2010). Crumbling urban infrastructure, a phenomenon that preceded the drought, combined with these population pressures and contributed to a significant decline in per capita water availability in urban areas (IRIN 2010a).

Interaction of natural resource stress and socio-political dynamics

The stresses that flowed from drought conditions, as well as water and land mismanagement by the al-Assad regime, existed in the context of a range of socio-political grievances among non-Alawite Arab and Kurdish populations in rural areas of Syria, particularly in the north and south. For example, anecdotal evidence suggests that well-drilling contracts were often awarded by the al-Assad government on sectarian grounds, favouring Alawite and other Shiite populations over others (“Anonymous” 2013).

The rural farming town of, the focal point for protests in the early stages of the opposition movement in 2011, was home to all of the stresses detailed above. Dara’a had been significantly affected by five years of drought and water scarcity (PBS 2011). The town also hosted a population that had been largely ignored by the al-Assad government, not least due to sectarian differences (Paralleli 2011).

Recent research has also made the case that discontent among a number of tribal populations displaced by the drought, a dramatically declining water table and underdevelopment played an important role in tribal uprisings, despite attention being paid primarily to sectarian drivers of unrest (Dukhan 2014). According to Syrian researcher Haian Dukhan:

the collapse of the rural economy of tribal communities in the south and east of Syria during Bashar al-Assad’s regime due to drought, lack of development projects and the mismanagement of al-Badia resources ignited the Syrian uprising to start in tribal regions.

Lastly, anonymous, unpublished interviews with tribal peoples who were displaced by the drought, and migrated to suburbs of Damascus and Homs, describe evidence of social tensions. This includes tensions between tribespersons from Hassakeh (particularly the Jabbour and Tay tribes) and residents of the Hajr Aswad suburb of Damascus, as well as sectarian tensions between displaced members of the Fwaira and Nu’im tribes and Alawite residents of the Baba Amr suburb in Homs (Dukhan 2015).

Though the lines of causality remain difficult to disentangle, it is reasonable to suggest that the combination of climate, drought, natural resource mismanagement, internal mass displacement of farmers and herders and sectarian grievances in Syria, coupled with knowledge of the recent revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, played a role in fraying the social contract between a range of rural and urban populations in the country and the seemingly ‘stable’ al-Assad government (Shadid 2011).

Misdiagnosed: Syria’s unstable stability

Despite the climate, water and food insecurities in Syria detailed earlier, and despite the mass displacement of people that followed, key actors in the international community, including the US government, seemed largely surprised by the Syrian uprisings that began in 2011. For example, the US Deputy Secretary of State during the initial wave of the Arab Uprisings, James Steinberg, was very clear about the fact that no one in a position of authority within the US foreign policy infrastructure considered Syria to be a likely candidate for significant political unrest. In an interview, Steinberg highlights the fact that Syria sat at th...