Introduction and background

This chapter explores the development of water, energy and food as sectors and how they have come into conflict at the intergovernmental level in relation to the global sustainable development agenda set in Rio in 1992, followed by the development at the CSD, and revisited and developed further in New York at Rio+5 (1997) and in Johannesburg at Rio+10 (2002) and Rio+20 (2012). It looks especially at how, as Rio+20 approached, there was an increased realization that these three sectors needed to be viewed in an interlinked way – a Nexus perspective. In the post Rio+20 phase, within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Open Working Group (OWG) strong voices promoted the idea that a Nexus perspective should be reflected in the targets and indicators under the relevant sector goals.

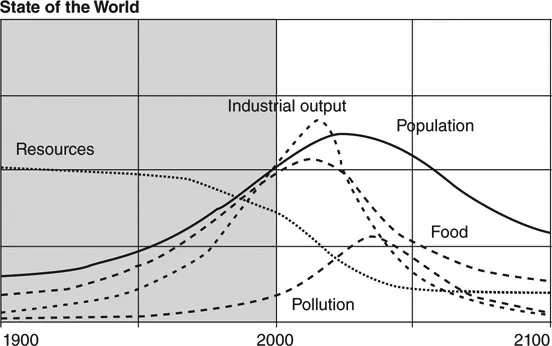

Fifteen years into the new millennium and well into the second century of ordered international relations under a single mechanism, i.e. the United Nations, it became clear that the predictions that were made in preparation for the first United Nations (UN) Conference on Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972 have largely come to pass. The stage for Stockholm was set by three ground-breaking reports. One of these was the Club of Rome’s ‘Limits to Growth’ (LTG) that modelled and projected five variables (Figure 1.1): world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion.

Adopting a new approach to alignment, which does not immediately fit with the international policy machine, or indeed the machinery of the UN’s member states which it largely reflects, is a significant risk that is not to be undertaken lightly. So why bother?

Among the future scenarios explored in Limits to Growth, scenario 1 reflects business as usual: the world proceeds in a traditional manner without any major deviation from the existing economic policies pursued during most of the twentieth century. Population and production increase until growth is halted by decreasing access to non-renewable resources. Increased investment is required to maintain resource flows. Finally, a lack of investment funds in the other sectors of the economy leads to declining output of both industrial goods and services. Food and health services are reduced, decreasing life expectancy and raising average death rates (Meadows et al., 1972).

Figure 1.1 Limits to Growth: Business as Usual.

The report projected that the trends of all five variables lead rapidly to a point of environmental, economic and social collapse. Limits to Growth caused widespread controversy when it was published. Thirty-five years later, Graham Turner of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Australia produced “A Comparison of ‘The Limits to Growth’ with Thirty Years of Reality” (2008) which examined the 1972 predictions of the Club of Rome with observed events. Chillingly, he found that predictions and observed events were consistent with the world’s path through the early twenty-first century.

In 2014, Graham Turner concluded that:

Regrettably, the alignment of data trends with the LTG dynamics indicates that the early stages of collapse could occur within a decade, or might even be underway. This suggests, from a rational risk-based perspective, that we have squandered the past decades, and that preparing for a collapsing global system could be even more important than trying to avoid collapse.

(Turner, 2014)

Short history of how we got here

The 1972 Stockholm Conference reflected emerging Western concerns about the combined effects of an increasing global population, the finite or apparently finite nature of several critical resources, and early signals of humankind’s ability to disrupt planetary systems through intent, pollution or resource use. One of the significant outcomes of the conference was an agreement to establish a new UN organ, the Environment Programme (UNEP). The UNEP would play a significant role as custodian of the environment, establishing UN conventions such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 1973), the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS, 1979), the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer (1985), and the Regional Seas Conventions. These were some of the first environmental conventions. They did represent a substantive uptick in international attention to environmental concern.

At the ten-year review of the Stockholm Conference, the Canadian government suggested that a UN Commission on Environment and Development was required to balance the need for economic development with the protection of the environment. In 1983 the UN General Assembly established the World Commission on Environment and Development, popularly known as the Brundtland Commission after its Chair, the Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland. The Commission produced a report entitled ‘Our Common Future’ for the UN General Assembly in 1987, which would be the first UN document to define sustainable development as:

development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

(UN, 1987)

This definition played to the growing concern about climate change. One of the most significant developments in the 1980s had been the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as a result of World Climate Conferences that had been held under the joint auspicious of the UNEP and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The first Assessment Report (1990) from the IPCC served as the core tenets of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The Executive Summary of the Policymakers’ Summary of the Working Group I Report reads:

We are certain of the following: there is a natural greenhouse effect … emissions resulting from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases: CO2, methane, CFCs and nitrous oxide. These increases will enhance the greenhouse effect, resulting on average in an additional warming of the Earth’s surface. The main greenhouse gas, water vapor, will increase in response to global warming and further enhance it.

We calculate with confidence that: … CO2 has been responsible for over half the enhanced greenhouse effect; long-lived gases would require immediate reductions in emissions from human activities of over 60 percent to stabilize their concentrations at today’s levels …

Under the IPCC business as usual emissions scenario, an average rate of global mean sea level rise of about 6 cm per decade over the next century (with an uncertainty range of 3–10 cm per decade), mainly due to thermal expansion of the oceans and the melting of some land ice. The predicted rise is about 20 cm … by 2030, and 65 cm by the end of the next century.

(IPCC, 1990)

The UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), or Earth Summit, in 1992 was organized by Maurice Strong, who had also been the UN Secretary-General at the Stockholm Conference in 1972. This was probably the most important conference the UN has held on sustainable development.

The conference produced or incubated the most ‘hard law’ (legally binding agreements) of any UN conference. These were: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992); the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (1992); the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (1994); the Straddling Fish Stocks Agreement (1995); the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (1998); and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2001).

The Earth Summit also produced Agenda 21 – the UN Blueprint for the Twenty-first Century, the Rio Declaration – 27 Principles for Sustainable Development, forestry principles to guide more sustainable forestry, and the setup of the UN Commission on Sustainable Development which would monitor the implementation of these agreements.

Agenda 21 had forty chapters that dealt with environmental, social, economic and governance aspects of sustainable development. However, Agenda 21 did not contain a chapter on energy, since the United States and oil states had lobbied successfully for this not to be included. This critical omission would be reversed five years later when governments adopted a number of new chapters to Agenda 21 addressing transport, energy and tourism.

Importantly, Agenda 21 did include a chapter on water that itself built on the Dublin Principles that had been agreed the previous year. Through a preparatory process dedicated specifically to water, the principles have achieved enduring and widespread attention:

Principle 1: Fresh water is a finite and vulnerable resource, essential to sustain life, development and the environment.

Principle 2: Water development and management should be based on a participatory approach, involving users, planners and policy-makers at all levels.

Principle 3: Women play a central part in the provision, management and safeguarding of water.

Principle 4: Water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognized as an economic good.

(Dublin Principles, 1991)

The emphasis placed by the Dublin Principles on water having economic value was contested by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), who saw water primarily as a universal human right. This issue would be underlined by the World Water Forum in 2000 when the World Commission on Water for the 21st Century published its World Water Vision Commission Report, saying:

Pricing of water services at full cost. Making water available at low cost, or for free, does not provide the right incentive to users. Water services need to be priced at full cost for all users, covering all costs related to operation and maintenance for all uses and investment costs for at least domestic and industrial uses. The basic water requirement needs to be affordable to all, however, and pricing water services does not mean that governments give up targeted, transparent subsidies to the poor.

(World Water Commission, 2000)

This tension between water as an economic and as a social good would overshadow much of the water discussion until November 2002, when the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights adopted General Comment No. 15, formulated by experts and reading:

The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses. An adequate amount of safe water is necessary to prevent death from dehydration, to reduce the risk of water-related disease and to provide for consumption, cooking, personal and domestic hygienic requirements.

(UN, 2002a)

General Comment 15 recognizes water not only as a limited natural resource and a public good, but also as a human right. The Comment’s adoption was seen as a decisive step towards the recognition of water as a human right. However, it took until September 2010 and the Fifteenth Session of the UN Human Rights Council to pass a resolution reaffirming and refining an earlier General Assembly resolution (64/292). The refinements included the elimination of reference to international finance supports, which had prompted some, mainly industrialized nations to abstain from the earlier UNGA resolution.

the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights … the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living and inextricably related to the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as well as the right to life and human dignity.

In the area of Agriculture, Chapter 14 of Agenda 21 dealt with the idea of ‘Promoting Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development’ (SARD) for the first time in a UN document. It described the food challenge in stark terms:

By the year 2025, 83 per cent of the expected global population of 8.5 billion will be living in developing countries. Yet the capacity of available resources and technologies to satisfy the demands of this growing population for food and other agricultural commodities remains uncertain.

(UN, 1992)

Agenda 21 saw the development of SARD as a mechanism to address this challenge.