eBook - ePub

The Modernization of Inner Asia

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Modernization of Inner Asia

About this book

Inner Asia - in premodern times the little-known land of nomads and semi-nomads - has moved to the world's front page in the 20th century as the complex struggles for the future of Afghanistan, Soviet Central Asia, Tibet and other territories make clear. But because Inner Asia as a whole is divided among several states politically and among area specialists academically, broad perspectives on recent events are difficult to find. This work treats the region as a single unit, providing both an account of the region's past and an analysis of its present and its prospects in a thematic, rather than a strictly country-by-country manner.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Premodem Heritage (to the 1920s)

1

Introduction

In Part I (chapters 1–7) of this study we are concerned with the bearing of the premodem heritage of the societies of Inner Asia on their capacity to modernize in the twentieth century. More specifically, we are asking which aspects of the traditional heritage were assets to future change and which were liabilities. Which traditional structures were readily convertible to modem functions? Which requisites of modernity were so lacking in the heritage that adoption of foreign institutions rather than the adaptation of traditional ones proved to be necessary?

A framework for answering questions such as these, supplementing the brief introduction to problems of comparative modernization set forth in the opening pages (“The Problem: Inner Asia and Modernization”), may be drawn from the studies of modernization of Japan, Russia, China, and the Ottoman Empire, which are forerunners of this study of Inner Asia, as well as from the general literature on the subject. In effect, we are setting forth the characteristic attributes of relatively modernized societies, and seeking to determine the extent to which the institutions and values of selected premodem societies are adaptable to these modem functions.

Since later-modernizing societies of necessity confront the problems of societal transformation in a context of more advanced societies, the first set of questions we ask deals with their capacity to operate in this environment. Do the societies of Inner Asia have a sense of national identity adequate to sustain their cohesion in a period of domestic and international strife? Have they experienced a reasonable stability of population and integrity of territory and boundaries? Have their political systems developed a capacity for social engineering such as is involved in regulating systems of land tenure and administering communications and public works?

The ultimate test of a society with a firm sense of national identity and an effective political system is its capacity to defend itself against colonization. Such a capacity depends on the recognition of the need to adapt traditional institutions to new functions and to borrow from more advanced societies without significant loss of national identity. Although many societies meet the initial challenge of the scientific and technological revolution by borrowing advanced institutions for the purpose of defending the traditional system—Peter the Great borrowed foreign military technology, but strengthened serfdom—this is as likely to impede as to further later efforts at modernization.

A second set of questions concerns the political structure of a traditional society. Do the dominant interest groups accept the leading role of the central political authorities? Does service to the state have a high priority for traditional elites? Does the government have the capacity to mobilize and allocate skills and resources on a regional and national basis? What experience does the bureaucracy have in administering political structures extending from the national to the local level? Do mechanisms exist for communication between the central government and the variety of local and regional corporate interest groups that characterize most societies?

As regards the economy of premodem societies, one wishes to know whether the political system had the capacity to mobilize resources for central purposes, and to pursue economic policies favorable to growth. Did agriculture produce a surplus? Were raw material resources exploited? Were handicrafts and manufacturing at a level sufficient to provide a basis for the development of modem industry? Had a groundwork been laid in such services as communications and transportation, local and regional markets, and financial institutions that might be adapted to modem needs?

A fourth set of questions concerns the premodem level of social integration—the interdependence of individuals and organizations welding families, villages, and regions into a functioning society. More specifically, was a significant share of the population located in towns and cities? Was occupational stratification developed to provide skills for management, manufacturing, and administration? Had the demographic cycle evolved beyond the typical premodem pattern of high birth and high death rates? To what extent did administrative, religious, and economic organizations provide a bridge between the primary family and kinship loyalties and the larger society?

Finally, in the realm of knowledge and education, we wish to understand the nature of premodem world views—the traditional interpretations of the physical and human environment—and the problems faced by premodem societies in adapting to modem knowledge as it has evolved since the revolution in science and technology. Is the premodem society inward looking, in the sense that its culture assumes that it has the ultimate truths and that all other views are by definition heretical? Or is it outward looking as a result of experiences in borrowing from and interaction with other cultures before the modem era? How does a premodem society become acquainted with modem knowledge? To what extent and in what ways is the traditional culture a barrier to the acceptance of modem knowledge? What efforts are made to translate foreign books? Were the elites introduced to modem knowledge from within through a reform of native education, or from without by colonizers or by missionaries? Did the traditional culture include libraries and the publication of books and periodicals? Did they have schools for commoners, and what did these schools teach?

2

International Context

Introduction

All societies face in due course the challenge of adapting traditional institutions and values to modem functions, and the process normally involves a struggle within each society between traditional and modernizing leaders. The nature of this struggle depends to a very significant degree on the international context of a given society: whether policies of modernization are undertaken relatively early or relatively late as compared with other societies; whether the process of change is essentially domestic, or takes place predominantly under foreign influence; and whether the society has a heritage of territorial and cultural continuity providing a strong sense of identity, or was formed from diverse peoples and territories during the modem era.

England and France adapted their societies to the new functions made possible by the revolution in science and technology over a period of many decades and in the absence of more advanced foreign models. For them the process was a natural one, and in a sense unconscious, insofar as it was gradual and pragmatic and did not involve threats to national identity or security from more advanced societies. To a considerable extent the offshoots of the early-modernizing societies in the New World benefited from a similar absence of outside pressure.

For the later modernizers, however, the international context plays a vital role in the aims and methods of their leaders. At the very least, the later modernizers are under the pressure of the example provided by more modem societies, which can be easily observed. Individuals going to more advanced countries for specialized training return with images of the reforms needed in their own society. More often than not, the example of more modem societies is imposed by military defeat and colonialism. Under these circumstances, the adaptation of traditional institutions and values to modem functions is marked not only by the normal domestic conflict but also by a struggle for national liberation.

In such relatively developed countries as Germany and Italy, for example, problems of national unification slowed the pace of political, economic, and social change substantially. To a much greater extent in less developed societies, the formation of nations from tribes and ethnic groups, with no common historical experience apart from subjection to colonial rule, presents almost insuperable obstacles to the efforts of their leaders to formulate common policies.

The influence of the international context on the process of societal transformation is explored here in terms of three factors: (1) the extent to which a society has developed a sense of identity before the modem era; (2) the nature of the foreign influences to which a society is exposed; and (3) the ways in which a society meets the challenges of modernity.

The capacity of a society to meet the challenges of the modem world depends significantly on the existence of a society-wide sense of identity—the loyalty of individuals and groups to institutions and values that facilitate the pursuit of common policies. The extent to which leaders can command the loyalty and altruism of its citizens is based largely on this sense of identity. In most premodem societies, identity is primarily related to kinship, and to a lesser degree to villages, regions, and religious associations. The great majority of people do not see their personal security as significantly related to larger linguistic or ethnic affiliations. The creation of society-wide, or “national,” patterns of identity is a distinctly modem development, called for by the need to mobilize resources for a wide range of political, economic, and social undertakings.

Premodem societies vary considerably in the extent to which a significant degree of society-wide identity was developed before the modem era. In England and France, Japan and Russia, most citizens, even though they did not yet think of themselves as English, French, Japanese, or Russians, were aware of national institutions and society-wide languages that transcended their local customs and dialects. Even today significant localisms remain in these countries, but the heritage of common loyalties has been sufficient to provide a viable basis for the society-wide organizational efforts required by political development, economic growth, and social mobilization. Most countries have not had this degree of premodem social cohesion. There is no easy way to compare identity patterns, but one must do the best one can to evaluate the extent to which a society enters the modem world with a sense of loyalty and altruism that extends beyond the immediate local environment and kinship structures.

In all later-modernizing societies the struggle between traditional and modernizing leaders has taken place under the influence of foreign models. In the case of Inner Asia, and of most other parts of Asia and also Africa, the nature and degree of foreign influence were less the choice of political leaders than the result of the irresistible pressures of outside forces. Especially in the period of the imperial expansion of the European powers and the complementary assertion of Chinese influence in the nineteenth century, even the remote territories of Inner Asia became the object of imperial competition. The Great Game of British-Russian rivalry in Inner Asia is the best known of these competitions, but France, Italy, and Japan also played a role. In its declining years, Ch’ing China likewise extended its influence to the north and west even as it surrendered to European influence in the east.

The purpose of this imperial activity was security rather than modernization, but the intrusion of outside military forces and political influences inexorably impressed the subject peoples with the levels of achievement that enabled the outside powers to exert their influence. In seeking to resist foreign influence, local leaders sought to adopt some of their practices. At the very least, they sought foreign assistance in strengthening their military forces by introducing modem weapons and principles of organization. This often led to a form of defensive modernization, the reform of military and political institutions for the purpose of preserving the traditional culture. As contacts with the outside world became more frequent, however, this in turn led to a more profound understanding of the multiple challenges of the modem era and of the need for undertaking thoroughgoing modernization.

The process of modernization is also affected by the way in which a society meets the initial challenge of the scientific and technological revolution. The leaders of some societies become aware of the challenge before they are directly confronted with it They meet it by sending commissions to survey the institutions of more advanced countries, by establishing research and training institutions to translate and study foreign books, and by launching programs of defensive modernization designed to strengthen the state against foreign intrusion before they are ready to undertake a broader program of societal transformation. Japan and Russia, and to a lesser extent the Ottoman Empire, followed this pattern. In the case of most other societies, the traditional leaders failed to anticipate the necessity for modernizing reforms, and their countries underwent a prolonged period of turbulence as rival groups interacted with foreign influences in the search for appropriate policies.

In countries that were able to resist direct foreign intervention, either because they had developed reasonably effective central governments before the modern era, as in the case of Iran, or because they survived as a buffer zone between major powers, as in the case of Afghanistan and Outer Mongolia, native political leaders had the capacity to exercise considerable influence in deciding which foreign models seemed most suited to their needs. The societies that underwent one degree or another of colonial rule, more often than not because they lacked the capacity to resist foreign intrusion, came under more direct foreign influence and tended to adopt the institutions and sometimes even the languages of the colonial powers in their early efforts to modernize.

Identity Patterns

Despite many differences in historical experience, Iran and Afghanistan resemble each other in that they were composed of diverse tribal and ethnolinguistic

groups concerned primarily with local issues and lacking in a sense of what has come to be known as “national” identity. Although empires embracing these local entities rose and fell over the centuries, they had little influence on the predominance of locally centered identity patterns. Even the Islamic culture, shared by most of these peoples, was so fractured by sectarianism and ethnic diversity that it failed to provide a common basis for political action. The predominant concern of the peoples of these regions with local tribal and territorial conflicts was much too intense to be affected by the abstract precepts of a common religious heritage.

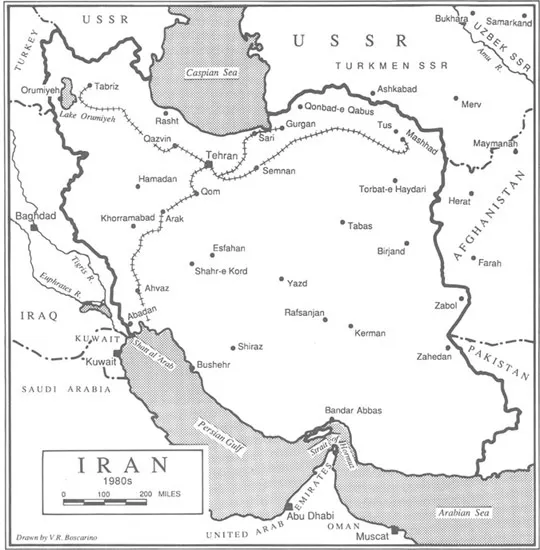

In the case of Iran (or Persia as it was known until 1935), the geographic distribution of ethnic groups has remained approximately the same since the Safavid period (1501–1736). Persian speakers dominate the central plateau and mountains and most of the eastern border with Afghanistan, while non-Persian speakers occupy the rimlands from Azerbaijan in the northwest down the Zagros

Mountains and along the Persian-Arabian Gulf coast. Using Azerbaijan again as a pivot, and moving to the east to the shore of the Caspian Sea and across the Elburz Mountains to Turkestan, other non-Persian ethnic groups are found. Persian is not only the administrative language, however, it is also the lingua franca for most of the country.

Imami Shi‘a Islam has been the state religion since the sixteenth century, and the instability of the royal inheritors led to an increase in the influence of the Shi‘a religious leaders. With few exceptions, they have retained at least residual political power. The dominant Shi‘a have also tended to persecute members of other Islamic sects, particularly Sunni, and also Zoroastrians (Parsees) and Bahais.

Afghan ethnolinguistic distribution has varied more widely from period to period than that of Iran. Mass shifting of dissident populations became the favorite outdoor sport of Afghan amirs in the nineteenth century, but reached a climax during the reign of Abdur Rahman (1880–1901). A Durrani Pushtun himself, Abdur Rahman first defeated rival Pushtun tribes (the population of modem Afghanistan is about one-half Pushtun) and then set about the conquest of non-Pushtun areas, a process of “internal imperialism.” The amir forcibly moved various dissident Pushtun groups to north Afghanistan and resettled them among non-Pushtun elements: Tajik, Uzbek, Turkmen, Hazara, Aimaq. To non-Pushtun “Afghans,” the term “Afghan” refers only to the Pushtun. This has proved to be a great barrier to the creation of a feeling of nationalism, a necessary corollary to modernization.

Hanafi Sunni Islam is the dominant sect in Afghanistan, with about one-fifth of the population Shi‘a, mainly Imami Shi‘a (Hazara) or Ismailiya (some Hazara, but mainly in parts of Badakhshan and Wakhan). Christian missionaries, partly successful in Persia, have never been permitted to proselytize openly in Afghanistan.

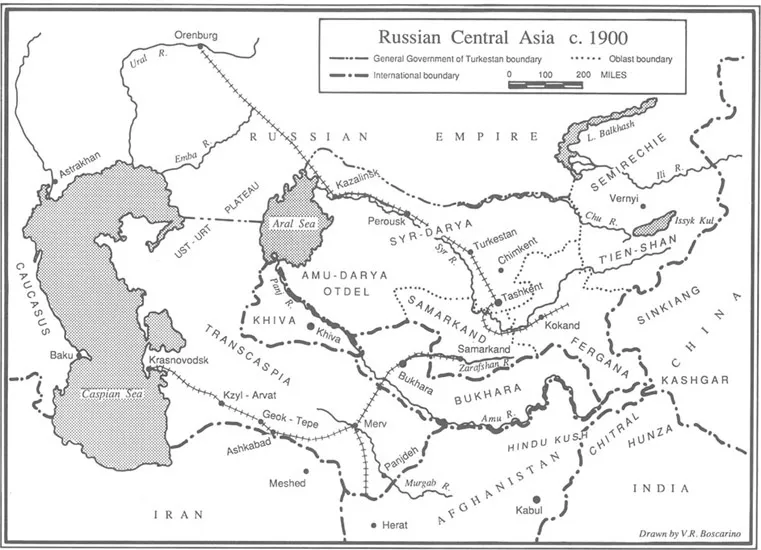

Russian Central Asia reflects a more complex pattern of ethnic and cultural interaction, dominated by the Turkic and Iranian populations who have inhabited the area for at least a millennium and a half. The Turkic peoples today by far outnumber the Iranian, but the Iranian population was initially both more numerous and administratively and culturally more significant. By the time of Cyrus the Great in the sixth century B.C., Iranian merchant groups and craftsmen had established a strong commercial and bureaucratic presence in the caravan cities and oases of Central Asia, adding a creative new element to the indigenous Soghdian, Khorezmian, and Baktrian peoples of the area. Their commercial, cultural, and administrative skills have been important in shaping the civilization of the area to this day. These have been essentially urban, settled groups whose influence on, and critical interaction with, the initially rougher and less polished Turkic nomadic peoples who migrated into the area later shaped the peculiarly symbiotic culture of the Inner Asian heartland.

The superior military power of the Turkic peoples allowed them to dominate the sedentary urban and oases complexes throughout these regions and gradually impose their political control over the Iranian peoples who inhabited the settled areas. It was the Turkic nomads who provided the ruling houses for the variousoasis states that emerged in this fashion, with the Iranian urban groups supplying the essential administrative and bureaucratic skills and services that made up the infrastructure of those political formations. These Turkic ruling dynasties would often establish a nominal residence in som...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- The Authors

- Preface

- The Problem: Inner Asia and Modernization

- Part I The Premodern Heritage (to the 1920s)

- Part II The Modern Era (1920s to 1980s)

- Part III Patterns and Prospects: Inner Asia and the World

- Comparative Chronology of Inner Asia

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Modernization of Inner Asia by Cyril E. Black,Louis Dupree,Elizabeth Endicott-West,Daniel C. Matuszewski,Eden Naby,Arthur N. Waldron in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 21st Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.