![]()

1

A Framework for Understanding Organizational Ethics

O.C. Ferrell

Organizational ethics is one of the most important, yet perhaps one of the most overlooked and misunderstood concepts in corporate America and schools of business. Organizational ethics initiatives have not been effectively implemented by many corporations, and there is still much debate concerning the usefulness of such initiatives in preventing ethical and legal misconduct. Simultaneously, business schools are attempting to teach courses and integrate organizational ethics into their curricula without general agreement about what should be taught or how it should be taught.

Societal norms require that businesses assume responsibility to ensure that ethical standards are properly implemented on a daily basis. Such a requirement is not without controversy. Some business leaders believe that personal moral development and character are all that is needed for effective organizational ethics. These business leaders are supported by certain business educators who believe that ethics initiatives should arise inherently from corporate culture and that hiring ethical employees will limit unethical behavior within the organization. A contrary position, and the one espoused here, is that effective organizational ethics can be achieved only when proactive leadership provides employees from diverse backgrounds with a common understanding of what is defined as ethical behavior through formal training, thus creating an ethical organizational climate. In addition, changes are needed in the regulatory system, in the organizational ethics initiatives of business schools, and in societal approaches to the development and implementation of organizational ethics in corporate America.

According to Richard L. Schmalensee, dean of the Sloan School of Management at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the question is, "How can we produce graduates who are more conscious of their potential ... and their obligation as professionals to make a positive contribution to society?" He states that business schools should be held partly responsible for a cadre of managers more focused on short-term gains to beat the market rather than on building lasting value for shareholders and society (Schmalensee 2003).

This introductory chapter provides an overview of the ethical decision-making process. It begins with a discussion of how ethical decisions are made in general and then offers a framework for understanding organizational ethics that is consistent with research, best practices, and regulatory developments. Using this framework, the chapter then discusses how ethical decisions are made in the context of an organization and poses some illustrative ethical issues that need to be addressed in organizational ethics.

Defining Organizational Ethics

Ethics has been termed the study and philosophy of human conduct, with an emphasis on the determination of right and wrong. For managers, ethics in the workplace refers to rules (standards, principles) governing the conduct of organization members. Most definitions of ethics relate rules to what is right or wrong in specific situations. For present purposes, and in simple terms, organizational ethics refers to generally accepted standards that guide behavior in business and other organizational contexts (LeClair, Ferrell, and Fraedrich 1998).1

One difference between an ordinary decision and an ethical one is that in an ethical decision accepted rules may not apply and the decision maker must weigh values in a situation that he or she may not have faced before. Another difference is the amount of emphasis placed on a person's values when making an ethical decision. Whether a specific behavior is judged right or wrong, ethical or unethical, is often determined by the mass media, interest groups, the legal system, and individuals' personal morals. While these groups are not necessarily "right," their judgments influence society's acceptance or rejection of an organization and its activities. Consequently, values and judgments play a critical role in ethical decision making, and society may institutionalize them through legislation and social sanctions or approval.

Individual versus Organization

Most people would agree that high ethical standards require both organizations and individuals to conform to sound moral principles. However, special factors must be considered when applying ethics to business organizations. First, to survive, businesses must obviously make a profit. Second, businesses must balance their desire for profits against the needs and desires of society. Maintaining this balance often requires compromises or tradeoffs. To address these unique aspects of organizational ethics, society has developed rules—both explicit (legal) and implicit—to guide owners, managers, and employees in their efforts to earn profits in ways that do not harm individuals or society as a whole. Addressing organizational ethics must acknowledge its existence in a complex system that includes many stakeholders that cooperate, provide resources, often demand changes to encourage or discourage certain ethical conduct, and frequently question the balancing of business and social interests. Unfortunately, the ethical standards learned at home, in school, through religion, and in the community are not always adequate preparation for ethical pressures found in the workplace.

Organizational practices and policies often create pressures, opportunities, and incentives that may sway employees to make unethical decisions. We have all seen news articles describing some decent, hardworking family person who engaged in illegal or unethical activities. The Wall Street Journal (Pullman 2003) reported that Betty Vinson, a midlevel accountant for WorldCom Inc., was asked by her superiors to make false accounting entries. Vinson balked a number of times but then caved in to management and made illegal entries to bolster WorldCom's profits. At the end of eighteen months she had helped falsify at least $3.7 billion in profits. When an employee's livelihood is on the line, it is difficult to say no to a powerful boss. At the time this chapter was written, Vinson was awaiting sentencing on conspiracy and securities fraud and preparing her twelve-year-old daughter for the possibility that she will be incarcerated.

Importance of Understanding Organizational Ethics

Understanding organizational ethics is important in developing ethical leadership. An individual's personal values and moral philosophies are but one factor in decision-making processes involving potential legal and ethical problems. True, moral rules can be related to a variety of situations in life, and some people do not distinguish everyday ethical issues from those that occur on the job. Of concern, however, is the application of rules in a work environment.

Just being a good person and, in your own view, having sound personal ethics may not be sufficient to handle the ethical issues that arise in the workplace. It is important to recognize the relationship between legal and ethical decisions. While abstract virtues such as honesty, fairness, and openness are often assumed to be self-evident and accepted by all employees, a high level of personal, moral development may not prevent an individual from violating the law in an organizational context, where even experienced lawyers debate the exact meaning of the law. Some organizational ethics perspectives assume that ethics training is for people who have unacceptable personal moral development, but that is not necessarily the case. Because organizations consist of diverse individuals whose personal values should be respected, agreement regarding workplace ethics is as vital as other managerial decisions. For example, would an organization expect to achieve its strategic mission without communicating the mission to employees? Would a firm expect to implement a customer relationship management system without educating every employee on his or her role in the system? Workplace ethics needs to be treated similarly—with clear expectations as to what constitutes legal and ethical conduct.

Employees with only limited work experience sometimes find themselves making decisions about product quality, advertising, pricing, hiring practices, and pollution control. The values that they bring to the organization may not provide specific guidelines for these complex decisions, especially when the realities of work objectives, group decision making, and legal issues come into play. Many ethics decisions are close calls. Years of experience in a particular industry may be required to know what is acceptable and what is not acceptable.

Even experienced managers need formal training about workplace ethics to help them identify legal and ethical issues. Changing regulatory requirements and ethical concerns, such as workplace privacy issues, make the ethical decision-making process very dynamic. With the establishment of values and training, a manager will be in a better position to assist employees and provide ethical leadership.

Understanding Ethical Decision Making

It is helpful to consider the question of why and how people make ethical decisions. Typically it is assumed that people make difficult decisions within an organization in the same way they resolve difficult issues in their personal lives. Within the context of organizations, however, few managers or employees have the freedom to decide ethical issues independently of workplace pressures. Philosophers, social scientists, and various academics have attempted to explain the ethical decision-making process in organizations by examining pressures such as the influence of coworkers and organizational culture, and individual-level factors such as personal moral philosophy.

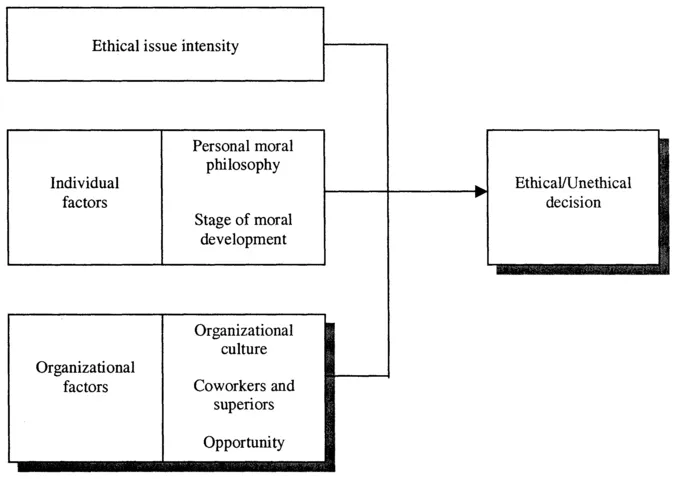

Figure 1.1 presents a model of decision making. This model synthesizes current knowledge of ethical decision making in the workplace within a framework that has strong support in the literature (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985; Ferrell, Gresham, and Fraedrich 1989; Hunt and Vitell 1986; Jones 1991; Trevino 1986). The model shows that the perceived intensity of ethical and legal issues, individual factors (e.g., moral development and personal moral philosophy), and organizational factors (e.g., organizational culture and coworkers) collectively influence whether a person will make an unethical decision at work. While it is impossible to describe precisely how or why an individual or work group might make such a decision, it is possible to generalize about average or typical behavior patterns within organizations. Each of the model's components is briefly described below; note that the model is practical because it describes the elements of the decision-making process over which organizations have some control.

Figure 1.1 A Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in the Workplace

Ethical Issue Intensity

One of the first factors to influence the decision-making process is how important or relevant a decision maker perceives an issue to be—that is, the intensity of the issue (Jones 1991). The intensity of a particular issue is likely to vary over time and among individuals and is influenced by the values, beliefs, needs, and perceptions of the decision maker, the special characteristics of the situation, and the personal pressures weighing on the decision. All of the factors explored in this chapter, including personal moral development and philosophy, organizational culture, and coworkers, determine why different people perceive issues with varying intensity (Robin, Reidenbach, and Forrest 1996). Unless individuals in an organization share some common concerns about specific ethical issues, the stage is set for conflict. Ethical issue intensity, which reflects the sensitivity of the individual, work group, or organization, triggers the ethical decision-making process.

Management can influence ethical issue intensity through rewards and punishments, codes of conduct, and organizational values. In other words, managers can affect the perceived importance of ethical issues through positive and negative incentives (Robin, Reidenbach, and Forrest 1996). If management fails to identify and educate employees about problem areas, these issues may not reach the critical awareness level of some employees. New employees who lack experience in a particular industry, for example, may have trouble identifying both ethical and legal issues. Employees therefore need to be trained as to how the organization wants specific ethical issues handled. Identifying ethical issues that employees might encounter is a significant step in developing employees' ability to make decisions that enhance organizational ethics.

New federal regulations that hold both organizations and their employees responsible for misconduct require organizations to assess areas of ethical and legal risk. Based on both the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the United States Sentencing Commission guidelines, these strong directives encourage ethical leadership. If ethical leadership fails, especially in corporate governance, there are significant penalties. When organizations communicate to employees that certain issues are important, the intensity of the issues is elevated. The more employees appreciate the importance of an issue, the less likely they are to engage in questionable behavior associated with the issue. Therefore, ethical issue intensity should be considered a key factor in the decision-making process because there are many opportunities for an organization to influence and educate employees on the importance of high-risk issues.

Under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, boards of directors are required to provide oversight for all auditing activities and are responsible for developing ethical leadership. In addition, court decisions related to the Federal Sentencing Guidelines for Organizations hold board members responsible for the ethical and legal compliance programs of the firms they oversee. New rules and regulations associated with Sarbanes-Oxley require that boards include members who are knowledgeable and qualified to oversee accounting and other types of audits to ensure that these reports are accurate and include all information material to ethics issues, A board's financial audit committee is required to implement codes of ethics for top financial officers. Many of the codes relate to corporate governance, such as compensation, stock options, and conflicts of interest.

Individual Factors

One of the greatest challenges facing the study of organizational ethics involves the role of individuals and their values. Although most of us would like to place the primary responsibility for decisions with individuals, years of research point to the primacy of organizational factors in determining ethics at work (e.g., Ferrell and Gresham 1985). However, individual factors are obviously important in the evaluation and resolution of ethical issues. Two significant factors in workplace integrity are an individual's personal moral philosophy and stage of moral development.

Personal Moral Philosophy

Ethical conflict occurs when people encounter situations that they cannot easily control or resolve. In such situations, people tend to base their decisions on their own principles of right or wrong and act accordingly in their daily lives. Moral philosophies—the principles or rules that individuals use to decide what is right or wrong—are often cited to justify decisions or explain behavior. People learn these principles and rules through socialization by family members, social groups, religion, and formal education.

There is no universal agreement on the correct moral philosophy to use in resolving ethical and legal issues in the workplace. Moreover, research suggests that employees may apply different moral philosophies in different decision situations (Fraedrich and Ferrell 1992); and, depending on the situation, people may even change their value structure or moral philosophy when making decisions. Individuals make decisions under pressure and may later feel their decisions were less than acceptable, but they may not be able to change the consequences of their decisions.

Stage of Moral Development

One reason people may change their moral philosophy has been proposed by Lawrence Kohlberg, who suggested that people progress through stages in their development of moral reasoning. Kohlberg contended that different people make different decisions when confronted with similar ethical situations because they are at different stages of what he termed cognitive moral development (Kohlberg 1969). He believed that people progress through the following three stages:

- The preconventional stage of moral development, in which individuals focus on their own needs and desires;

- The conventional stage of moral development, in which individuals focus on group-centered values and conforming to expectations;

- The principled stage of moral development, in which individuals are concerned with upholding the basic rights, values, and rules of society.

Obviously there is some overlap among these stages, so cognitive moral development should probably be viewed as a continuum rather than a series of discrete stages. Although Kohlberg did not specifically apply his theory of cognitive moral development to organizations, its application helps in explaining how...