eBook - ePub

Recession Prevention Handbook

Eleven Case Studies 1948-2007

Norman Frumkin

This is a test

Share book

- 379 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Recession Prevention Handbook

Eleven Case Studies 1948-2007

Norman Frumkin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book analyzes the performance of the economy and the economic policy actions of the Federal Reserve, the president, and the Congress in the twelve months preceding each of the eleven recession the United States has endured since the end of World War II. Incoroporating extensive real-time data, the book offers policy recommendations for preventing future recessions or at least limiting their impact.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Recession Prevention Handbook an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Recession Prevention Handbook by Norman Frumkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Characteristics of Recessions

This chapter discusses several general aspects of recessions in order to provide a broad underpinning for the essence of the book. The topics are:

• Business cycles and recessions

• Frequency of recessions since the early 1980s

• Severity of recessions

• Jobless recoveries from recent recessions

• Failure to forecast recessions and its policy implications

Business Cycles and Recessions

Business cycles are the recurring expansion and contraction of overall economic activity associated with changes in employment, income, prices, sales and profits. These cycles do not necessarily follow a standard pattern and they do not occur on a regular basis. In the United States, the time between recessions has typically varied from a few years (though in one case back-to-back recessions occurred only one year apart) to as much as a decade.

Each cycle has its unique characteristics that reflect the underlying structure of an economy, including the composition of industries and employment, inflationary pressures, private and public finance and the economy’s openness to domestic and international competition.

Business cycles occur predominantly in market economics, and they are especially prevalent in industrialized countries with highly developed business and financial infrastructures.

The nature of the business cycle can be affected by the appearance of new and substitute products, the introduction of new technologies, uncertainty and risk associated with business investment, stock market and real estate speculation, intensification of domestic and international competition, supply and price shocks due to cartels, disruptions in output and sharp increases in demand for products as a result of wars and other threats to national security. Businesses also face the ongoing challenge of accurately gauging the demand for their products in order to avoid shortages or inventory build-ups. Overshooting in either direction can contribute to business cycle swings.

Animal Spirits and Irrational Behavior

Also, it is important to keep in mind that households and businesses do not always act rationally. George Akerlof and Robert Shiller cite such lack of rationality as a major source of business recessions and depressions. “To understand how economics work and how we can manage them, we must pay attention to the thought patterns that animate people’s ideas and feelings, their animal spirits.”1

The idea of animal spirits in driving the macroeconomy originated with John Maynard Keynes in his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes defined animal spirits as a motivating force in initiating investments in which the potential returns are too problematic to be calculated realistically by an assessment of prospective costs and benefits. “Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be undertaken as a result of animal spirits—of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities. Enterprise only pretends to itself to be mainly actuated by the statements in its own prospectus, however candid and sincere. Only a little more than an expedition to the South Pole, is it based on an exact calculation of benefits to come.”2

Akerlof and Shiller note that irrational economic and noneconomic behavior is part of animal spirits that affect the overall economy. The intertwining of economic and noneconomic behavior consists of the degree of confidence that people have in the future, the aspect of fairness in setting prices and wages, corruption and bad faith present in economic enterprises, money illusion in focusing on the dollar value of income and assets while neglecting the effects of inflation on the purchasing power of income and assets, and stories that affect public perceptions received from the media, discussions with friends and fellow workers, and memories of past events, accurate and inaccurate. Moreover, Akerlof and Shilling consider that irrational behavior especially during prosperous times increases the risk of subsequent business recessions and depressions.

I have put forward the following examples of such irrational behavior in this book, I conclude that these behaviors were important factors leading to several recessions:

• Recessions of 1973–75, 1980, and 1981–82: The expectation of businesses and workers during the 1970s that high rates of inflation would continue indefinitely. This led them to engage in an upward spiral of prices and wages, with higher prices followed by demands for higher wages, higher wages followed by higher prices, and so on. Both sets of actions were undertaken to maintain business profit margins and the purchasing power of wages.

• Recession of 2001: The dot-com and stock market speculation in the last part of the 1990s in which the creation of telecommunications companies that often were not economically viable, or that existed on paper only. Much of the financing of the dot-com companies was fueled by a speculative rise in stock market prices. The general rise in stock market prices in turn hinged on expected growth of company profits and dividends so far into the future that it gave an overly optimistic view of company prospects.

• Recession of 2007–9: The perception by households, businesses, banks, and other lenders in the early 2000s that house prices would rise indefinitely. This mindset led households to buy houses priced much above what they could afford, and banks and other lenders to lower their lending standards much below prudent financial practice.

This concept of irrational behavior breaks with the classical economic theory of the “invisible hand” derived from Adam Smith, which assumes that the market is inherently efficient, and so results in only minimal shortterm deviations from long-term economic growth. In this view, the market contains a built-in self-correcting mechanism that smooths the short-term deviations from long-term growth into a residual of only minor recessions of short duration.

An earlier break with the premise of the invisible hand was of course John Maynard Keynes’ book noted above. The break was one of the components underlying Keynesian economics of using fiscal policy to stimulate economic growth when the economy is operating below its potential, and similarly, using fiscal policy to restrain economic activity when the economy is operating above its potential.

The irrational behavior associated with bringing on the several recessions cited above is driven by two general factors. One is the quality of the information that individuals and businesses possess, which ranges from accurate to inaccurate and complete to incomplete. This imperfect information diverges from the premise of efficient markets underlying the idea of the invisible hand, which assumes that all buyers and sellers have accurate and complete information.

The other is that individuals and businesses have varying psychological predilections for risk-taking, ranging from cautious to gambling. These innate predilections are also likely affected during particular periods by a herd mentality in which the thought is that, say, because prices of houses or stocks appear to be rising indefinitely into the future, houses and stocks will only become more expensive if not purchased at the present time. Other examples of differing predilections for risk-taking are the ranges of willingness to invest in new ventures, housing, and financial assets; to borrow funds for purchasing household goods, health, education travel services, etc.; to enlarge business operations, and for lenders to extend credit.

The varying quality of information that individuals and businesses possess on the one hand, and their varying psychological predilections for risk-taking on the other, may contribute to some irrational economic behavior on their part.

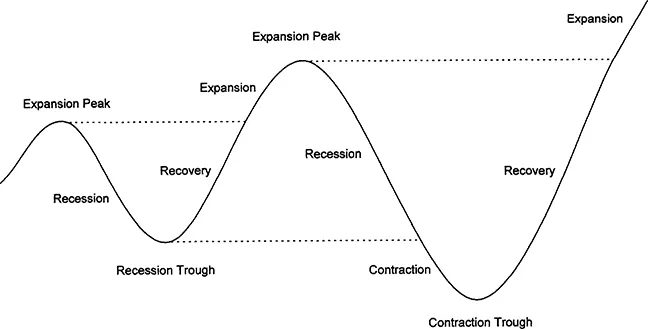

Business Cycle Phases

In most cases, a business cycle is composed of three stages: expansion, recession, and recovery; in rare cases, a fourth stage occurs, which I refer to as contraction.3 The four stages are defined as follows: Expansion and recovery refer to rising phases of a business cycle. A recovery has begun when the economy stops declining and turns upward. An expansion occurs when the upward recovery exceeds the level of the previous expansion. Recession and contraction refer to falling phases of a business cycle. If, from the high point of an expansion, the economy turns downward with persistent declines in production and employment and increases in unemployment, then a recession has set in. In rare cases, when the decline in production and employment falls below the low point of the previous recession, a contraction has set in. The last contraction extended the 1981–82 recession. The high point of an expansion is referred to as the “peak,” and the low point of a recession/contraction is referred to as the “trough.”

Figure 1.1 depicts these generic phases of the business cycle.

It is important to note that a recession signifies an actual decline in production and employment. By contrast, a recession is not present when there is a decline solely in the rate of growth of production during an expansion (what mathematicians call a “second derivative”). This is referred to as a growth recession.

A last term that fortunately has not arisen since the 1930s is “depression.” A depression is a collapse of the economy affecting people in all social and economic strata, with mass unemployment, the widespread loss of assets such as homes and life savings, the disappearance of businesses through bankruptcy, and the undermining of the financial system through failures of the banking, securities, and insurance industries. A depression is far more devastating than a recession.4 For example, unemployment rose to about 25 percent in the Depression of the 1930s, compared with unemployment highs of 9 percent to 11 percent in the severe recessions of 1973–75, 1981–82, and 2007–9 and their subsequent recoveries.

There is no systematic formula or model that determines the onset or the end of a recession/contraction. The Business Cycle Dating Committee, convened by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. (NBER), a private nonprofit organization in Cambridge, Massachusetts, determines the designation of such cyclical turning points by its judgmental assessment of the movements of statistical measures of the economy, referred to as economic indicators. Examples of the economic indicators included in the cyclical assessment are business sales, bank debits outside New York City, industrial production, unemployment rate, nonfarm employment and hours worked, personal income, and the less cyclically sensitive gross domestic product (GDP) in nominal dollars and in inflationadjusted dollars (real GDP). Though statistical tests are applied to these and other economic indicators to assess their direction, ultimately the designation of the beginning and end of a recession/contraction is based on professional judgment. While the cyclical turning points are linked to a particular month, rather than to a quarter of the year, reference to the quarterly GDP data adds confidence in assessing the approximate time of the directional change.

Figure 1.1 Illustrative Phases of Business Cycles

However, the common implication by reporters, journalists, and politicians that a recession is determined when the real GDP declines for two consecutive quarters, is wrong. The behavior of the above-noted array of monthly indicators used by the Dating Committee determines, in the judgment of the committee, the particular month in which a recession begins and ends. The monthly indicators are used in the statistical preparation of the quarterly GDP, and the GDP measure of the overall economy is built up from the database of the monthly indicators as well as from a host of other statistical data. Therefore, the quarterly GDP is not nearly as sensitive or as timed to the cyclical movements of the economy as are the separate monthly indicators.

While the Dating Committee includes the GDP in its deliberations, it does not specify that a period of ec...