eBook - ePub

How Healthcare Data Privacy Is Almost Dead ... and What Can Be Done to Revive It!

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How Healthcare Data Privacy Is Almost Dead ... and What Can Be Done to Revive It!

About this book

The healthcare industry is under privacy attack. The book discusses the issues from the healthcare organization and individual perspectives. Someone hacking into a medical device and changing it is life-threatening. Personal information is available on the black market. And there are increased medical costs, erroneous medical record data that could lead to wrong diagnoses, insurance companies or the government data-mining healthcare information to formulate a medical 'FICO' score that could lead to increased insurance costs or restrictions of insurance. Experts discuss these issues and provide solutions and recommendations so that we can change course before a Healthcare Armageddon occurs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How Healthcare Data Privacy Is Almost Dead ... and What Can Be Done to Revive It! by John J. Trinckes, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Service Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

CODE BLUE

Privacy is not about whether or not you have something to hide. It’s about having the right to choose what you want to keep to yourself—and what you want to share with others.

—Aral Balkan (Balkan, 2016)

Erroneous Information

It was another beautiful day in Florida as Dr. Smith, a new physician intern, was preparing his rounds. Dr. Smith logged onto his computer and pulled up the record of his first patient in his hospital’s electronic medical record software. Going through the patient’s notes, he noted that the patient was a “status post BKA (below the knee amputation).” He read through other parts of the record to get a good understanding and medical background of his patient. Being a new doctor, Dr. Smith took special care in knowing his patients. He also tried very hard to impress his attending physician, Dr. Jones. Dr. Smith had already figured out a diagnosis for the symptoms his patient was complaining about as Dr. Jones met him at the patient’s door.

Dr. Jones is an “old school” doctor and doesn’t necessarily care for the new records’ technology. He would rather talk to the patient to get to know them first as opposed to relying solely on the data in the electronic medical record.

“Good morning, Dr. Jones,” Dr. Smith called out as he continued to type away on the computer.

“Good morning, Dr. Smith. Who do we have to see this morning?”

“This is Mr. Ford. He is complaining of flu-like symptoms and he is also a status post BKA,” Dr. Smith responded.

The senior attending physician, Dr. Jones, asked, “Oh, how do you know he is status post BKA?”

Looking up from his keyboard, Dr. Smith explained, “Mr. Ford’s several past discharge notes all indicated this status, and based on the symptoms he is currently presenting, I think I know his diagnosis.”

“Okay,” Dr. Jones replied, “let’s go check the patient out.”

As the doctors entered the room, they found the patient up on the exam bed with two perfectly working feet. With a surprise, Dr. Smith questioned, “How is this possible?”

Dr. Jones responded with a sigh, “Technology.”

*****

Although the names in this story are fictional, the story was based on true events. As it turned out, the patient was seen in the hospital many times and on a prior visit, the voice recognition dictation system used to assist physicians with entering their notes into the electronic medical record solution misunderstood DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis) as “B”KA. The physicians that reviewed the medical record before didn’t catch the error and it had become a permanent part of the patient’s record (Hsleh, 2016).

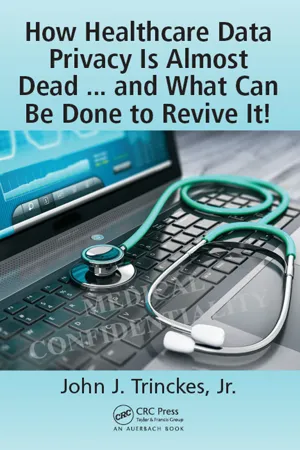

No harm came to the patient and the error was easily fixed, but what about the horror stories we hear on the news of surgery mishaps where wrong organs or body parts are removed from patients? “Over a period of 6.5 years, doctors in Colorado alone operated on the wrong patient at least 25 times and on the wrong part of the body in another 107 patients, according to the study, which appears in the Archives of Surgery” (Gardner, 2016). When new physicians are only spending about eight (8) minutes of their time with patients, while in contrast they spend 40% of their time utilizing the information systems, one may see why we hear about stories of patients dying from allergic reactions to drugs that were incorrectly reported in their medical records. Or how about people being wrongly diagnosed? (Figure 1.1).

In 2004, Trisha Torrey, now a patient advocate, was diagnosed with an “aggressive, deadly cancer, and six months to live unless I got the necessary chemo to buy myself an extra year” (Share Your Story—Medical Errors, 2016). Trisha took it upon herself to learn all she could about the diagnosis and the lab results that led up to it. After learning more and deciphering some of the results, Trisha was convinced she didn’t have cancer, but the battle was on to prove it. After fighting a system that didn’t want to admit that they were wrong, the final word came down upon a review of an expert from the National Institute of Health that finally put the issue to rest. Years later, Trisha never had a treatment and now speaks, performs broadcasting activities, and writes for About.com and Every Patient’s Advocate (http://trishatorrey.com) to improve patients’ outcomes.

Figure 1.1 Comparison of hospital interns’ time spent with patients versus interaction with information systems. (From Gunderman, R., The drawbacks of data-driven medicine, Retrieved from The Atlantic, http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/06/the-drawbacks-of-data-driven-medicine/276558/, May 29, 2016.)

A study “from doctors at Johns Hopkins, suggests medical errors may kill more people than lower respiratory diseases like emphysema and bronchitis do” (Christensen, 2016). If this is true, medical mistakes would be just behind heart disease and cancer as the third leading cause of death in the United States. Estimates indicate “there are at least 251,454 deaths due to medical errors annually in the United States” (Christensen, 2016). Most of these errors can be contributed by human or technology errors related to miscom-munications substantiating the fact that we have a serious issue on our hands.

Not only can errors be propagated through an individual’s own medical record, but with the number of individuals seeking healthcare services, we need to be concerned with records being mixed up. In another case, two individuals with the same first and last name were seen in a provider’s office at the same time. Confusion occurred and procedures were performed on the wrong patient. According to Chief Executive Officer Lynn Thomas Gordon of the American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA), “Accurately matching the right information with the right patient is crucial to reducing potential patient safety risks. At the very foundation of patient care is the ability to accurately match a patient with his or her health information” (Davis, 2016a). In a survey conducted on eight hundred fifteen (815) AHIMA members using a dozen different electronic medical record solutions, less than half indicated they had a quality assurance process in place during or after the registration process to ensure patients are matched to their appropriate records along with minimizing or correcting duplicate records.

The survey indicated that fifty-five percent (55%) of the respondents had policies related to duplicate records, but no standards on how these duplication rates factored into their organization. Only forty-three percent (43%) indicated they utilize patient matching in metrics to measure data quality. The survey authors state, “Reliable and accurate calculation of the duplicate rate is foundational to developing trusted data, reducing potential patient safety risks and measuring return on investments for strategic healthcare initiatives” (Davis, 2016a).

Of course patient safety is the top concern for matching the appropriate medical records to the right patient, but it is also a financial burden. Marc Probst, the chief information officer for Intermountain Health, a healthcare system based in Utah, indicated his organization spends $4-$5 million annually on costs associated with administration and technology related to accurately matching records. Probst states, “As we digitize healthcare and patients move from one care setting to another, we need to ensure with 100 percent accuracy that we identify the right patient at the right time. Anything less than that increases the risk of a medical error and can add unnecessary costs to the healthcare system” (McGee, 2016a).

It sort of makes sense that we should have a primary “key” or identifier that could be utilized to ensure all medical records associated to you are accurately matched back to you, right? Why didn’t anyone think about this before? Well, Congress did and called for the creation of a unique health identifier for individuals when it passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. In response to privacy concerns, however, three years later, Congress prohibited the funding of this identifier.

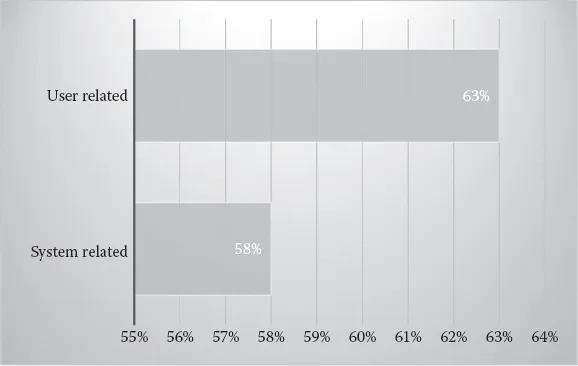

Unfortunately, the failure to match records accurately and without a standard employed across the entire healthcare system has led to patient safety and privacy concerns. Accordingly to a RAND Corporation study, “providers on average incorrectly match records and patients about 8% of the time, costing the U.S. health care system about $8 billion annually” (The Advisory Board Company, 2016). Issues range from minor inconveniencies to all-out fatal results. A report published in the Journal of Patient Safety titled Electronic Health Record-Related Events in Medical Malpractice Claims provided a plethora of case examples where someone was harmed due to a related electronic medical record error and a lawsuit occurred. “Considerably over 80% of the reported errors involve horrific patient harm: many deaths, strikes, missed and significantly delayed cancer diagnoses, massive hemorrhage, 10-fold overdoses, ignored or lost critical lab results, etc.” (Koppel, 2016). As seen in Figure 1.2, users are more commonly to blame than systems; however, in some cases, there were multiple factors that led to harm. To be fair, most of these examples weren’t directly related to a matching error, but these do demonstrate the extent and complexities of the issues as the healthcare industry was so quickly forced to turn over to technologies that may not have been thoroughly vetted.

Figure 1.2 System-related versus user-related issues (total of 248 cases). (From Mark Graber, D.S., Electronic health record-related events in medical malpractice claims, Retrieved from Journal of Patient Safety, http://pdfs.journals.lww.com/journalpatientsafety/9000/00000/Electronic_Health_Record_Related_Events_in_Medical.99624.pdf?token=method|ExpireAbsolute;source|Journals;ttl|1463323186055;payload|mY8D3u1TCCsNvP5E421JYK6N6XICDamxByyYpaNzk7FKjTaa1Yz22MivkHZqjGP, May 15, 2016.)

For these reasons, organizations are calling for Congress to assist in the implementation of a national patient identifier and why the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives (CHIME) has launched a $1 million competition with HeroX, a crowdsourcing site, to encourage innovators in developing a national patient identifier solution. According to CHIME’s CEO Russell Branzell, the identification system “could be a number, a complex software/algorithmic system, it could be biometric, using handprints or some other characteristic” (The Advisory Board Company, 2016).

This may sound like an easy task, but it is much more involved than one would think. Since there is no current standard in place for entering individuals’ names or other demographic information, it becomes very difficult to ensure that individuals are appropriately identified. Most providers use algorithms that employ several pieces of personal information like a Social Security number, date of birth, and name to match these records. What happens if a name is spelled wrong or a number is mistyped in a record? How does this record get matched to the appropriate individual? This task becomes even more difficult when privacy and security concerns must be considered and built into the solution from the start. Some would argue that it makes the healthcare system more private since “a key step to securing private information is determining whom it belongs to” (The Advisory Board Company, 2016). Others believe that the issue with privacy really involves the lack of regulations over data brokers and not patient identification itself. The $1 million prize is planned to be awarded in February 2017 to an individual, group, or organization that can develop a working prototype.

Medical Identity Theft

Being an older gentleman, Mr. Johnson was in great health. It had been a windy fall and leaves were collecting in his rain gutters. It was a sunny Monday morning and Mr. Johnson felt the urge to clean out these gutters before the winter snow set in. Mr. Johnson secured his ladder to the roof and began the tedious task of removing the leaves. After an hour or two, Mr. Johnson’s back started to hurt. Pain shot up from the middle of his back up through his arms. It got so bad that he had to stop cleaning and drive himself to the emergency room.

Dr. Clarke, the attending physician, walked into the exam room and said, “Good afternoon, Mr. Johnson. What brings you into the emergency room?”

“I was cleaning out my rain gutters and must have pulled something in my back. I’ve got a lot of pain that radiates into my arm,” Mr. Johnson explained, holding tears back in his eyes.

“Let’s order you an x-ray and see what we can find,” responded Dr. Clarke.

The x-ray results came back and nothing was broken. “It appears you have a muscle sprain. I’m also a little concerned with your temperature; it is a little high. It looks like you may also have a mild infection. I’m going to prescribe a muscle relaxer for your pain and it looks like we’ve given you penicillin before when you came here last time,” Dr. Clarke stated.

Mr. Johnson looked confused, “Last time? I’ve never been here before in my life! AND I’m allergic to penicillin. What are you trying to do doc, kill me?”

Come to find out, someone utilized Mr. Johnson’s insurance card, after he had previously lost it and the insurance company replaced it with the same number, to obtain medication and other services at the hospital. Although the names and events were changed, this story was based on actual events (Shin, 2016).

In another example, Katrina Brooke was enjoying the time with her new baby boy when three weeks after having him, she received a bill from a local health clinic addressed to her baby. The bill was for a prescription painkiller related to a back injury. After calling the clinic, it was confirmed that someone used her baby’s personal information to obtain services only a week after the baby was born. The clinic agreed to waive the charges (Rys, 2016).

In this case, it was easy to resolve the situation, but for other victims of medical identity theft it is more difficult. Anndorie Sachs, a mother of four, received a call from a social worker notifying her that her newborn tested positive to methamphetamines. The social worker notified Sachs her children were going to be taken into protective custody. Sachs hadn’t given birth in more than two years, but did lose her driver’s license that was utilized by Dorothy Bell Moran. Moran was on drugs and used Sachs’s name to give birth to a newborn. Sachs was able to keep her kids after several calls and hired an attorney to assist in recovering from any damages caused by the theft of her identity.

Sachs thought her problems were solved, but months later after being seen for a kidney infection, even though she avoided going to the hospital where Moran gave birth, Sachs found errors in her medical record. Her emergency contact and blood type were wrong. Sachs notified the staff and the error was immediately corrected, but with a blood-clotting disorder, a mistake in any medication given could have been deadly (Rys, 2016).

In another example, a psychiatrist, in order to gain more money from submitting false claims, entered false diagnoses into medical records for different disorders such as drug addiction and depression. The issue was finally caught, but not before a victim discovered the false diagnosis when he applied for a job (U.S. v. Skodnek, 933 F.Supp. 1108; 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 9788 [D. Mass. 1996]).

Medical identity theft can occur by multiple suspects for several different purposes. Family members who know personal information of their relatives may utilize this information to obtain costly medical services when they may not have insurance. Drug addicts or dealers could obtain prescription drugs by utilizing identities of individuals with insurance. Insiders...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- AUTHOR

- CONTRIBUTING AUTHOR

- CHAPTER 1 CODE BLUE

- CHAPTER 2 PRIVACY CONCERNS

- CHAPTER 3 HEALTHCARE ARMAGEDDON

- CHAPTER 4 VICTIMS

- CHAPTER 5 HEALTHCARE SECURITY

- CHAPTER 6 ENFORCEMENT

- CHAPTER 7 PRIVACY…CLEAR…<SHOCK>

- CHAPTER 8 SUMMARY

- REFERENCES

- INDEX