LARRY K. BRENDTRO AND ARLIN E. NESS

This civilization of vast intellectual, economic, and military power is at the same time weak and ineffectual at the basic human task of socializing children. One might presume that we would have created environments that guide all of our young toward responsible adulthood and nourish those with special needs. But large numbers of disturbed, delinquent, abused, and alienated youngsters populate our schools, community agencies, and children’s institutions. Typically our efforts to meet their needs are shamefully inadequate, suggesting that we do not know enough or care enough about serving such children. This book seeks to address these tandem issues of knowledge and concern, which are essential to creating powerful environments for redirecting young lives.

early approaches: pygmalion pioneers

Early leaders in youth work radiated an optimism in sharp contrast to many contemporary approaches, which concentrate on abnormality or pathology. Challenging prevailing attitudes of futility and cynicism, they approached difficult children with a powerful Pygmalion-like optimism, frequently achieving astonishing results.

In nation after nation such people have come forth in times of great difficulty, committed to a positive vision of the strength and potential that lay untapped in troubled youth. Among these pioneers were:

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827), the Swiss educator, who gathered together homeless and unwanted children who were victims of the Napoleonic wars and founded a residential school at Stans based on a progressive, humane philosophy.

Itard (1775-1838), the French physician, who challenged the diagnosis of experts and worked to reclaim Victor, a primitive wolf-child who had wandered wild and naked in the woods since being abandoned with a slit throat early in his life.

Nineteenth-century American reformers such as Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe (1801-1876), who established services for all kinds of handicapped children in New England, and Dorthea Dix (1802 -1887), a Sunday School teacher for female prisoners who awakened the nation’s conscience to the atrocities experienced by the mentally ill, including children incarcerated in almshouses, barns, and stables.

Rudolph Steiner (1861-1925), the Austrian humanitarian – spiritualist, whose philosophy guided the creation of the world-wide Waldorf School movement which offered a rich environment to children with all manner of handicaps and problems.

Makarenko (1888-1939), a Russian teacher and social worker, who accepted the challenge of developing colonies to serve the besprizorniki, masses of roving children who terrorized Soviet cities following the Russian revolution of 1917.

Sir Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), the Bengali philosopher, a recipient of the Nobel Prize in literature, whose poetry of love reflected his own deep concern and work with children in his school in Santiniketan near Bolpur, India.

Janusz Korczak (1879-1942), a Polish educator, who championed the rights of the young in 20 books with titles including Children of the Street (1901), How to Love a Child (1920), and The Child’s Right to Respect (1929). For 30 years he directed the House of Children, a Jewish orphanage in Warsaw, until he became a martyr in a final act of love and respect as he declined a Nazi offer for personal freedom to accompany 200 of his children to the gas chamber at Treblinka (Kulawiec, 1974).

An outstanding pioneer in American youth work was Jane Addams (1909), who worked with Chicago youngsters at the beginning of the twentieth century. Unlike many of her day (or others who were to follow in the profession), Addams had an immensely positive and optimistic outlook. She interpreted the stealing, vandalism, aggression, defiance, and truancy of youth as the normal expression of boys in search of adventure. She recalled that coast-dwelling youth in early America could find this outlet in the mystery of ships and the thrill of going to sea. In an industrial society youth were compelled to invent their own excitement, and this was the cause of many behavioral problems.

One cannot help but note that many contemporary theories have an intellectual rather than an emotional quality to them when contrasted with the thinking of pioneer youth workers who wrote from immediate experience. In fact, very few theories about the treatment of troubled youth have been derived directly from experience. Instead, an attempt is usually made to apply an existing conceptual framework (such as psychoanalysis or behaviorism) to the treatment of troubled youth. Training curricula for professional youth workers typically emphasize content that an “expert” has mastered rather than material that practitioners themselves need to know. We have found that one of the simplest but most easily overlooked ways of determining what staff should be taught about managing troubled youth is to ask them. Perhaps this approach is seldom used because trainers are uncomfortable with the type of questions raised. It can be a humbling experience to test any theory against the wisdom and searching questions that one encounters among those who work on the front lines.

Current Strategies

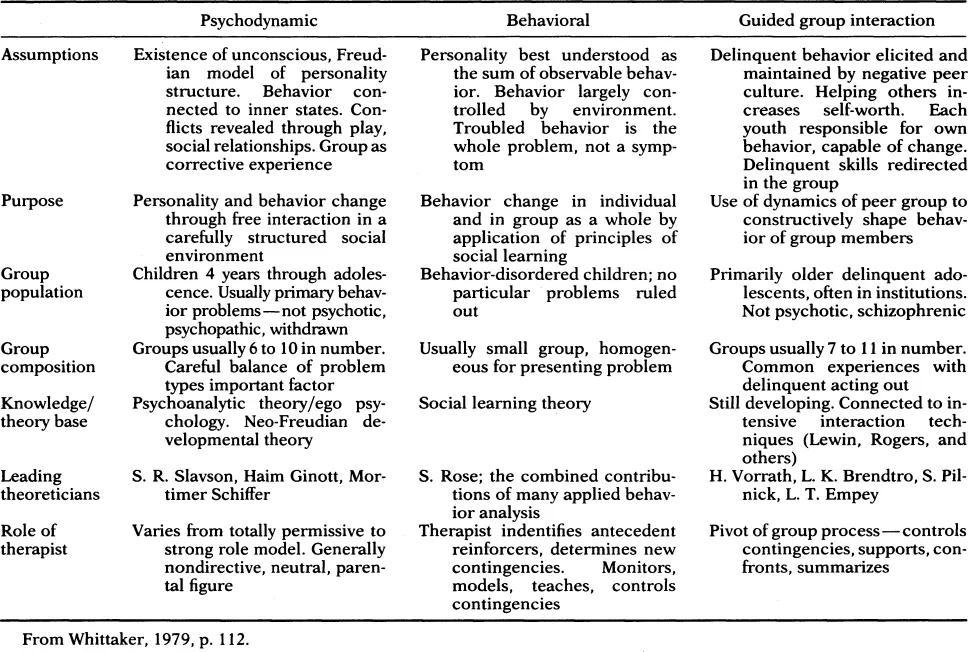

During the second half of the twentieth century, there has been a growing body of literature relating specifically to the treatment of troubled youth. Many of the early approaches emanated from the field of residential treatment rather than from public schools. Whittaker (1979) has identified three prominent schools of thought that have been developing in parallel in recent decades. The psychodynamic approach dominated the residential literature in the 1950’s beginning with the seminal contributions of Bruno Bettleheim (1950) at the University of Chicago Orthogenic School and Fritz Redl (Redl & Wine-man, 1951, 1952) at Pioneer House in Detroit. In the 1960’s the behavioral approach began to receive the greatest attention. A prominent example is the Achievement Place model, also known as the Teaching-Family model, developed by Phillips and his colleagues (1968, 1972). Simultaneously, guided group interaction strategies were also being widely employed with delinquents in correctional programs and were later extended to other types of youth and settings; this strategy first gained prominence with the work of McCorkle, Elias, and Bixby (1958) at Highfields in New Jersey. Whittaker (1979) provides a thorough discussion of these three approaches, which is summarized in Table 1-1.

Another residential model that has gained wide attention, particularly among special educators is the Re-ed concept of Hobbs (1967). Hobbs originated the Re-ed program as an American adaptation of the educateur common in Western Europe and Canada. The Re-ed Schools in Tennessee and North Carolina were developed in the early 1960’s as short-term 5-day residential treatment facilities serving small groups of disturbed students. Generic professionals called teacher-counselors worked in both the school and group living settings. Another key role was the liaison teacher, who provided a link with the child’s community ecology. Whittaker summarizes the core components of Hobbs’ approach as “developing trust, gaining competence, nurturing feelings, controlling symptoms, learning middle-class values, attaining cognitive control, developing community ties, providing physical experience, and knowing joy” (1979, pp. 73-74). The emphasis on teaching joy stems from the earlier work of the Russian youth worker Makarenko.

Because of a bias toward learning, it was perhaps inevitable that the Re-ed schools would gravitate toward the behavioral approaches that were achieving dominance during the same period. More recently, Hobbs has expressed some reservation about overemphasizing this component of the re-education experience. In a review of the first 20 years of project Re-ed, Hobbs states:

Our current view is that behavioral modification, powerful as it is, is not a sufficient theoretical base for helping disturbed children and adolescents. It pays insufficient attention to the evocative power of identification with an admired adult, to the rigorous demands of expectancy stated and implicit in situations, and to the fulfillment that comes from the exercise of competency (1979, p. 15).

With the development of the field of emotional disturbance as an area of special education, there has been a burgeoning of programs and theories. Rhodes and Tracy (1972) sought to organize these diverse concepts and identified six distinct models: psychodynamic, behavioral, sociological, biophysical, ecological, and counter-cultural.

Perhaps the broadest taxonomy of the various educational and residential remediation models for emotionally disturbed children is that of Kristen Juul (1980), who writes from an international perspective. Juul extends Rhodes’ categories to nine different models and notes that they are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Tracing the psychoeducational management of troubled children back approximately 200 years to Pestalozzi, he presents the nine models in the approximate historical sequence in which they emerged. He also emphasizes the contributions that two Austrians, Alfred Adler and August Aichorn, made to the field of therapeutic education. A summary of JuuPs taxonomy follows.

Table 1-1. Differential Approaches to Group Treatment of Children and Adolescents

1. The developmental model. In this view, the child’s emotional and social growth proceeds through predictable stages and sequences and results from the interaction of these stages with the child’s experiences. There are sensitive periods during which experiences and relationships are important or critical to the development of a healthy personality.

2. The psychodynamic model. This view stresses the importance of feelings and emotional needs in the belief that distorted interpersonal relationships lead to lasting personality disturbance. Treatment involves sensitizing significant people in the child’s life and responding to the child’s needs for relationships with mature and caring adults.

3. The learning disability model. Two major premises of this model are that (1) neurological dysfunctions directly hamper the child’s emotional and social functioning and (2) a child’s failure to learn in normal ways leads to feelings of inferiority and lowered self-esteem that may be related to other behavioral problems. Remediation usually takes the form of individualized education and prescriptive teaching.

4. Behavioral modification strategies. Proceeding from the assumption that all behavior is learned, these strategies attempt to modify deviant behavior in specific ways through the use of appropriate reinforcement procedures. The chief orientation in American behaviorism has been the operant approach linked to Skinner, which entails an analysis of behavior, its antecedent conditions, and its consequences.

5. Medical and biophysical theories. These theories propose that deviations and disturbances in behavior and learning are related to biological disorders. Such problems can be as diverse as brain disorders or dietary deficiencies.

6. The ecological model. Based on the assumption that the cause of the disturbance is a disharmony between the youth and the environment, intervention focuses on changes both in the child and in the environment to improve their reciprocal relationships.

7. The counterculture movement. This view is critical of societal institutions. Children are seen as having great potentials, which could be realized if they were unfettered from the debilitating effects of current educational programs or the social and economic system.

8. The transcendental model. This approach is seen in a diversity of therapeutic communities in which a central tenet is the belief in the spiritual or even mystical nature of the human personality. An example is the Rudolph Steiner Anthroprosophic Movement, which originated in Europe.

9. The psychoeducational model. This model synthesizes other strategies. It is eclectic and holistic, drawing techniques from other models as they are deemed appropriate. The quality of the child’s total experience is seen as central to successful readjustment.

Juul documents examples of his various models as gathered from observations of schools and therapeutic facilities in 11 nations. These data led him to conclude that although theoretical categories may be distinct in rhetoric, it is difficult to identify pure examples of these models in practice. There are actually about as many models for intervention as there are programs. Juul concludes that most practice models are psychoeducational because explicitly or implicitly they tend to draw from several different educational and treatment frameworks. The specific model that purports to govern the operation of a program may be less important than the fact that intervention is organized around a distinct conceptual framework.

Juul notes strong national differences in the dominant models for intervention. Central and northern European nations are heavily influenced by the developmental principles of Pestalozzi. In the Frenchspeaking cultures, Freudian psychodynamic concepts and ecological orientations predominate. In contrast to European approaches, behavioral strategies are the most widely developed in the United States, particularly in the research literature. Actual practice in this country is characterized by a diversity of approaches drawing on a wide range of philosophical and theoretical formulations.

The abundance of theories can be confusing to the practitioner who is seeking for “the way.” Wolfgang and Glickman (1980) conclude that although all models have their critics, there is not now and possibly will never be research that documents indisputably the superiority of one model over the others. Thus, those working with troubled youth have available a wide range of strategies from which they can build an approach consonant with their personal philosophy and the needs of children and youth.