eBook - ePub

The Napoleonic Wars

The Empires Fight Back 1808-1812

Todd Fisher

This is a test

Share book

- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Napoleonic Wars

The Empires Fight Back 1808-1812

Todd Fisher

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In 1808 Napoleon dominated Europe, but the peace was not to survive for long. Todd Fisher continues his detailed account of the Napoleonic Wars with Austria's attack against Napoleon in 1809. Despite being defeated at Aspern-Essling, Napoleon rallied his forces and emerged triumphant at Wagram. With glorious victory behind him Napoleon now turned his attention to Russia and invaded in 1812. Yet the army was not the Grand Armee of old, and even the capture of Moscow availed him nothing--the foe remained elusive, the decisive battle remained unfought. This book tells the full story of the now legendary retreat from Moscow, as the fighting force that had vanquished Europe perished in the snows of the Russian winter.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Napoleonic Wars an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Napoleonic Wars by Todd Fisher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Weltgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The fighting

The Austrian campaign to the march on Moscow

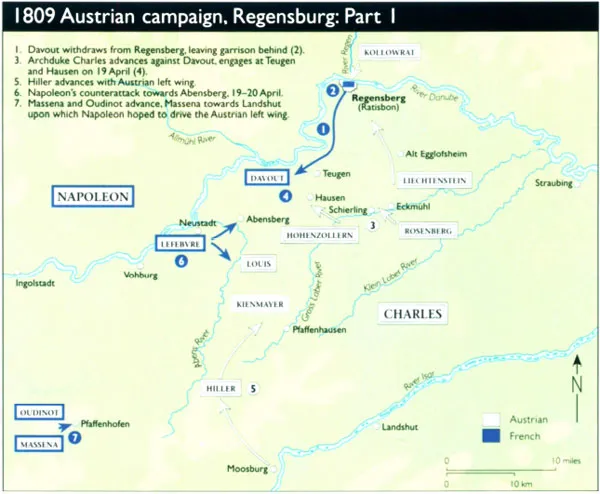

The Austrians invade Bavaria

With the decision to go to war made, Archduke Charles planned the main Austrian advance along the upper Danube River. The 1st through 5th Corps, along with the 1st Reserve Corps, would advance north of the river out of Bohemia. The 6th Corps and the 2nd Reserve Corps would advance south of the river from a starting position on the Bavarian border. When reports arrived that the French were beginning to concentrate in the Augsburg area, the specter of an unprotected Vienna being taken by a rapid advance along the south bank of the Danube caused Charles to rethink his plans. Accordingly, he shifted the main body of his troops south of the Danube to the Inn River line on the border with Bavaria. While this countered the perceived threat, the decision cost the Austrians one month of critical time. Even so, by 10 April 1809, the army was in position.

On other fronts, Archduke Ferdinand was to lead the 8th Corps and additional troops against Napoleon’s Polish allies in the Galicia region, while Archduke John with the 8th and 9th Corps would attack the French and Northern Italian army commanded by Napoleon’s stepson, Prince Eugene de Beauharnais. The Austrians believed that by applying broad and constant pressure, French resources would be stretched to breaking point.

Napoleon believed that he had until mid-April to concentrate his forces, but left Marshal Berthier instructions to fall back on the lines of communications should an attack come earlier. Berthier, a superlative chief of staff, struggled when commanding an army. When crucial orders from Napoleon were delayed, Berthier’s confusion only worsened.

Archduke Charles was considered the only general who could match Napoleon, but he was prone to inaction at the most inappropriate times. (Roger-Viollet)

In the early morning of 10 April, the leading elements of the Austrian army crossed the Inn River. The opposing cordon of Bavarians fell back, but bad roads and freezing rain delayed the Austrian offensive during the first week. The Bavarians made a brief stand on the Isar River at Landshut on 16 April, before once more retreating and yielding the passage of the critical river line. Beyond the Bavarians, only Marshal Davout’s 3rd Corps, deployed around Regensburg, remained guarding the key bridge over the Danube that linked the north and south banks.

Charles stopped to analyze the intelligence he had received on the evening of 17 April. By concentrating his forces north of the Danube and delivering a thrust from the south, Charles could drive Davout’s forces back and the whole of the French defensive position would come unhinged. The archduke ordered the two wings of the Wurttemberg army to converge on Regensburg, but his plans had to be altered the following day when he learned that Davout was heading south along the Danube and attempting to link up with supporting French corps further to the south and west. Davout had been placed in this precarious position through a combination of bad luck and poor timing, and Charles had a golden opportunity to crush the ‘Iron Marshal’ by pinning his 3rd Corps against the river.

The arrival of Napoleon

Napoleon arrived at Donauworth, the French headquarters, on 17 April 1809. He immediately began to assess the disastrous situation facing his army. Until now the French army had been badly out-scouted by the numerically superior Austrian cavalry. The most reliable reports were coming from spies and civilians reporting to Davout’s men. The 3rd Corps was clearly in extreme danger, and aid could not arrive for a couple of days. The best solution seemed to be for Davout to abandon his position around Regensburg and link up with the Bavarians further to the east. Unfortunately, when these orders from Napoleon arrived, Davout required an additional day to gather up his corps as they were scattered and fatigued from marching and counter-marching as a result of Berthier’s confused orders. Davout set off early on the morning of 19 April to link up with his allies.

Davout’s 3rd Corps moved south out of Regensburg on the direct road that ran along the Danube and toward Ingolstadt. In the initial stages of this maneuver his corps, formed in two parallel columns of march, were strung out with no line of retreat if the Austrians attacked from the east. Davout had left a regiment behind the walls of Regensburg to prevent any passage of the Danube by the Austrians and to protect his rear. Charles’ plan of attack was to wheel with his 3rd Corps attacking along the Danube while the 4th and 1st Reserve Corps swung on the pivot.

Teugen-Hausen

On the morning of 19 April, both armies got under way, the French with a two-hour head start. By 8.30 am, Davout had nearly escaped the trap. Two of his four divisions had moved past the choke point, but the marshal received word of strong enemy activity moving up from the south and his supply train was not yet through the key village of Teugen. The Austrian 3rd Corps, under Field-Marshal the Prince of Hohenzollern, was rapidly arriving upon the battlefield and trying to cut them off. This force had been partially weakened out of fear that the Bavarians might fall upon their flank so more than one division had been detached to act as a flank guard. These men would be sorely missed in the day’s contest.

The action opened with the French skirmishers being thrown back toward Teugen as the advance guard of the Austrian 3rd Corps crashed forward. Davout, realizing that his flanks were in peril, sent the 103rd Line forward to buy time and give the remainder of St Hilaire’s division a chance to deploy. He sent them in skirmish order toward the town of Hausen and the 6,000 Austrians waiting for them. At the same time, Davout ordered Friant’s division to advance to St Hilaire’s left and support the effort. Friant had his own problems: elements of the Austrian 4th Corps were going in to the attack as well. However, fortunately for the French, at the rear of the column, General Montbrun’s cavalry would mesmerize Field-Marshal Rosenberg’s 4th Corps for most of the day.

The men of the 103rd were doing well considering they were outnumbered three to one and all the artillery on the field was Habsburg. As they finally gave way, the Terrible 57th’, arguably the finest regiment of line infantry in the French army, swung into action. They took a position upon the ridge overlooking the town and the Austrian assault ground to a halt.

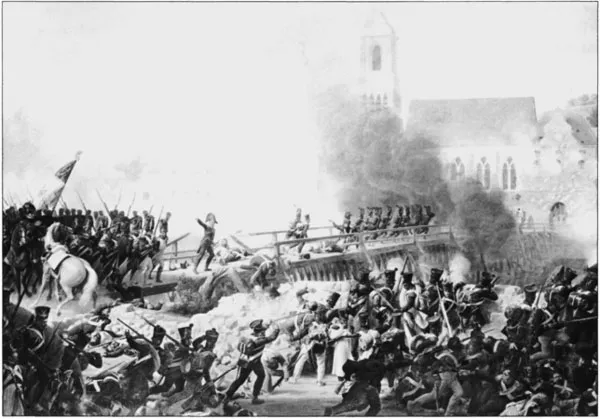

One of Napoleon’s aides. Mouton, stormed the bridge at Landshut despite the defended barricade and buildings. Napoleon was so impressed he punned. ‘My Mouton (sheep in French) is a lion.’ (Roger-Viollet)

Now checked, the Austrians failed to see the 10th Light Regiment creep up through the woods. This elite force fell upon the Austrian artillery and drove it from the field. Hohenzollern committed some of his reserves in response to this reverse, and as the white-coated Austrians came forward, they tipped the balance back to their side in this running fight. Davout had to commit all available troops on the field to stem the tide.

Sensing victory, more Austrians were released and this time cavalry charged the beleaguered 57th, which lay down a withering fire and formed square with its flank battalion. The battered cavalry withdrew and played no further part in the day’s actions. Under the cover of this cavalry assault, a fresh regiment came up to attack the French line. The Manfredini regiment advanced in column through a swale in the ground and turned on the flank of the 57th. Fortunately for Davout, General Compans saw what was about to happen and led newly arriving troops forward. The two columns collided and the French came off better. The Austrians fell back, rallied, and came on again, led by the dashing General Alois Liechtenstein. The 57th, out of ammunition, finally gave way. The French fell off the ridge and down to the town of Teugen. There Davout rallied the men and, sending in his last reserve, retook the ridgeline. The Austrians were almost completely played out on the ridge, when Friant’s men appeared upon their right flank. This was too much, and the Habsburg line gave way. Streaming down the ridgeline toward the town of Hausen, they rallied behind the last reserves that Hohenzollern had to commit on the field.

Once more General Liechtenstein led the attack, carrying the Wurzburg regiment’s (IR 3) flag to inspire the men, and stormed the woods. While his attack drove back the French line, more of Friant’s men and the arrival of the long-awaited French artillery restored the situation. For his efforts, General Liechtenstein lay severely wounded. The Austrians had retreated behind the protection of their guns deployed in front of Hausen when a violent thunderstorm started and the battle ended.

Davout had defeated a force twice his size and had been able to re-open communications with the rest of Napoleon’s army. Charles had spent the battle only a couple of miles away with a reserve of 12 elite grenadier battalions. It is difficult to determine who was at fault for the failure to commit these troops. Clearly, communication was poor, but the blame must be shared between Hohenzollern for not begging for the men and Charles for not finding out what was happening to his front. As it was, the Austrians knew they had fought well but had still lost: demoralization began to set in.

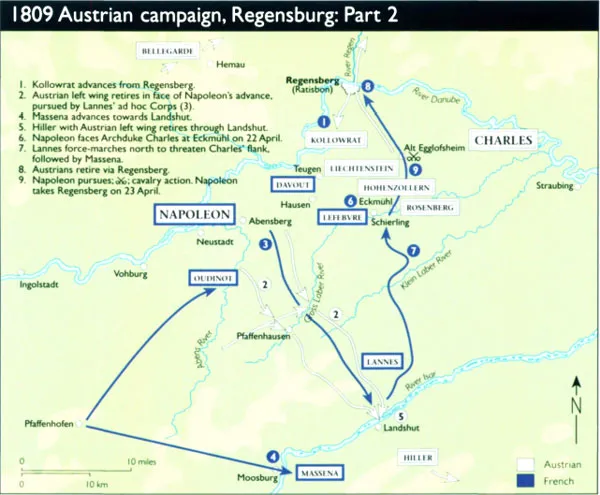

As the battle of Teugen-Hausen was drawing to a close, Napoleon switched to the attack. He ordered Marshal Masséna’s 4th Corps to advance on Landshut. Masséna advanced from Ingolstadt with the heavy cavalry, linked up with the Bavarians and Wurttembergers, and ordered the 2nd Corps to hurry to the front. By 9.00 am the following day he was in place. To give him even more flexibility Napoleon made an ad hoc corps from two of Davout’s divisions and placed it under Marshal Jean Lannes, who had just arrived from Spain. Davout and his two remaining divisions would press the forces in front of him.

Napoleon’s plan was to drive the Austrians back to Landshut, which he assumed was their line of communication. There they would be pinned by Masséna’s Corps coming up from the south.

The battle of Abensberg, 20 April 1809, was a running battle, with the Austrians being driven back throughout the day. By nightfall the Austrian 5th, 6th, and 2nd Reserve Corps were well on their way to Landshut. They arrived the following morning, having marched through most of the night. General Hiller, commander of the Austrians in this sector, did his best to put them in good defensive positions.

Napoleon was close on their heels. At Landshut, on 21 April, Napoleon assembled his forces and attacked through the town and over the two bridges that spanned the Isar River. This daring assault saw more than 8,000 Austrians surrounded and forced to surrender in the town. Strategically the attack may have been irrelevant, because the Austrian position had already been flanked by the French 4th Corps. Masséna’s men crossed over the river quickly, closing on the position from the south. They narrowly missed cutting off the retreating Austrians who had been foiled by bad roads, a lack of initiative in the aging marshal, and pockets of determined enemy resistance. Compromised by the hard-driving French offensive, this Austrian wing fell back to the east and to the next defensive line.

Davout (Job). At Auerstadt in 1806 and at Eckmühl in 1809 Davout proved to be tough enough to score victories over superior numbers of enemies. (Edimedia)

Early next morning, Napoleon received the last of several desperate messages from Davout. This time the news was delivered by the trusted General Piré, who finally managed to persuade the Emperor that he did not face the main Habsburg army. Napoleon now grasped that his left flank stood in the greatest peril.

Throughout 21 April, Davout attacked the retreating Austrians with the help of a Bavarian division under Marshal Lefebvre. The further back the Austrians fell, the stronger their line became, for in fact they were falling back on their main force. General Montbrun’s cavalry, off to the north, was reporting massive formations heading Davout’s way. The combat on the first day of the Battle of Eckmühl, as this fight was to become known, was sharp, with each side giving as much as they took. However, that night Davout faced a terrible predicament. While a fresh division had come up to his support and the artillery train would be present for any fighting in the morning, his infantry was low on ammunition. Davout knew that at least three Austrian corps remained in front of him. In fact the situation was even more desperate than he realized, for Regensburg had fallen and two more Austrian corps would be able to cross the Danube and enter the fight.

The outnumbered Austrian cavalry attempted to delay the pursuing French.

Charles saw this great opportunity, but his spread-out army would take half a day to get into position. He, like his opponent, was reading the situation wrongly. He assumed that Davout was the leading element of the main French army. Charles’ forces were aligned on a north-south axis, and his reinforcements were coming from the north, through Regensburg. If the plan worked, his new arrivals would fall upon the French far left flank. The archduke wanted the two wings of his army to coordinate with each other, so he would allow the French to expend themselves upon his defensive position around Eckmühl and take no offensive action himself until his reinforcements were in position.

Eckmühl

As dawn broke on 22 April, the two sides faced each other and except for some skirmishing, neither side made an attack. Morning turned to midday and still an uneasy calm hung over the battlefield.

While Charles looked for signs of his 2nd Corps, Davout had a better grasp of the developing situation. Napoleon had sent General Piré back with the message that the Emperor was coming with his army. Davout was to maintain contact and expect Napoleon to launch his attack at 3.00 pm. Every minute that Charles delayed increased the marshal’s chances of survival and victory.

At about 1.00 pm the leading elements of the Austrian attack collided with Montbrun’s cavalry. The hilly and wooded terrain great aided the French in slowing down the impetus of the attack. As the French horsemen retreated, the Austrian commander of the left flank, General Rosenberg, felt concern as he observed Davout’s main force opposite him. Instead of quickly shifting to meet the threat caused by Charles’ attack, they remained in place and were watching him! Rosenberg knew this could mean only one thing. He began to shift troops to meet a threat from the south. It was not long before his suspicions were confirmed. His small flank guard had caved in under a massive French force that was heading his way.

Napoleon had achieved a most remarkable march, one of the finest examples of turning on an army’s axis in all of history. After receiving the intelligence at around 2.00 am he had set into motion the orders to turn his army to the north and to march the 18 miles to the help of his beleaguered marshal. In short order, the plans were set in motion. Remarkably, Napoleon would arrive even earlier than promised.

The tip of his hammer blow was General Vandamme and his Wurttemberg troops. These Germans came on with the greatest élan. Led by their crack light battalion, they stormed across the bridge at Eckmühl and into the town. There they seized the chateau despite dogged Austrian resistance.

As the first of Napoleon’s attacks got under way, Davout launched his own attack against the center of Rosenberg’s position, the village of Unterlaiching and the woods above. Davout had sent in the 10th Legere to carry out the task. This elite unit paused only momentarily in the village before continuing on against the woods. There they faced several times their own number, and a vicious fight ensued tree to tree. Eventually, Davout reinforced the...