![]()

1 Excavating away the ‘poison’: the topographic history of Butrint, ancient Buthrotum

Richard Hodges

Modern history was born in the nineteenth century, conceived and developed as an instrument of European nationalism. As a tool of nationalist ideology, the history of Europe’s nations was a great success, but it has turned our understanding of the past into a toxic waste dump, filled with the poison of ethnic nationalism, and the poison has seeped deep into popular consciousness. Clearing up this waste is the most daunting challenge facing historians today.

Patrick Geary1

Inhabited since prehistoric times, Butrint has been the site of a Greek colony, a Roman city and a bishopric. Following a period of prosperity under Byzantine administration, then a brief occupation by the Venetians, the city was abandoned in the late Middle Ages after marshes formed in the area.

UNESCO World Heritage List: Butrint2

The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Butrint for much of its recent history has been a subject of nationalist interpretation.3 Dissect UNESCO’s 1992 inscription, as we shall do later in this chapter, and it is clear that the World Heritage Centre imbibed the ‘poison’ Patrick Geary describes as a trait of nationalism. Little interest has been expressed by this global arbiter in Butrint’s larger Mediterranean context. Instead, UNESCO, following closely the largely nationalist conclusions drawn by Italian, Greek and Albanian archaeologists, focussed upon its location and apparent continuous history in terms of the contemporary texts associated with it.4 These texts have been deployed to define it as Greek, Roman, Christian, Byzantine, and briefly Venetian, omitting an Ottoman presence altogether. It might be exaggerated to describe this as a toxic history (to use Geary’s term), but the Butrint Foundation excavations made between 1994–2009 show that the changing topographic character of the site differs markedly from its reduction to a place of enduring occupation until the environment contributed significantly towards terminating town life.

As we shall see, Butrint for much of its history belonged to the wider conditions of the Adriatic Sea (Fig. 1.1). More specifically, it was either an outlier on the Epirote coast of Corfiot interests or a stronghold on the Straits of Corfu deliberately challenging Corfiot interests. This much was in evidence when Butrint and Cape Styllo to the immediate south were unexpectedly apportioned to the new republic of Albania in August 1913 at the Treaty of London after the Great Powers succumbed to aggressive Italian diplomatic pressure and agreed that the Straits of Corfu, being of such crucial strategic importance, should not be controlled by one nation state, Greece, but by two: Albania (on the Epirote side) and Greece (on the Corfiot side).5 This decision in the summer of 1913 inadvertently created a historical place for Butrint. First, it was isolated in a no-man’s land on the southern border of the new republic of Albania in a largely Greek-speaking territory, then since 1992, in post-communist times, Butrint has established a renewed relationship with Corfu insofar as tourists from the Greek island, mostly on day tours, provide significant income to Albania’s premier UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Butrint Foundation project, launched in 1993 (and in the field in 1994), described in this volume took its point of departure from the previous studies of Butrint, principally the 1928–40 Italian mission and the post-war socialist excavations. These earlier excavations, as is discussed below, were undertaken with explicit nationalist motives. No less significantly, large areas within Butrint were excavated by teams of workmen but very little of the excavated evidence was reported upon.6 Almost no stratigraphic records from pre-1992 were published, and most reports from these Italian and early Albanian excavations pay little attention to associated finds. Instead, the interpretation of Butrint’s long history before 1992 rested primarily upon interpretations of the architectural, artistic and largely undated topographic elements found at the site. On occasions epigraphic evidence was used to affirm interpretations of Butrint’s history.

By contrast, our point of departure for the excavation methodology was Martin Carver’s Arguments in Stone that readily assumed (as we did) that a north European methodology (rooted in north European historiographic traditions) might be easily translated to a Mediterranean context.7 As in many similar projects, such an assumption was soon to be dispelled. First, our Albanian collaborators, as we have recorded elsewhere, had their own historical paradigm rooted in sustaining a national myth that took no account of contemporary historiography.8 Second, although our approach involved sampling on a major scale, identifying stratigraphic deposits as predicated by Carver’s method, this was complicated by tree cover, by the changing and high water table, and most of all by the realization that only open-area excavation with an immense commitment to labour and post-excavation analysis offers a suitable instrument for interpreting inter-period and intrasettlement differentiations.

Figure 1.1. View of Butrint, Lake Butrint and the Straits of Corfu from Mount Mile

Put more baldly, Carver’s method, which advocated small-scale excavation to solve specific problems of urban topography, together with computer-generated simulations known as ‘deposit modelling’ between excavated samples, did not work in the context of late antique and medieval Butrint. Problems of residuality, the repeated remodelling and re-use of structures throughout the Roman period and the large-scale secondary movement of deposits in antiquity (during construction work and terracing) meant that the results of keyhole archaeology were inconclusive at best and totally misleading at worst. As a result, our initial investigations from 1994–99, summarized in Byzantine Butrint, although dramatically increasing our understanding of Butrint, provided only an imprecise overview of the town and its changing topography.9

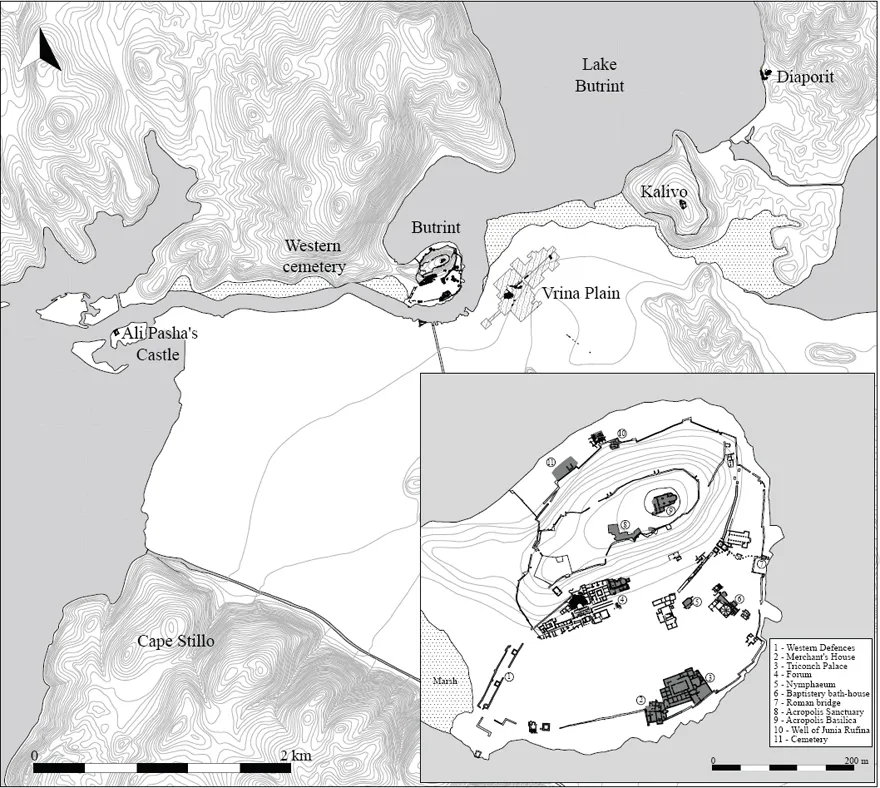

Many projects would have halted after this extensive range of investigations but, with support from the Packard Humanities Institute, from 2000–09 we developed a constellation of major excavations (Fig. 1.2). Large excavations were initially opened at the Triconch Palace to review a waterside sector of the city, and at the lakeside villa at Diaporit, identified in the field survey 4 km northeast of Butrint.10 Concurrently, we embarked upon a programme to identify the suburb of Butrint on the Vrina Plain, first by a new extensive geophysical survey (following initial surveys in 1996–1998) with an associated study of the environmental conditions, initially by test-trenching along a drainage dyke made in the 1960s, and then by making two large open-area excavations focussed upon two very different parts of the suburb.11 The combined area of the project’s excavation trenches covers approximately 8,250 m2.

These excavations, supported in particular by the remarkable knowledge and dedication of our ceramic specialists, Paul Reynolds and Joanita Vroom, have given us an entirely new understanding of the urban history of Butrint from its earliest occupation until the Ottoman age. Plainly, some of this approach evolved strategically to confront different period-based paradigms. However, our understanding of the 7th- to 12th-century history has been enhanced not always as a result of judgements taken to identify these periods but by serendipity, in that some of the most significant discoveries relating to the Byzantine Dark Age have been more by accident than design.12 How, we need to ask, are we to interpret this serendipity – bearing in mind of course, the same serendipity for the most part has determined the survival of the historical texts that form the framework for this period?

Serendipity entered into this as the chance arose to excavate a limited area in the centre of Butrint with a view to finding the Roman forum. Further opportunities then followed – (i) to explore a section of the acropolis prior to backfilling and landscaping the 1990–94 excavations as well as the eastern summit prior to landscaping, (ii) to excavate ahead of conservation of the Western Defences, and (iii) to investigate an area adjacent to the well of Junia Rufina beside the northern postern gate, known as the Lion Gate.13 These new excavations, executed with a knowledge gained from the excavations at Diaporit, the Vrina Plain and the Triconch Palace, have been particularly important for developing a new understanding of the Byzantine period. Based upon these new excavations, we have re-examined many of the standing monuments, including the fortifications, the Great Basilica and, in so doing, discovered close to the Water Gate the remains of a Roman bridge.14

Figure 1.2. Map showing the location of the Butrint Foundation excavations and geophysical survey, 1993–2010

There has been, in other words, a sequence of investigations that initially followed a strategy of the kind propagated by Carver, which serendipitously gave rise to excavation opportunities, which in turn have lead to the development of new field strategies. In this chapter, we shall examine the topographic evidence arising from this mixture of approaches to Butrint, culminating in a proposed new paradigm for the history of the site.

Changing paradigms

Colonel William Martin Leake was by no means the first to take an interest in Butrint’s archaeological remains, but his account laid the foundations for subsequent research of ancient Buthrotum.15 His visit by boat in 1805 was not published for thirty years, but the ample and romantic description of the ancient city located in this marginal maritime environment almost certainly served as an impetus and guide for the Italian prehistorian Luigi Maria Ugolini’s first visit in 1924. Ugolini was no less of a romantic than Colonel Leake. On behalf of his government, Ugolini’s task was to establish an Italian archaeological presence in Albania in effect to compete with the new French archaeological project at Apollonia near Albania’s oilfields.16 But Ugolini proved a master at sustaining his political obligations while pursuing a contemporary research agenda. He tells us in the preface of his Butrinto. Il mito d’Enea, gli scavi – a monograph he dedicated to Benito Mussolini – that he wished to emulate Heinrich Schliemann, the excavator of Mycenae and Troy by unearthing a place associated with the mythic figure, Aeneas.17 Unsa...