eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

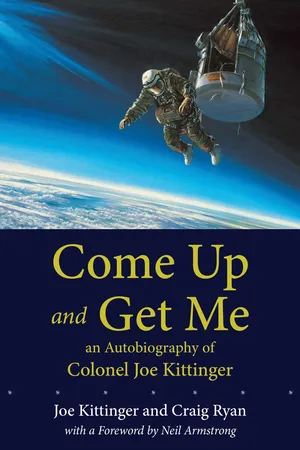

Come Up and Get Me

An Autobiography of Colonel Joe Kittinger

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 31 Dec |Learn more

About this book

A few years after his release from a North Vietnamese prisoner-of-war camp in 1973, Colonel Joseph Kittinger retired from the Air Force. Restless and unchallenged, he turned to ballooning, a lifelong passion as well as a constant diversion for his imagination during his imprisonment. His primary goal was a solitary circumnavigation of the globe, and in its pursuit he set several ballooning distance records, including the first solo crossing of the Atlantic in 1984. But the aeronautical feats that first made him an American hero had occurred a quarter of a century earlier.

By the time Kittinger was shot down in Vietnam in 1972, his Air Force career was already legendary. He had made a name for himself at Holloman Air Force Base near Alamogordo, New Mexico, as a test pilot who helped demonstrate that egress survival for pilots at high altitudes was possible in emergency situations. Ironically, Kittinger and his pre-astronaut colleagues would help propel Americans into space using the world's oldest flying machine--the balloon. Kittinger's work on Project Excelsior--which involved daring high-altitude bailout tests--earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross long before he earned a collection of medals in Vietnam. Despite the many accolades, Kittinger's proudest moment remains his free fall from 102,800 feet during which he achieved a speed of 614 miles per hour.

In this long-awaited autobiography, Kittinger joins author Craig Ryan to document an astonishing career.

Selected by Popular Mechanics as a Top Book of 2010

By the time Kittinger was shot down in Vietnam in 1972, his Air Force career was already legendary. He had made a name for himself at Holloman Air Force Base near Alamogordo, New Mexico, as a test pilot who helped demonstrate that egress survival for pilots at high altitudes was possible in emergency situations. Ironically, Kittinger and his pre-astronaut colleagues would help propel Americans into space using the world's oldest flying machine--the balloon. Kittinger's work on Project Excelsior--which involved daring high-altitude bailout tests--earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross long before he earned a collection of medals in Vietnam. Despite the many accolades, Kittinger's proudest moment remains his free fall from 102,800 feet during which he achieved a speed of 614 miles per hour.

In this long-awaited autobiography, Kittinger joins author Craig Ryan to document an astonishing career.

Selected by Popular Mechanics as a Top Book of 2010

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Come Up and Get Me by Joe Kittinger,Craig Ryan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: The Gift of Adventure

I grew up in paradise on the St. Johns River in the lowlands of central Florida. The river was my lifeline. The slow-moving water as well as the wildlife and the society of men who lived and worked and played on it taught me much of what I was going to need to know about the world. Most and best of all, it gave me the precious gift of adventure.

The St. Johns slides under State Highway 50 at a bridge east of Orlando. About a quarter-mile farther east, a tributary veers off and cuts under another bridge, and right there a haphazard little structure perched on pilings above the water: Lamb Savage’s Fish Camp. My father would take me down there nearly every weekend. Dad owned a 34-foot ramshackle houseboat he christened the John Henry, and we stayed on the boat whenever we went to Lamb Savage’s. It had four bunk beds in back and a little cubbyhole under the front deck where a boy my age could curl up and sleep.

The boat, made mostly of cypress, wasn’t much to look at—imagine a steamship on top of a box. There was a crude steering apparatus hooked up to the 10-horsepower Evinrude, and the boat was controlled with a wheel in the front. But since we didn’t have a remote-controlled throttle, engine speed was adjusted manually at the captain’s command. It was all about teamwork. The kitchen consisted of a Coleman gas stove, and lighting was supplied by a gas lantern. There was an icebox for beer and cold drinks. We had screens on the windows, which could be opened for ventilation, but most of the time passengers rode on the boat’s roof, which sat about 15 feet above the water line and provided not only a perfect viewing platform during river trips, but a great spot to sit and cast for black bass. The flat-bottom John Henry, in spite of its lack of sophistication, was the perfect vehicle for the lazy, shallow St. Johns, and it gave us just about all the fun we could handle.

My father, Joe, who had his own office equipment business, was the source of everything my younger brother and I knew about hunting, fishing, camping, and the ways of nature. The best times on the river were the spring and the summer, when my mother, Ida Mae, would join us. Over the years, she worked as a nurse’s aide, a secretary, an executive assistant, a restaurant owner, a florist, and finally a real-estate broker. She also raised two boys during the Great Depression. She was a true Christian and had an exceedingly generous nature. Whenever hungry people knocked on the door, she was always happy to share food from our table. She was a great southern cook and could whip up a meal at a moment’s notice. When she’d join us on the John Henry, we’d get biscuits and hush puppies to accompany fried chicken or the meat we’d bring in from our expeditions: frog legs, turtle steak, and a variety of fish. Her meals definitely beat the canned stew we ate when she wasn’t along.

I was born in Tampa in 1928, and three months later we moved to Orlando, which was a nice little city of thirty thousand at that time. It was an agricultural area, the heart of America’s citrus industry. My brother, Jack, came along a couple years later. We lived in a middle-class neighborhood with a good public school down the street. My mother believed that an education was a necessity. She made sure we had library cards, and if we weren’t playing outside, she expected us to be reading a book. She pushed us to join the Boy Scouts, too, but for me there was nothing quite like the river. My river.

Lamb Savage’s was where it all happened. Lamb himself was a fourth-generation Florida cracker who lived off the land much as his forefathers had. He hunted game with a single-shot .22 rifle, caught alligators, turtles, and fish, and grew his own vegetables on the rich bottomland along the riverbank. Old Lamb didn’t own a car or a truck, but once a year he’d convince a friend to haul him over to the Atlantic coast to get his year’s supply of sea salt. He dressed in whatever used clothes he could find. You could spot him from a distance in his trademark bandana and ragged old hat.

Lamb’s camp offered boat rentals—they always leaked—and a genuine old-time juke joint where a nickel jukebox played scratchy old 78s. We’d tie up near the south side of the road next to the fish camp, and on a Saturday night we could hear the twang of the steel guitars and fiddles and the laughter and the clink of beer bottles into the wee hours. If I’d had a quarter for every time I heard Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys strike up “San Antonio Rose,” I could have bought the whole place. There wasn’t much of a menu: beer, pepperoni sticks, pickles, and pickled pig’s feet, but it was always an adventure at Lamb’s. And, of course, every now and then a fight would break out. When that happened, the one guy you didn’t want to tangle with was Lamb himself. This was common knowledge. He once bit off a guy’s thumb during a disagreement. But there were other dangers. The joint had a back door that opened directly above the river. One winter night a guy not familiar with the place opened that door and stepped outside—and disappeared into space, free-falling 30 feet right into the cold water. It couldn’t have been too pleasant. The other thing that opened directly onto the river was the fish camp toilet.

On the St. Johns. My mother, Ida Mae, poses with the inimitable John Henry near Lamb Savage’s Fish Camp.

Saturday afternoon was prime drinking time at Lamb’s. We usually were several miles away at that time of day, fishing or hunting or scouting places to fish and hunt. But one Saturday we were tied up to the mooring, taking in the festivities, when a notoriously prodigious drinking man from Orlando named Ed Spivey got the notion to try and run his boat through the bridge pilings at full speed. Try being the operative word. Spivey got a good running start and hit the bridge head-on at 30 miles per hour, obliterating his boat, which immediately sank in front of an audience of a couple dozen amused bystanders. Ed just bobbed up, swam to shore, and grabbed another beer, laughing and whooping the whole way. One of the onlookers dived into the river and managed to retrieve the only salvageable item, the 22-horsepower engine. It wasn’t the sort of performance that much fazed anybody at Lamb’s. But I paid attention.

Guts and smarts, it was clear, didn’t necessarily go hand in hand.

My father, who worked long hours during the week, taught me what he could on our weekends on the St. Johns. I learned the mysteries of the river and became a pretty fair boatman. We had a little 12-foot john boat we’d use for duck hunting. We’d pull the motor off the John Henry, stick it on the duck boat, and off we’d go. One day when I was eleven, my father offered me the chance to transport a couple of drunken fishermen a few miles upriver to where they had their boat tied up. I was proud to get the assignment, but I was a bit worried about these particular guys. Three people was the maximum load that poor little boat could handle, and I was worried about it tipping over if the men became unruly. Before I pulled out into the current, I told my passengers that they’d have to stay seated so as not to unbalance things. I was in charge, and I wasn’t shy about letting them know it.

We’d gotten only about 30 feet from shore when one of the guys stood up and started swaying back and forth. I guess he thought it was funny. It was just a few seconds before the duck boat flipped us all into the water. We had to take the Evinrude apart and dry out the ignition coil before we could get it started again. I have no idea how the two men finally got to their own boat, but it wouldn’t have bothered me if they’d had to swim the whole way.

The St. Johns was like a hundred-headed hydra with tributaries and sloughs running off at every crazy, twisty angle. When the water was high, navigation could be a serious challenge. You really had to know the channel of the river. And, of course, the difficulty was compounded at night. One evening we made our way about 10 miles upriver from Lamb Savage’s to a spot called Long Bluff. My father had three of his fishing buddies with him, and at about ten o’clock they ran out of beer. I was asked to take the duck boat back to Lamb’s and get them another case—exactly the kind of job I coveted. It was a hot Saturday night, and by the time I got there, the juke joint was packed, and the place was really jumping. I couldn’t legally go inside, so I asked the soberest man I could find to help me. He went in, and a few minutes later Lamb Savage himself came out. He looked down to where we usually moored and, failing to see the John Henry, asked me where I’d come from. I explained that I’d made my way downriver in our little duck boat to get beer. I don’t think he believed me at first. Even an experienced river rat, he said, would have trouble with that stretch of the river at night. He squinted and scratched his chin. Finally, he agreed to sell me the beer but decided he probably ought to escort me back to Long Bluff himself.

I held my ground.

“Listen, Mr. Savage,” I told him, “I had no trouble getting here from Long Bluff and don’t expect to have any trouble going back.” I pointed out that even if I had engine trouble or got confused about where the main channel was, I could always just drift back on down to the juke joint.

“I can take care of myself, sir,” I said.

Old Lamb finally agreed to let me go, and for years afterward he told the story of the little red-headed kid and the famous beer-fetching run down one of the trickiest stretches of the St. Johns in the black of night. Even though the beer run was no big deal to me, it became kind of legendary among the men who hung out at Lamb’s—and, naturally, I enjoyed the notoriety. I always privately thanked my father for giving me the chance—on that occasion and on many others over the years—to show what I could do. It’s the kind of thing that helps a boy grow up.

A little later I made another of those trips with my father and his fishing friends. This time Jack was along, and the two of us slipped away for some gator hunting. We caught a little 2-foot gator, tied some fishing line around its snout, and brought it back to the big boat to show it off. By the time we got there, though, the men were already sleeping off their beer. It was a steamy evening, and they were dozing in their shorts. A man named Frank Morton was stretched out on the upper bunk at one end of the boat, dripping with sweat. I snuck up and plopped the gator down on his bare stomach. It took Frank a few seconds to come to, but when he opened his eyes and saw that gator wiggling on top of him, he bolted upright and jumped right into the river. The other men woke up, found my brother and me howling with laughter, and saw Frank climbing back up onto the deck. By this time, the fishing line had come loose from the gator’s jaws, and that’s the first thing Frank saw as he climbed aboard—an alligator hissing and snapping right in his face. He jumped right back into the river. Funny thing is, Frank never accompanied us on another one of those fishing trips.

Gator hunting was a favorite past-time for my brother and me. We never saw too many big ones because back then they weren’t a protected species. The mature ones had a taste for livestock, so the farmers and ranchers weren’t too inclined to let them get very big. They’d usually shoot a big alligator if they saw one. I once saw a gator eat a cattle dog swimming across the St. Johns. The gators could be voracious. My brother and I would usually go at night, using a spotlight to attract them. If we saw one on the bank during daylight hours, one of us would make a commotion with our oars in the water, and the other would sneak up behind the gator and grab its snout to keep the jaws shut, making sure to secure the tail at the same time. We knew what we were doing, and neither of us ever made a serious mistake with an alligator.

These river trips weren’t all fishing and gator wrestling and frog gigging, though. Another major s...

Table of contents

- Foreword

- Prologue

- 1: The Gift of Adventure

- 2: Ace of Spades

- 3: Come Up and Get Me

- 4: Escape from Near Space

- 5: Combat

- 6: Hanoi

- 7: Home Skies

- 8: Destination: Unknown; Fuel on Board: Zero

- 9: Ballooning and Salooning

- Epilogue

- Awards and Honors

- Acknowledgments

- Index