![]()

CHAPTER 1

IMHOTEP

The man who became a god

We begin our search with a non-royal, but certainly not an ordinary man. Imhotep is one of the world’s first known inventors, credited as the architect of King Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara, the first monumental building made of stone anywhere in the world. Centuries after his death, from the New Kingdom onwards, Imhotep was remembered as a polymath, and associated in particular with writing and healing. Ultimately his name would come to be better known than that of all but very few pharaohs; although from the earliest times the cult of the deceased pharaoh was maintained by the placement of offerings at the chapel or other cult building(s) associated with the tomb, in reality the practice probably ceased in the case of most pharaohs within perhaps a few generations at most. Imhotep’s cult, by contrast, seems to have gained momentum over time; while there is no extant mention of his name in any text from the period following his death until the reign of Amenhotep III of the 18th Dynasty, it seems that by this time libation offerings were commonly made to him, indicating his status as a demi-god. By the 26th Dynasty, this status was clearly established, with the construction of a chapel devoted to his cult at Saqqara. The historian Manetho, writing during the Ptolemaic Period (see pp. 19–21), noted that Imhotep was ‘the inventor of the art of building with hewn stone’ and also that he was associated with Asklepius, the Greek god of medicine, and ‘devoted attention to writing’, aligning him with the Egyptian gods Ptah and Thoth.1 In more modern times, he has lent his name to the villain played by Boris Karloff in Hollywood’s The Mummy (1932). This Imhotep was revived in the public imagination with the 1999 re-make starring Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz.

One of the greatest figures in the emerging discipline of Egyptian archaeology, the British excavator W. B. Emery, dedicated the last years of his life to the search for Imhotep’s tomb, focusing his efforts at North Saqqara, close to the Step Pyramid. He uncovered a mass of evidence of the veneration of Imhotep and other deities associated with him in Ptolemaic and Roman times, concentrated on a cluster of tombs of the 3rd Dynasty. He seems to have come agonizingly close to locating the tomb of this great figure, and yet the clinching evidence eluded him, and he died before he could make what would unquestionably have been his greatest discovery.

Who was Imhotep?

Imhotep was undoubtedly the most successful non-pharaoh in achieving what all Egyptians wished for: to ‘cause his name to live’ – sankh renef, to use their phrase – in perpetuity. In other words, to ensure that he would be remembered, along with his achievements, for eternity, sustaining his existence in the afterlife. In fact, the memory of him took on a life of its own many centuries after his death. So how do we distinguish between the man and the legend?

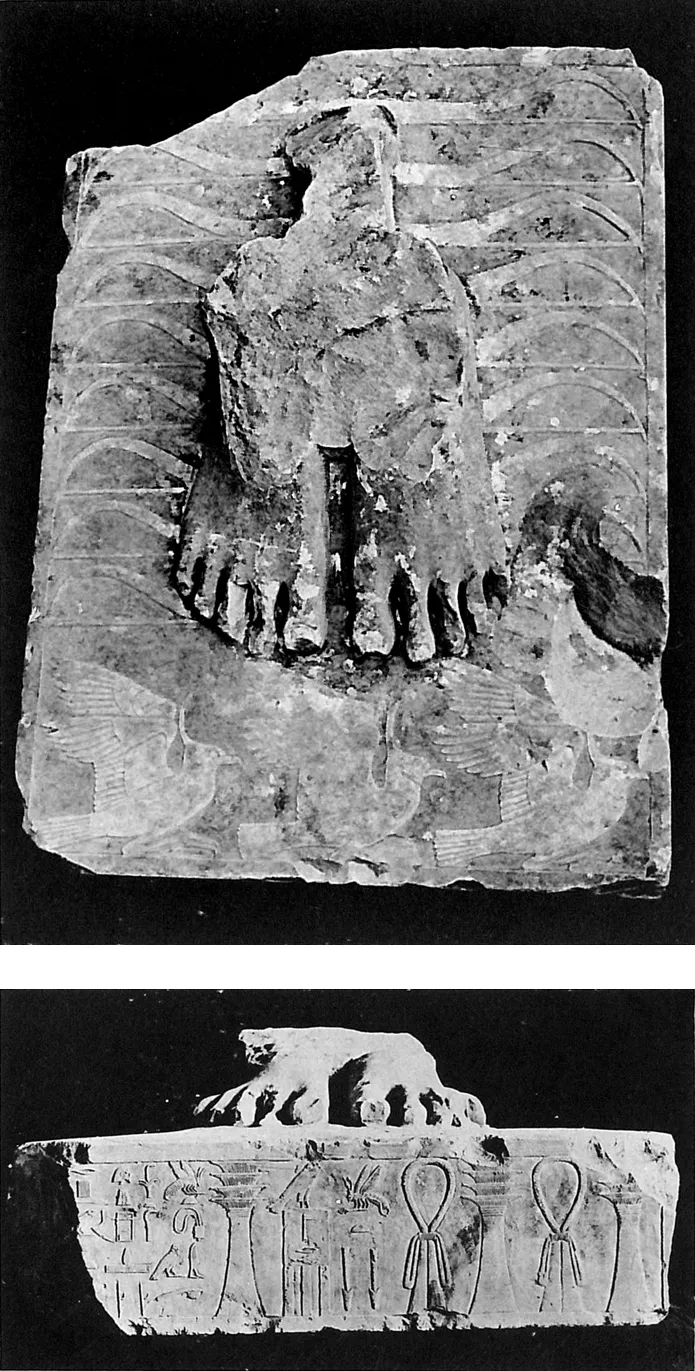

We will begin with what we know of the man. His name and titles are preserved on the base of a statue, now in the museum at Saqqara, of which only the feet remain.2 It probably depicted the king under whom Imhotep served: Netjerikhet, better known as Djoser, first ruler of the 3rd Dynasty. On this statue, Imhotep is given the titles ‘Seal-bearer of the King of Lower Egypt, Foremost one under the King of Upper Egypt, Ruler of the Great Mansion [i.e. the palace], the Noble, and Chief Priest of Heliopolis’,3 a repertoire that provides an indication of his rank and influence both at the court of the king and within the temple administration. This alone would be enough to show that Imhotep was among the most important men in the country, if not the most important after the king himself, but an intriguing phrase to the right of this text might indicate that he had even higher status vis-à-vis the king. It reads bity sensen or bity senwy, a very literal translation of which would be ‘the King of Lower Egypt, the two brothers’. This title appears to be unique to Imhotep, and is very difficult to interpret, but it has been suggested that it should be understood to indicate that he was the childhood companion, confidant, twin or even ‘alter ego’ of the king.4 In any case, the implication is that Imhotep was in some way the equal of the king, an extraordinary situation without parallel in ancient Egypt.

Statue JE 49889, which bears the name and titles of Imhotep on the base.

The statue base bearing his titles was found in close proximity to the Step Pyramid complex, and is among the admittedly scarce evidence firmly linking Imhotep to this pioneering monument.5 A group of seal impressions found in the mortar of the walls in the subterranean galleries of the pyramid and a group of stone vessels, also discovered in the subterranean part of the pyramid complex, similarly preserve some of the titles given on the statue, although not Imhotep’s name.6 Finally, his name appears on the northern enclosure wall of the mortuary complex of Djoser’s successor, Sekhemkhet, suggesting that his skills had been put to use in the following reign as well.7

The temple devoted to the cult of Imhotep at Saqqara seems to have been established no later than the 26th Dynasty, by which time his image as a god was firmly established: he was generally shown seated, wearing a long apron and tight-fitting cap, and with a papyrus scroll unrolled on his lap. The cap evokes the spirit of Ptah, patron god of artisans and architects, said to be Imhotep’s divine father. Imhotep, along with Ptah and Apis, would become the pre-eminent deity in the region of the capital city of Memphis, which lay at the head of the Delta, at the point where the Nile splits into multiple branches, and the junction between Upper and Lower Egypt. Apis, a manifestation of Ptah, was believed to be the son of the cow-goddess Hathor and the falcon-headed Horus. As Horus was the mythical king of Egypt, of whom each pharaoh was thought to be the living manifestation, Apis evoked some of the qualities of strength associated with pharaoh, who was often shown in human form but with a bull’s tail. Apis was believed to be manifest on Earth as a living bull of black-coloured hide, bearing a particular set of markings that would allow its identification by the priesthood. These bulls were worshipped at Saqqara, and upon the death of each animal an elaborate burial would be prepared, and the deceased bull lain, from the New Kingdom onwards, in a series of purpose-built catacombs known today as the Serapeum (after the Greek combination of Apis with Osiris, who was known as Serapis; see p. 206).

In addition to his familial connection with Ptah, and thus his living form as the Apis bull, Imhotep was aligned with Asklepius, the Greek god of medicine. By the 30th Dynasty, an Asklepieion (a temple dedicated to Asklepius and to his powers of healing) was built at Saqqara, at which Asklepius took the form of Imhotep. Is it possible that the temple may have been formed of, or at least built close to the location of, Imhotep’s tomb? A series of inscriptions at Saqqara dating to this period show that people were making pilgrimages from all around – ‘from the towns and nomes’ – to pray and to make offerings to the god so that he could cure their ills.8

Imhotep’s worship would continue into Roman times, and his name even survived into Arabic texts of the 10th century AD.9

Although Imhotep’s fame today rests largely on his legend having grown long after his death, it seems likely that, given the position he held in the royal court and in the graces of his king, he would have been lain to rest in a very substantial tomb. It is probable also that this would have been located in close proximity to the Step Pyramid, tomb of his king, Djoser, at Saqqara; Egyptian nobles often chose burial sites near to their pharaoh, even in these early days of the pharaonic era. However, despite extensive investigations at Saqqara by archaeologists for almost two centuries, and numerous tombs of the right kind and the right period having been uncovered, Imhotep’s has yet to be found – or yet to be identified, perhaps.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser, Saqqara.

The earliest monumental tombs

The Step Pyramid was a revolutionary leap forward in architecture and building, and apparently unique in its time. It seems to have set in train an astonishing sequence of similar leaps and innovations, culminating in the building of the first true pyramids, the crowning achievement among which was the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, built approximately half a century after Djoser’s pioneering monument.

The construction of private tombs had also become quite sophisticated by Imhotep’s time, and because we have investigated so many, we can build a reasonable picture of the kind of monument Imhotep may have had for himself. During the 1st Dynasty, the largest private tombs came to be marked at ground level by mastabas built of mudbrick, encasing a core of rubble and overlying the burial compartments below ground. A man named Merka who served under Pharaoh Qa’a, the last king of the 1st Dynasty, was buried in a particularly elaborate monument10 that established a series of features that would become typical of later tombs of high-ranking private individuals. He had his image, name and titles inscribed on a stela embedded in a niche at the southern end of the east side of the mastaba, and in an extensive building at the north end of the monument a pair of feet was found, representing the earliest evidence of a cult figure in a private tomb in Egypt. This combination of ritual emplacements – niches – at the northern and southern ends of the tomb became standard in private tombs of the 2nd Dynasty. By this period, the underground parts of these tombs had also become quite complex, and were typically entered via a staircase cut into the top of the mastaba.

By the 3rd Dynasty, mastabas for private individuals had come to be constructed on a massive scale, and the largest and most elaborate of the Saqqara monuments also display several innovations in the ritual parts of the tomb. The tomb of the confidant of the king and chief of scribes, Hesyra,11 provides the best example. It includes a number of new features that would become a standard part of Egyptian tomb design, exemplifying the sense of experimentation and creativity that characterizes the work of the designers and architects of the time. These innovations included the first attested false door, a decorative feature that was intended to allow the deceased passageway between the earthly and spiritual realms, and a full list of offerings, increasing the provision made symbolically to the deceased in the afterlife. In addition, a narrow corridor within the centre of the mastaba was lined down one side with niches incorporating wooden panels with raised relief images of the deceased, including hieroglyphic inscriptions allowing us to identify him by name; many of these tombs lack such inscriptions, and so remain anonymous.

The location of Imhotep’s tomb: Saqqara

Saqqara is clearly the prime candidate for the location of the tomb of Imhotep. It had been, along with Abydos, the most important cemetery in the country since the Two Lands had been unified at the beginning of the 1st Dynasty, and it was of course the cemetery that Imhotep’s king, Djoser, chose as his burial place. While Abydos had been the burial place of the pharaohs of the 1st Dynasty and some of the 2nd, and would remain an important site throughout Egyptian history, Saqqara was the cemetery attached to the capital city of Memphis. The funerary monuments of the courtiers of the time would have been very visible from the city, which lay below the desert plateau in the Nile Valley, the Step Pyramid being the grandest statement of all, a reminder to pharaoh’s subjects and any visitors to the capital of the king’s might. Saqqara is also home to a number of huge mastaba tombs of the time of Imhotep, the owners of quite a number of which have yet to be identified.

Bryan Emery’s excavations at North Saqqara. View looking northwest, towards the pyramids of Abusir.

Saqqara is a very large and very rich archaeological site, and was in use throughout Egyptian history, not just in the early days of the pharaonic era. The Step Pyramid itself lies in the centre of the necropolis, and the large mastabas of the first three dynasties lie to the north. The history of exploration and discovery at North Saqqara is long, and certainly not yet finished. Many different archaeologists and institutions have carried out separate campaigns in the area over the decades since it was first recognized as a site of considerable interest, and so reconstructing a plan of this part of...