![]()

Chapter one

YOUNG LUCIAN: ART IN WARTIME LONDON

He was totally alive, like something not entirely human, a leprechaun, a changeling child, or, if there is a male opposite, a witch.

Stephen Spender on the young Lucian Freud

In 1942, London was partially in ruins. Robert Colquhoun, a young painter who had arrived from Scotland the year before, was astonished by what he saw. ‘The destruction in the West End is incredible,’ Colquhoun wrote, ‘whole streets flattened out into a mass of rubble and bent iron.’ He noted ‘a miniature pyramid in Hyde Park’ constructed from the wreckage of destroyed buildings. One suspects that, like other artists, he found the spectacle beautiful as well as terrible.

Graham Sutherland, then one of the most celebrated British artists of the generation under forty, travelled into London by train from his house in Kent to depict the desolation. He would never forget his first encounter with the bombed City of London during the Blitz in the autumn of 1940: ‘The silence, the absolute dead silence, except every now and again a thin tinkle of falling glass – a noise which reminded me of the music of Debussy.’ To Sutherland’s eyes, the shattered buildings seemed like living, suffering creatures. A lift shaft, twisted yet still standing in the remains of a building, struck him as resembling ‘a wounded tiger in a painting by Delacroix’. This was a city under siege that had just escaped armed invasion. The arts, like every aspect of life, were rationed and much reduced. At the National Gallery, just one picture a month was on display.

Yet, amid the destruction, new energies were stirring. The war isolated London from the rest of Europe and exacerbated the endemic insularity of Britain as a nation. But new ideas were germinating in the minds of artists-to-be who were currently in the services, prisoner-of-war camps, schools or digging potatoes in the fields as conscientious objectors. A few, like Colquhoun, were already at work among the bomb sites of London.

In the same year in which Colquhoun penned his description of the ruined city, two young painters, just past their nineteenth birthdays, moved into a house on Abercorn Place in St John’s Wood in North London. It was a fine terraced building in the early nineteenth-century classical style. There were three floors, providing room for a separate studio each (the ground floor being occupied by a classical music critic who became increasingly irritated by his new neighbours). The tenants’ names were John Craxton and Lucian Freud. Neither was in the armed services: Craxton had failed the medical examination, while Freud had been invalided out of the Merchant Navy. And so, with financial support from a generous patron, Peter Watson, they were free to live la vie de bohème, Second World War-style.

Suitably enough, given the devastation that lay around, the environment that Freud and Craxton created for themselves was full of shattered forms, sharp-edged vegetation and the smell of death. The decor at 14 Abercorn Place was, as Craxton put it, ‘very, very bizarre’. The two painters would buy job lots of old prints at the nearby Lisson Grove saleroom, where fifty or sixty items would go for ten shillings. Among these were some that had nice frames, which they would keep, breaking up the rest and making a fire with them. ‘We’d lay the glass on the floor – a new sheet of glass for a special guest – so the entrance to our maisonette, [as] they were called, had dozens of broken sheets all over the floor which went crunch, crunch under your feet – which very much annoyed the man living underneath.’ The whole effect was completed by an array of headgear hung on hooks in the hall – ‘any sort of hat we could find’ – including police helmets, while on the upper floor there was a selection of ‘huge spiky plants that Lucian had growing up all over the place’. Freud also owned a stuffed zebra head, bought from the celebrated taxidermist Rowland Ward on Piccadilly. This was intended as an urban substitute for the horses he had loved since he learned to ride them as a child on his maternal grandfather’s estate outside Berlin. Various kinds of dead animals, not mounted or preserved, were favourite subjects for both Freud and Craxton. From time to time, the nostrils of the music critic were offended by a stench of decay wafting down from upstairs.

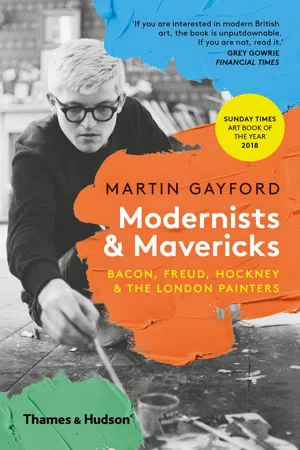

Lucian Freud, c. 1943. Photo by Ian Gibson Smith

Once, an important art dealer, Oliver Brown of the Leicester Galleries, made an appointment to inspect Craxton’s work in his studio. Unfortunately, however, the painter had forgotten the arrangement and was still asleep at his parents’ house. ‘Brown arrived wearing a bowler hat and carrying a briefcase and a rolled-up umbrella, rang the bell and, to his amazement, a naked Lucian, walking on this broken glass, opened the door.’ This apparition must doubtless have startled Mr Brown. From early on, Freud had struck people as a remarkable personality. Craxton remembered the sixteen-year-old Freud dropping in at his family home in the late 1930s:

Lucian was very on his own, reacting against everything. He horrified my parents, because he had an enormous amount of hair – a wild, untamed appearance – he was a very odd character in those days. My mother said, ‘My God, I don’t want any of my children looking like that’.

The photo editor Bruce Bernard – brother of the journalist Jeffrey and poet Oliver – met Freud during the war and was struck by his ‘exotic and somewhat demonic aura’ (Bernard’s mother, like Craxton’s, thought this youth might be dangerous to know). Freud’s earliest work, whether done from observation or from his imagination, had an intensity that marked it out as unmistakeably his. The critic John Russell, looking back on these years, compared the young Freud to the figure of Tadzio in Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice (1912), a ‘magnetic adolescent’ who seemed ‘to symbolize creativity’. In the circles around the periodical Horizon and its backer Peter Watson, ‘everything was expected of him’. But neither his true path, nor the importance of what he was eventually to do, would have been easy to predict in 1942. Who could have guessed that, to quote Bernard again, he would eventually become ‘one of the greatest portrayers of the individual human being in European art’.

Both the Freud and Craxton families lived in St John’s Wood, near Abercorn Place (hence Craxton’s choice to return to the family home every night to sleep). Harold Craxton, John’s father, was a professor at the Royal Academy of Music; Freud’s father, Ernst, was an architect and the youngest son of Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis. The Freuds had lived in Berlin, but left Germany shortly after the Nazis came to power. Consequently, Lucian had a privileged and cultured Central European upbringing until the age of ten, after which he went to a succession of progressive English boarding schools, getting expelled from all of them for wild behaviour.

Craxton and Freud were both from backgrounds that were highly unusual, in that the arts were seen as an integral part of everyday life. Elsewhere in London – and Britain – in the early 1940s, things were very different. To be an artist was a choice of career so rare as to be incomprehensible. According to Freud, ‘Being a painter in those days was not considered a serious occupation. When I told people at parties what I did, they would reply “I wasn’t asking about your hobbies”.’ At that time, he estimated, there were perhaps half a dozen painters in Britain making a living entirely from their work – Augustus John, Laura Knight, Matthew Smith and possibly one or two others. The big Edwardian portrait painters had done well for themselves, as the young Freud was aware: ‘Augustus John writes in his memoirs that William Orpen used to keep a plate of money in his hall for less fortunate artists to help themselves from – although when I asked John about it he explained, “They were coppers”.’ The meagreness of this largesse indicates the low levels of local artistic aspiration.

The best of British artists instinctively looked to France for inspiration and fresh directions. Walter Sickert, who died in January 1942, just as Freud and Craxton were moving into Abercorn Place, was one of the most talented and serious painters at work in London in the first half of the twentieth century. Yet he always felt that the ‘genius of painting hovers over Paris, and must be wooed on the banks of the Seine’. Accordingly, he spent lengthy periods on the other side of the Channel. Essentially Sickert was correct. In the 1930s and 1940s, Frank Auerbach recalls, ‘people in Paris had the intellectual energy, the standards and the industry’. Artistically, London had long been a backwater, even before the war.

If simply being a painter seemed strange to the people Freud met at parties, being a Modernist would have been doubly incomprehensible. Puzzlement and incredulity were certainly the reactions of the character played by George Formby in Much Too Shy, a film from 1942 in which the comedian and singer played an aspiring commercial illustrator. In one scene he stumbles into a ‘School of Modern Art’ where various students are producing work of a Surrealist nature. ‘Where’s his arms and legs?’ he exclaims in comic bewilderment on seeing one particular picture. ‘Oh,’ a painter played camply by Charles Hawtrey explains, ‘we abstract.’

By a strange chance, Much Too Shy was one of a couple of films in which Freud got work as an extra, playing the part of an art student. Meanwhile, in real life, Peter Watson had sent the two young artists off to life-drawing classes at Goldsmiths’ College in South London to sharpen up their skills (Craxton felt his own drawing was ‘chaotic’ and Lucian’s, at that stage, just ‘very bad’). Freud, indeed, considered he had an ‘almost total lack of natural talent’. His early drawings, nonetheless, had energy and – what many artists never achieve – an individual line. He aimed to discipline this by observation and by drawing constantly. Graphic art, at this stage, seemed much more feasible than painting, which he felt he could not control at all.

The classes Freud and Craxton attended were conducted on more traditional lines than those in the ‘School of Modern Art’ in Much Too Shy and their unconventional efforts attracted some critical attention, as recalled by Craxton:

We both decided, probably because of Picasso, that we were just going to put one line down. The common way of drawing was to stroke the side of the nude with about twenty-five lines; your eye picked out the one that was the right one. We thought that was a cop-out, so we sat down to do absolutely one-line drawings of all the nudes. Shading was done with dots, so of course we got lots of remarks like, ‘How’s the measles?’

*

The social world that Freud and Craxton inhabited was intimate, in that almost everyone knew everybody else. It was crisscrossed by complex amorous relationships that took little account of gender or marital status. This was a district of London’s bohemia, which was – as David Hockney has noted – ‘a tolerant place’. Attitudes were prevalent there, in the mid-twentieth century, which did not reach the wider population for another fifty years. In its acceptance of idiosyncrasy and excess it was a microcosm of the future. Life in wartime London, Craxton remembered, was ‘like scrambling up a crevice – everything was narrowed down to practically nothing. Everyone went slightly mad with the bombs.’ He and Freud would bicycle down from Abercorn Place to Soho, where much of what remained of London’s literary and artistic population would gather, and every night there was a hectic, spontaneous party:

Soho was very useful during the war if you wanted to have an existence; it had an element of danger, which was nice. It was where you ran into all your friends; there was a conspiracy to go drinking together. And they were all drinking hard – as you were yourself. All I can remember about Dylan Thomas is this swaying figure with pints of beer in his hand. But they were all swaying. Colquhoun and [Robert] MacBryde went on a sort of pub tour up into Fitzrovia. But on the whole, Lucian and Dylan and I stuck to Soho.

Known as ‘the two Roberts’, Colquhoun and MacBryde were Scottish alcoholic painters, who were effectively – though in those days, of course, not legally – married to each other and were accepted and revered despite behaviour that was, on occasion, wildly aggressive. MacBryde, on being introduced to the poet George Barker, held out his hand and crushed the glass that was in it into Barker’s palm. The poet, in response, punched MacBryde so hard on the head that he claimed he was deaf in one ear for days afterwards (the evening nonetheless ended very amicably). Craxton ‘found Colquhoun and MacBryde very good company at times, when they weren’t too drunk’. Colquhoun never hit him in the face, ‘though he did a lot of other people. They were always railing against the English, but I quite liked that, it was rather fun.’ Freud saw a more serious side to Colquhoun’s character. There was ‘something absolute’ about him, he thought. ‘He seemed very doomed and had a certain grandeur. He saw how tragic his situation was and also that it was irreversible.’

Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, c. 1953. Photo by John Deakin

The London art world was a small pool, and one that had shrunk even further since 1939. Some important figures had departed; the abstract painter Ben Nicholson and his wife, Barbara Hepworth, left with their young family for the safety of St Ives in Cornwall, never to return. Others, who will feature prominently in the pages to come, were in 1942 experiencing the varied fortun...