![]()

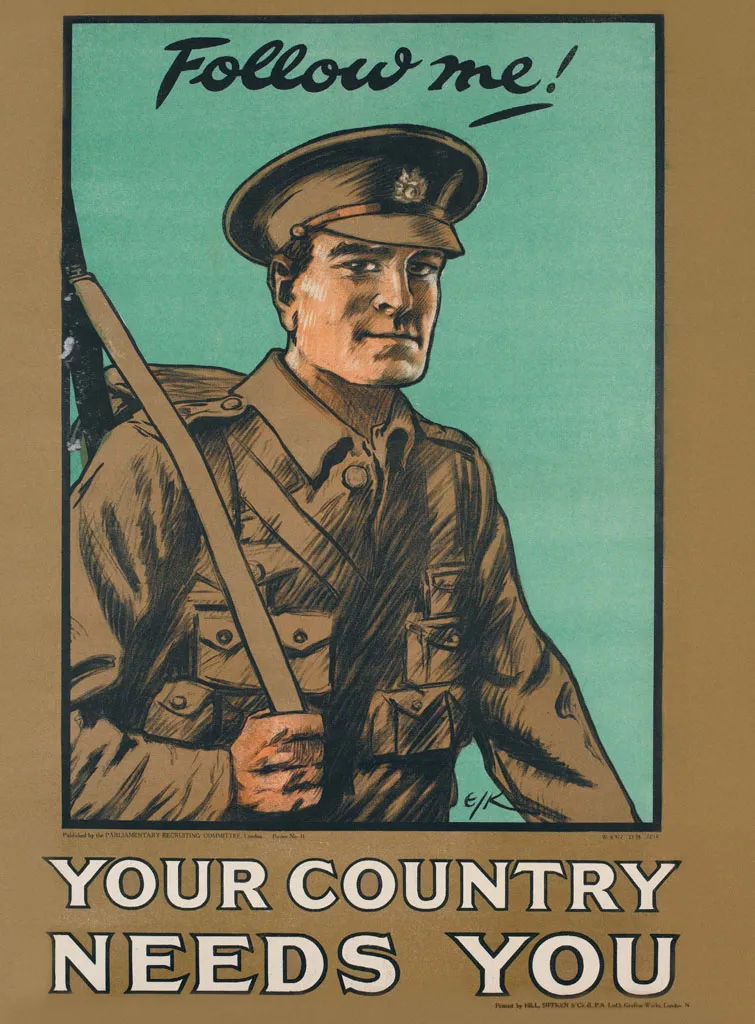

Recruitment posters such as this one encouraged huge numbers of young men to volunteer to join the forces in the early months of the First World War.

1 | THE FIRST WORLD WAR: THE FOUNDATION IS LAID 1914–1918 |

“WE STARTED A MOVEMENT WHICH MEANS THAT NO WAR CAN BE FOUGHT IN THE FUTURE WITHOUT CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION COMING UP.”

Within days of the outbreak of war in August 1914, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, initiated a major expansion of Britain’s land forces, calling for a series of ‘New Armies’ to be raised and in due course put in the field with the vast number of troops now mobilizing across Europe. Unlike the Continent’s conscripts, however, Kitchener’s men were to be volunteers, raised from thousands of young men who enthusiastically flocked to the recruitment centres, keen to join the fight before it was over. Eighteen months later, 2,675,149 Britons had volunteered. By this stage, however, the government and public had begun to appreciate just how long and costly the war was going to be. The early war of movement over open ground had given way to trench warfare and stalemate on the Western Front with no breakthrough in sight, and the total number of killed, wounded and missing passed half a million following the ill-fated Dardanelles campaign of 1915. Against this background, the number of volunteers began to decrease significantly. A form of voluntary registration was introduced by Lord Derby, director-general of recruiting, in the autumn of 1915, but it became clear that many more men were going to be required to fight the long war of attrition that lay ahead: conscription had become unavoidable.

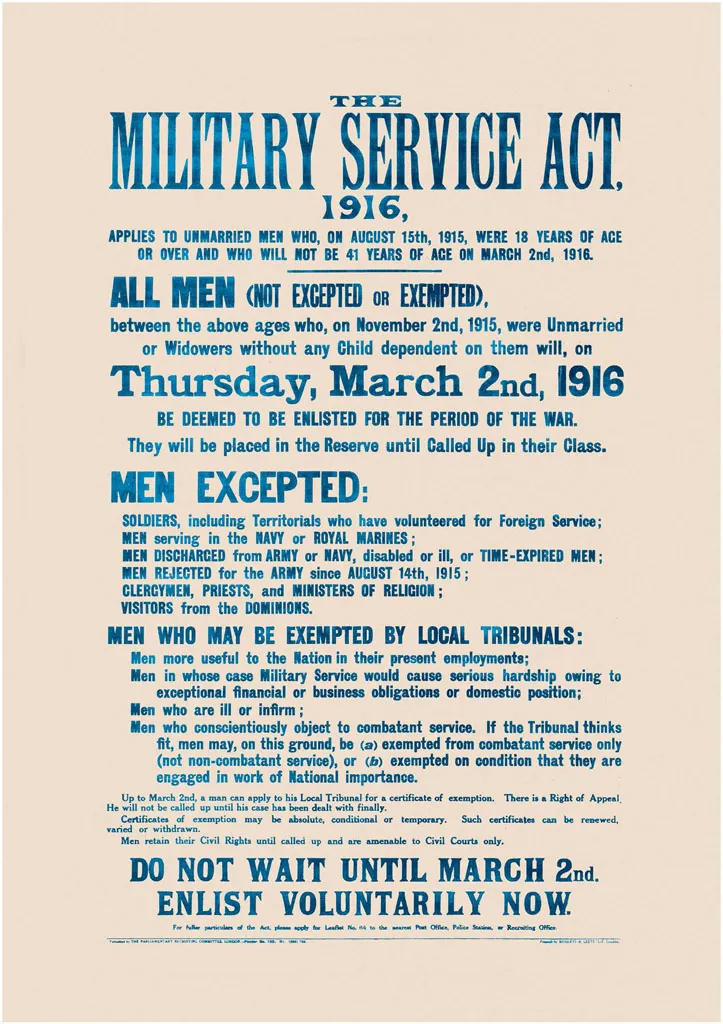

On 5 January 1916, the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, introduced a Military Service Bill to the House of Commons that established national conscription for the first time in British history. The Bill was enacted on 24 January by 383 votes to 36, after heated and bitter debate. Opposition came not only from pacifists, but also from those arguing on political, moral, legal and humanitarian grounds. By the terms of the Military Service Act, from 2 March 1916 single male citizens aged between 18 and 41 were liable for call up; after a few months the terms were extended to include married men. Exemptions, subject to appearance before a tribunal, were granted for those doing work of national importance; those whose military service would cause serious family hardship owing to financial, business or domestic obligations; those who were ill or infirm; and those with a conscientious objection to bearing arms. It was with this last category that the ‘conchies’, as they were popularly known, came into being: men who were prepared to go to great lengths to stand up for their beliefs, forming a movement that, in effect, challenged the authority of the state.

Lord Kitchener’s iconic image on recruiting posters was so ubiquitous from September 1914 that Margot Asquith, the Prime Minister’s wife, referred to the Field Marshal as ‘the poster’.

The terms pacifism and conscientious objection are often used synonymously, but there is a difference. Pacifism in its basic sense is the belief that all war and violence is wrong and should be rejected; its historical roots go back two thousand years to the teachings of Jesus Christ, with a significant more recent manifestation being the Peace Testimony of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1661. Pacifists have always been central to the anti-war movement; logically, in time of war pacifists should be conscientious objectors (COs), but not all COs need be pacifists. Non-pacifist COs may disapprove of war and realize that its prevention must always be attempted, but accept that it is sometimes necessary. Other protesters might take the view that war itself is not wrong but some part of it is unacceptable, or perhaps a particular conflict may be considered unjustified by them.

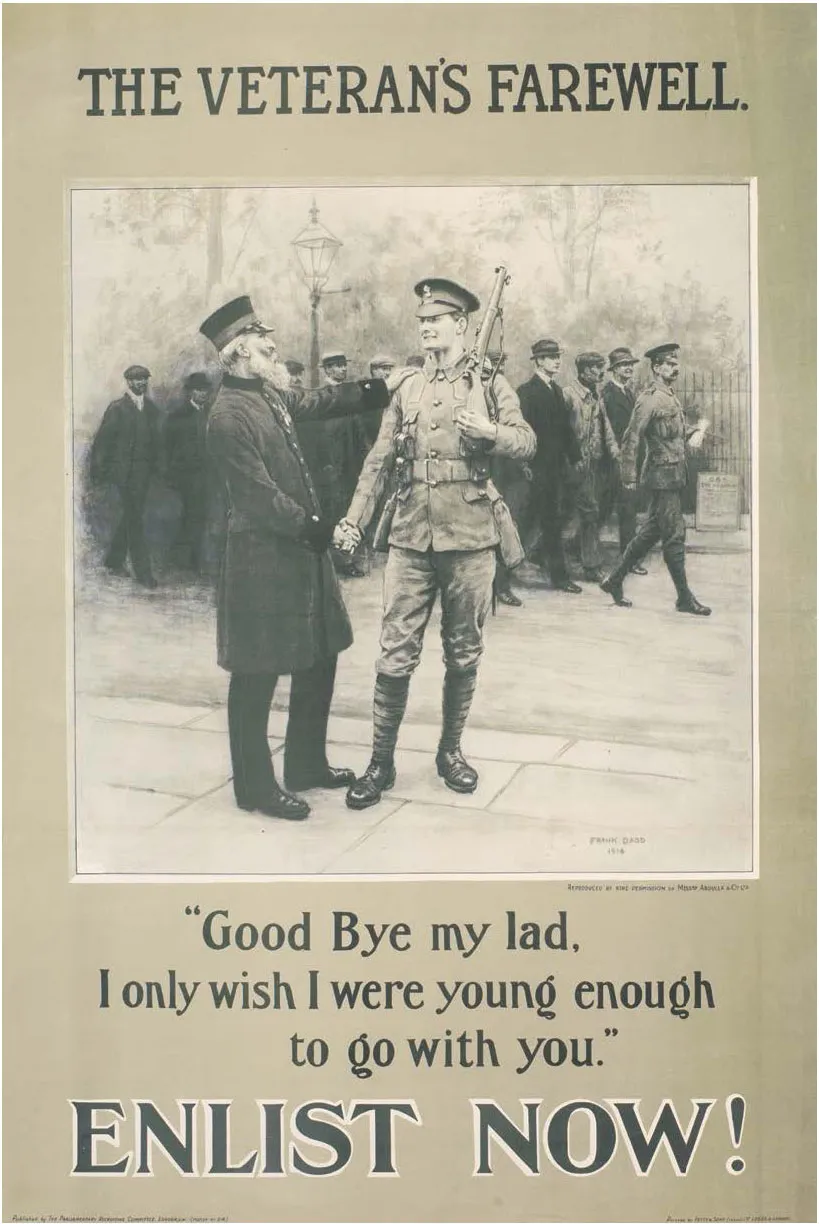

A recruitment poster depicting a veteran from an earlier war bidding farewell to a young soldier about to set off with his comrades for war with Germany.

Herbert Asquith, Liberal Prime Minister from 1908 to May 1915 and leader of the coalition government from May 1915 to December 1916, when he was replaced by David Lloyd George.

David Lloyd George, Minister of Munitions, 1915–16, giving a rousing speech in Dundee, Scotland. He was in favour of conscription, but also wanted skilled men to be kept working in their factories.

Conscientious objection, as with pacifism, is of a highly individual nature and COs came from different social, political and educational backgrounds; they had a variety of arguments to support the legality and morality of their objection to military service. There were socialists, who believed that the working men of the world should unite, not obey orders to kill each other; those who had religious grounds, including Christians of different denominations, Muggletonians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Plymouth Brethren, Quakers, Christadelphians; and members of intellectual coteries such as the Bloomsbury Group, who believed that the war was a fight against the militarism embodied by Germany and conscription made Britain no better than its enemy. There were great differences in the way these individuals and groups reacted to the war and how much compromise they were prepared to make. Given the sheer complexity of the issue, it is no wonder that the tribunals, when attempting to test the sincerity of would-be COs, found the task so daunting.

A poster detailing who could be called up and who was exempted under the terms of the Military Service Act of 1916.

The Labour Party, the most internationally minded of the political parties, opposed the war in principle, but once hostilities started divisions emerged, with many members swept along by the patriotic fervour of the time. The German invasion of Belgium on 4 August 1914, as well as providing justification for the altered stance towards the war, led to a change in the leadership of the party. Ramsay MacDonald, a notable anti-war campaigner, resigned as leader when the party voted to support the government’s request for war credits of £100 million. He was replaced by Arthur Henderson who, although he had co-signed an appeal to the British people on behalf of the International Socialist Bureau on 1 August that said ‘Down with war’, declared that his main concern once the conflict had started was national unity and safety. Henderson became the main figure of authority within the party and when Asquith formed a coalition government in May 1915, bringing in Opposition figures, Henderson became the first Labour politician to be made a member of the Cabinet.

Young men entering the No-Conscription Fellowship’s second national convention in April 1916. One of them clearly shows his objection to military service.

Rifts in the Labour movement were also manifest in the different stances of the Labour group in Parliament, the Labour Party, which had been founded in 1906, and the Independent Labour Party (ILP), a socialist party established in 1893, which had some 30,000 members by 1914. With its ethically based objection to war and militarism, the ILP steadfastly refused to support the conflict; Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, both leading members of the ILP, continued to speak passionately against it.

The Union of Democratic Control (UDC), a non-partisan pressure group that was concerned about the lack of democratic accountability in the making of British foreign policy, was founded in September 1914 by a number of well-known MPs, including Ramsay MacDonald, Charles Trevelyan and Arthur Ponsonby, and journalists such as Norman Angell and E. D. Morel. Under their guidance, the UDC focused its campaign on the causes of war and on preventing another. It sought to obtain a full examination of the war aims both in Parliament and among the wider public and it also opposed conscription, censorship and other wartime restrictions on civil liberties, which had been imposed under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), enacted on 8 August 1914. The Quakers were strong supporters of the UDC and many members of the women’s suffrage movement, such as Helena Swanwick and Florence Lockwood, forged close links with the Union. Towards the end of the war the UDC had 10,000 members in over one hundred branches across Britain and Ireland.

The Daily Mirror, 18 July 1916, announces the surrender of the leadership of the No-Conscription Fellowship to the police to face the consequences of their peace activities. Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway are on the extreme right, marked by the letters D and E.

In November 1914, with the prospect of conscription on the horizon, a group of pacifists set up the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF); this organization was to prove of immense benefit to COs and their families. Fenner Brockway, the editor of the anti-war ILP newspaper Labour Leader, credited his wife, Lilla, with the idea that those who would refuse military service should get together. Brockway became the honorary secretary and Clifford Allen its chairman. Membership was open to men of all political and religious opinions liable for call up who would refuse to bear arms for conscientious reasons. Most of those who joined were of military age and many were Quakers or other religious pacifists. Two-thirds of the membership belonged to the ILP. As Brockway later explained, ‘I wouldn’t say that we had any common philosophy then… But the statement of principles, which those who joined the No-Conscription Fellowship signed, spoke of the sanctity of human life, and its essence was pacifist.’

Once conscription started, the NCF developed into one of the most efficient and effective organizations the British peace movement has ever had. This was underlined by an impressive intelligence service that helped provide information for the records department established by Catherine Marshall, a militant suffragette. As well as keeping track of those who were arrested and imprisoned, the NCF advised men on how to present their cases at tribunals and monitored these. A visitation department w...