![]()

THE NORSE DIVINITIES

There are two distinct groups of Norse gods, the majority Æsir and the altogether more mysterious Vanir. Both tribes have male and female members, but although the female Æsir are known as Ásynjur (goddesses), the Vanir don’t seem to have a separate term for their females, perhaps because Freyja is the only one we know about. Æsir is the plural of the noun Áss, meaning ‘god’; when the term is used by itself as ‘the Áss’, it usually refers to Þórr.

THE ÆSIR

Óðinn, whose name means something like ‘the Furious One’, is the leader of the gods; he is sometimes called the ‘All-father’, but it is not a name that crops up often. He’s a war-god, but unlike Freyr, he’s more of a strategist than a fighter, teaching his chosen heroes effective battle-formations, including one shaped like a pig’s snout, the svínfylking. Óðinn stirs up conflict, so that he may see who is worthy to enter his great hall Valhöll (Valhalla), to join the Einherjar, the warriors who will fight with the gods at ragnarök. He decrees defeat or victory in battle, and he is able to confer immunity to wounds with his spear, although he sometimes sends his valkyries to determine who will win or lose.

Óðinn

• Leader of the Æsir. One-eyed, bearded, old.

• God of wisdom, magic, battle, kingship; worshipped by the elite; chooser of the slain.

• Attribute: spear called Gungnir.

• Halls: chiefly Valhöll (Valhalla, Hall of the Slain), but a number of others, including Glaðheimr (Glad-home) and Valaskjálf (Shelf of the Slain) where Hliðskjálf (Opening-shelf), the high seat which lets him look out over the worlds, is situated.

• Transport: by eight-legged horse Sleipnir, but often travels on foot and in disguise.

• Animal associations: ravens (Huginn and Muninn, ‘Thought’ and ‘Memory’); wolves (Geri and Freki, ‘Ravener’ and ‘Devourer’).

• Married to Frigg; numerous liaisons with giantesses and human women. Sons are Þórr, Baldr, Víðarr, Váli, Höðr.

• Particularly important in Denmark.

One-eyed Óðinn with his ravens and his spear Gungnir, in an eighteenth-century Icelandic manuscript.

Óðinn is also the god of wisdom, and he seeks it out wherever it may be found. He has sacrificed one of his eyes in Mímir’s Well to gain arcane knowledge, and he hanged himself on the World-Tree Yggdrasill in order to win knowledge of the runes, the Germanic writing system which enabled gods and men to record their knowledge for posterity.

Valkyries

Valkyries are supernatural women who dwell in Valhöll. They serve wine and mead to the warriors who live there. Another of their tasks is to ride out to battle, where they bestow victory or defeat, and their name means ‘Choosers of the Slain’. Sometimes Óðinn instructs them as to who is to win, and sometimes they take the initiative in choosing who will accompany them back to Valhöll. Not all kings are thrilled to be invited to join the elite (but dead) warriors, rather than continuing to rule on earth. A memorial poem for the Norwegian King Hákon depicts him as distinctly sulky, even when the greatest heroes of the past welcome him to the hall. The valkyrie Brynhildr is punished by Óðinn for disobeying orders and giving victory to a younger and handsomer man. Some human girls also take up the valkyrie life as shield-maidens. This allows them to choose a heroic husband who can save them from marriage to an unwanted suitor, as we’ll see in Chapter 4.

A valkyrie in full flight, sculpted by Stephan Sinding (1910).

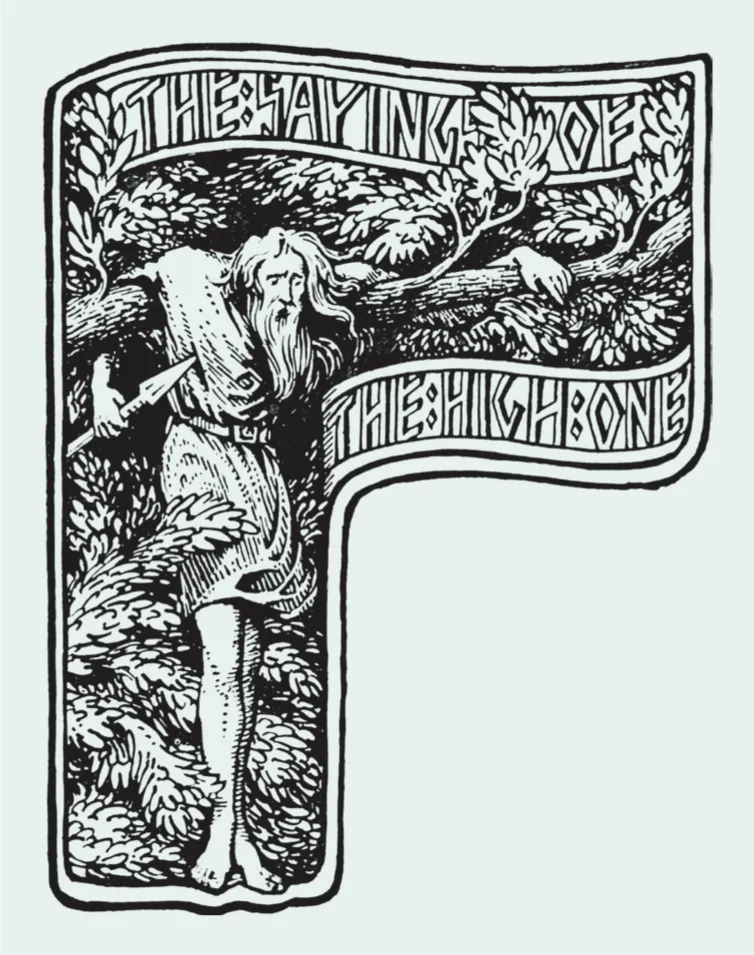

Óðinn hanging himself on Yggdrasill. Illustration by W. G. Collingwood for Olive Bray’s 1908 translation of the Poetic Edda.

I know that I hung on a windswept tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Óðinn,

myself to myself

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.

With no bread did they refresh me nor a drink from a horn,

downwards I peered;

I took up the runes, screaming I took them,

then I fell back from there.

SAYINGS OF THE HIGH ONE, VV. 138–39

Óðinn also knows spells to achieve various things: animating the dead, quenching fires, calling up winds. He lists eighteen of them in Hávamál (Sayings of the High One), but declines either to give details or to reveal the last one, which he won’t tell any woman, unless it’s his lover or his sister – and since there’s no evidence for him having a sister, and he doesn’t necessarily part on good terms with his lovers, that secret may be kept for a very long time indeed.

One of Óðinn’s chief concerns is to find out as much as he can about ragnarök, the end of the world. To this end he visits various people in the divine and human worlds (see Chapters 5 and 6). He knows that the death of his son Baldr is one of the most significant portents of the end, but he hopes that – somehow – he can find a way of falsifying the prophecies about the catastrophe to come. He is also an accomplished practitioner of magic of a particularly disreputable kind called seiðr (see Chapter 2, page 84). We don’t know much about what this entails, but it seems mainly to be the province of women. When men perform it, it involves cross-dressing: something that is inherently shameful in Norse culture. In fact, Óðinn and Loki have an exchange of words about it in the poem Lokasenna (Loki’s Quarrel). When Óðinn accuses Loki of spending eight winters under the earth in the form of a milch-cow and a woman, bearing children there, Loki retorts that his blood-brother ...