![]()

1 Pictures and Reality

All pictures are made from a particular point of view.

DH - Two dimensions don’t really exist in nature. A surface only looks two dimensional because of our scale. If you were a little fly, a canvas or even a piece of paper would seem quite irregular, whereas to us, some things can be seen as flat. What’s really flat in nature? Nothing. So the flatness of a picture is a bit of an abstraction. However, it is an abstraction that has consequences. Everything on a flat surface is stylized, including the photograph. Some people think the photograph is reality; they don’t realize that it’s just another form of depiction.

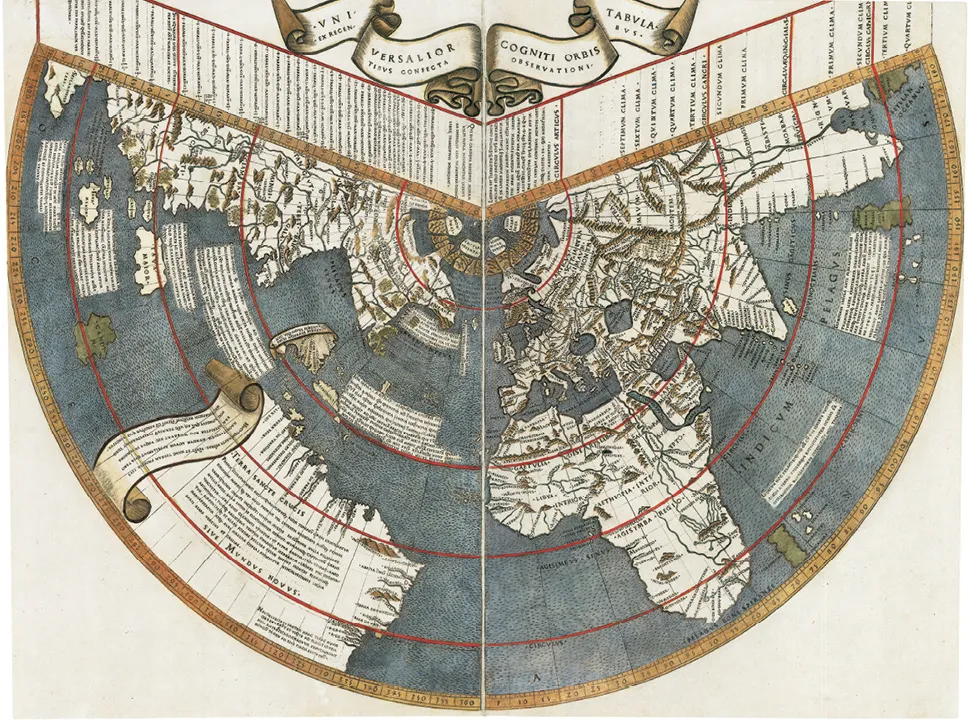

MG - It is the essence of a picture that it is two dimensional, but attempts to represent three dimensions. In that respect a picture can be compared to a map. Indeed, a map is a highly specialized type of picture. The task of a map-maker is to describe the features of a curved object – the Earth – on a flat one. To do so with complete fidelity, as was demonstrated long ago, is a geometric impossibility. Therefore, all maps are flawed and partial, and reflect the interests and knowledge of the person who made them. The situation is analogous with that of pictures. They are all attempts to solve the same problems, to which a perfect solution is impossible. The imperfect solutions are infinite, however. Each attempt has its own virtues and drawbacks.

Like many medieval images of the world, a map made by a Venetian monk, Fra Mauro, in the mid-fifteenth century, places Jerusalem near the centre, the point from which all history was thought to radiate. Fifty years later, a map drawn by Johannes Ruysch in 1507 depicts an expanded view to include some of the discoveries made by Portuguese and Spanish explorers. It projects the world in the way the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemy had suggested, as it would be if one cut a paper cone open and pressed it down on a table. However, the world is not a cone.

FRA MAURO

World map, c. 1450

Vellum

The map is shown with south at the top

JOHANNES RUYSCH

Map of the world, 1507

Engraving

Every map is made from a certain angle of vision. The ones we have been discussing were drawn from a European vantage point. The 15th-century Korean Kangnido map, one of the oldest surviving maps from East Asia, quite reasonably looks at the world in a different manner, one in which China and Korea bulk large, and Europe, the Middle East and Africa are crammed into the margin.

DH - All pictures are like that; they are made from a particular point of view. We all see the world in our own way. Even if we are looking at a small square object, a box say, some of us will see it differently from others. When we go into a room we notice things according to our own feelings, memories and interests. An alcoholic will spot the bottle of whisky first, then maybe the glass and the table. Someone else notices the piano; a third person sees the picture on the wall before anything else. Reality is a slippery concept, because it is not separate from us. Reality is in our minds.

YI HOE and KWON KUN

Kangnido map (detail), c. 1470

Paint on silk

So you ask yourself, what is it you are getting in the picture? In Egyptian art the biggest figure is the pharaoh. Well, if you had measured him in real life he might have turned out to be the same size as anyone else, but in Egyptians’ minds he was bigger, so that is how he was painted. That seems to me a perfectly correct way to proceed. The realist way would be to paint him small.

All writing is fiction in some way, how can it not be? The same is true of pictures. None of them simply presents reality.

MG - In his pictures of the floating world (Ukiyo-e) the Japanese print-maker and painter Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753–1806) drew elegantly willowy women. However, the first photographs of Japanese courtesans, taken in the late 19th century, show women who were maybe less than five feet tall.

DH - But in Utamaro’s time they would have seen them as taller! It was only the photograph that made them look squat. Even in their minds they wouldn’t have looked like that. Is that what the photograph has done to us? It’s made the world look duller? I believe the photograph does that, because it is separate from us. The camera sees geometrically but we see psychologically.

Ramses II on a Nubian military expedition, plaster cast of wall painting at Temple of Beit el-Wali, Aswan, Egypt, 13th century BC

I think, in the end, it’s pictures that make us see things. We need pictures; we need them in our imaginations, but first you have to have something down on a surface. Pictures have been helping us see for at least 30,000 years.

MG - Picasso is supposed to have suggested art had been decadent since the era of Altamira, the painted cave in northern Spain. And in many ways it’s true that painting remains what it was there and at Lascaux.

DH - Art doesn’t progress. Some of the best pictures were the first ones. An individual artist might develop because life does. But art itself doesn’t. That’s why the idea of the primitive is wrong, because it assumes that art is a progression. Vasari in his Lives of the Artists in the mid-16th century thought Giotto came first and it all finished with Raphael and Michelangelo. Nothing could be better than that. But Raphael isn’t better than Giotto.

The people in Giotto’s fresco are individuals. I know these faces. They are types, in a way, not studied from actual people, but they have lively expressions, they have personality. The eyes particularly have an intensity of looking. When the whole Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, painted by Giotto, was first done it would have seemed like vivid reality, something far more powerful than film or television. It still is an amazing building.

DH - One of my ancestors was probably a cave artist. I think cave art must have been to do with someone getting a piece of chalk or something and drawing an animal. Another person sees it and perhaps gestures or reacts, meaning, ‘I’ve seen something like that!’

Once I was in Mexico working on ‘Hockney Paints the Stage’. We’d decided to do a roll of people who were at the opera...