![]()

Chapter 1: Introduction

In theory, artists can depict anything they wish, but they don’t. Claire Smith, former President of the World Archaeological Congress1

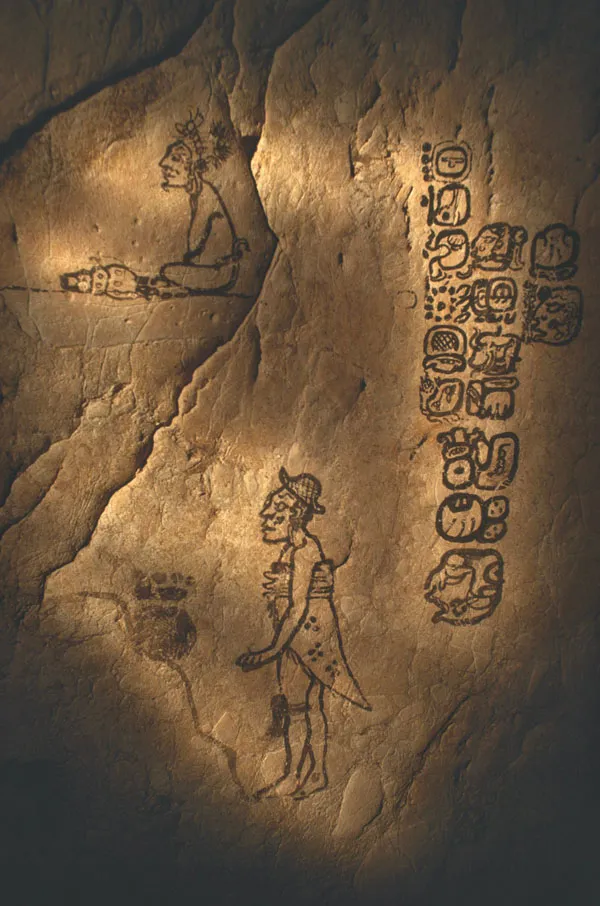

In 1979 a remarkable discovery deep in the jungles of Guatemala revealed to the world a hitherto unknown underground realm of Maya art. The cave of Naj Tunich [2], in use during the first millennium AD, enticed professional archaeologists and the public alike to imagine a new kind of ancient Maya pilgrimage across cosmic layers beneath an emerald green rainforest roof. Amid hanging stalactites and cavernous passageways, stone altars, smashed ceramic vessels, glyphic inscriptions and curvilinear drawings of women, men and sacred beings in distinctive, contemplative Maya pose [3] gave testimony to a sacred landscape that had remained preserved for centuries. Maya ethnography and ancient writings enabled the art and rituals to be deciphered, a knowledge to which we will return in the final chapter of this book.

2. Entrance to the cave of Naj Tunich, Guatemala, where a previously unknown subterranean world of Maya art and religious performance was rediscovered in 1979.

3. Maya art on the cave wall at Naj Tunich, Guatemala. Both the script and the identity of many of the personages in the art were worked out from Maya texts and ethnography (discussed in Chapter 7).

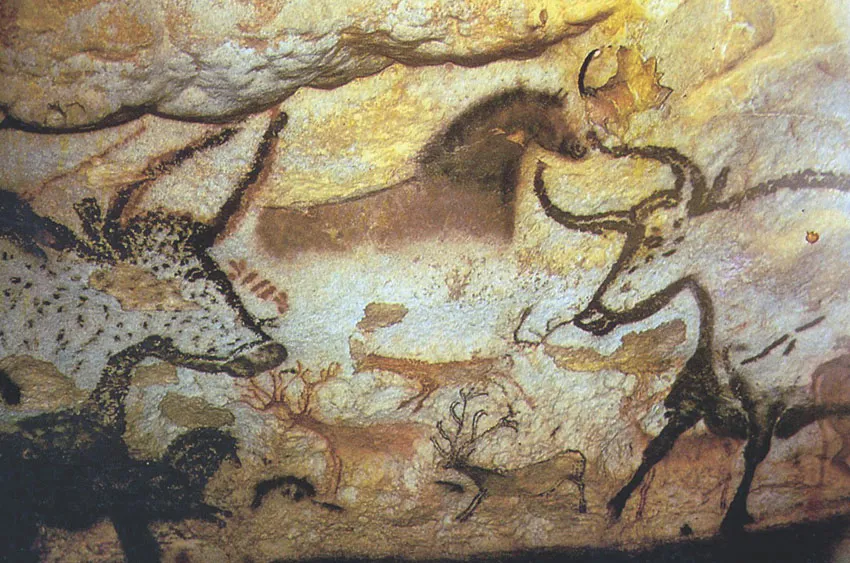

In that same year, on the other side of the Atlantic, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) added a number of well-known French Ice Age caves richly decorated with rock art dating back some 12,000 years and more to its World Heritage List. Among these was the crowning jewel of the French Upper Palaeolithic, the cave of Lascaux with its ochre red, yellow and black pantheon of painted bulls, horses and other creatures [4]. But unlike Naj Tunich, those French sites had no ethnography of any kind, no way of making sense of what the art meant to people so many thousands of years ago.

4. Upper Palaeolithic paintings dating to the Ice Age in the Hall of Bulls, Lascaux, France.

After decades of enquiry, sometimes with considerable insights, we continue to ask: who made these fantastic paintings, deeply buried in the hollows of the earth, and why? The artists of Naj Tunich and Lascaux belonged to very different worlds and very different times, and they came from cultures utterly unlike our own. Understanding their artwork thus necessitates understanding not just the artists as individuals who painted, but also the cultures from which they came. While to some degree the works of art can be seen as the creations of individual artists, they cannot be reduced to the genius of entirely free minds, of blank slates, because how people choose to do things is to some degree conditioned by their cultural traditions. Furthermore, while an artist can decide to make or do something, the end product is rarely exactly what was anticipated at the start of the work. What we see in the art that adorns the cave walls of Naj Tunich and Lascaux, as with cave art all over the world, is as much the product of subliminal cultural forces that shaped how people once saw the world as it is the intentions of individual artists. And what we see in those caves also reflects how we ourselves, as observers, have been conditioned to see.

Many theories have been developed over the past 150 years to explain cave art. These have tended to be Grand Theories that tried to make sense of the art by reference to a single, overarching logic. Back in the nineteenth century, when cave art first began to be rediscovered in Spain and France, it was generally thought that the art was made for its own sake – ‘art for art’s sake’ – as presumably ancient humans were too ‘primitive’ for higher kinds of reason. Then notions of totemism and ‘hunting magic’ became prevalent, as the world views and religious practices of living Indigenous peoples came to be documented, those new inspirations being applied to the art of Ice Age Europe. But as Indigenous communities continue to remind us today, their cultures, their artistic practices, relate to their own ways of doing things, to their own, very particular histories, not to that of others with whom they have never had any direct or even indirect contact in other parts of the world (see Chapter 7). A few decades later, these and other similar ideas were again replaced, this time by ideas of ‘binary art’ structured across cave walls, the assemblage of motifs signalling the unity of opposites, ‘male–female’ and the like. From this emerged complex notions of semiotic structure that viewed artworks as ‘signs’ arranged in complex but preformulated ensembles which, once understood, would reveal the meaningful ‘language’ of the art. More recently, there has been a swell in interest in some parts of the world, and by some researchers, in notions of ‘shamanism’, with all kinds of sites, cultures and artworks (other than our own!), of the past and present, being interpreted as the art of ‘shamans’. These latter notions were first developed in the 1980s, in the shadow of dissatisfaction with the mechanistic interpretations of the 1970s that saw human behaviour as the product of universal laws of survival and biological reproduction, so that life (and human achievement) was usually written about in English-language science books as little more than a quest for food and survival. The 1980s rejuvenated a sense for the intangibles of life in science, reminding us that what makes existence meaningful among the world’s varied cultures relates to such things as spirituality, human care, the mysteries of life and death, the emotions of everyday life, and how we make sense of and appreciate things. Interpretations of cave art thus began to search for ways to incorporate such issues, and to make them centre-stage of scientific explanations, rather than to relegate them to the edges of what really matters, more or less meaningless epiphenomena, as the 1970s had done. Yet the new explanations again came to marginalize peoples, cultures and ways of being, and as much so as the earlier Grand Theories had done, for these new explanations were also Grand Theories that paid no real attention to the reasons why particular cultures had made art in the distant past, or, in the case of most Indigenous groups across the world, why they made art recently or continue to do so today. They did not give voice to the practices and motivations of the very people who had made the art, where this was known. This is often the fate of Grand Theories that do not address or neatly fit into the ways of all.

This book takes a different tack: rather than applying an overarching explanatory framework to cave art, a Grand Theory, I am more interested in what happened in the past as a way of approaching why when dealing with decorated caves. How do we know how to make sense of such arts? I am more concerned with particularities than with overarching explanations. And I am more interested in understanding how we can be sure of our knowledge, rather than masking that knowledge with the veil of a Grand Theory. Sometimes, where artists or members of their communities can speak and explain the cultural contexts of the art for themselves, we can listen, and we can hear aspects of knowledge that we would not otherwise know about (see Chapter 7). This may not be the only story to tell – I make more of this below – but it is an important one.

Tracking history through cave art

Archaeologists are interested in understanding the past by tracking cultural practices from the depths of history: we use carbon dating to find out how old things are, space-age digital technologies to once again see colours that had, for all intents and purposes, completely disappeared from cave walls, and record traditions from Indigenous elders to try to connect artworks made by the ancestors with ideas expressed in more recent cultural perspectives (see Chapter 3). In doing so, we are also interested in understanding how the present came to be as it is today, both in our own cultures and in those of others. We do this by accessing two major sources of information: one, by understanding as much as possible the present cultures whose history we try to track, for example via discussions with community members and through the writings of anthropologists; and two, by studying the material remains of past human actions, to see what archaeological finds such as portable artifacts, ancient camp sites, artworks and the like can reveal about what people did in the past. These two sources of information allow for a ‘two-way’ historical investigation: tracking present cultural practices back in time to try to determine their origins, and following ancient practices forward in time to see how they have developed.2

Rock art specialists Paul Taçon and Christopher Chippindale have aptly pointed out that this double approach to historical research can employ two kinds of enquiry, ‘informed’ and ‘formal’.3 Informed research refers to evidence gathered from people who have first-hand knowledge about the topic of interest, for instance artists who can reveal information about their works, or community elders who can illuminate the cultural conventions under which artworks were produced. Such an approach is useful at Naj Tunich, where Maya culture and ancient texts can help us understand the art in the cave. But it is of no use for Lascaux and other Ice Age caves, so here we resort to formal research, where a broad spectrum of technical methods can be employed to study the paintings, such as carbon dating to determine their age, proton-induced X-ray emissions to study their elemental composition, or multivariate statistics to discover structural patterns among motif types – how different kinds of images may be associated with each other. For many images and sites, informed and formal research is done hand-in-hand, but this is only possible where the cultures that produced the art live on, or have been recorded in documents and oral traditions.

For many recently rediscovered ancient sites we must rely on formal methods, on the way that images can inspire us to think in certain ways, and on the genius of innovative researchers who find ways of shedding light on the distant past. Those researchers are readers of the art that has been left behind, those visual cues in many ways presenting themselves like graphic ‘texts’ made of strange, unknown signs. The images were made in the conventions of the day, and in the context of, for example, the use of particular paint recipes and colours, patterns of linework, positioning of particular images in particular locations, and associations between types of motifs. But do we really know how to ‘read’ those texts, given that the cultures that produced them were likely to be so different from our own? The aim of informed and formal methods is to work out elements and structures of the artworks, to try to make sense of the cultures and intentions of the people who made them. Given that they are not the products of culture-less artists, but on the contrary creations given shape by people who found meaning in their culture, can we ever make sense of the artworks? The difficulty, as Umberto Eco has noted,4 is that while we may know the intention of the reader, of the analyst, can we know the intention of the text, of the artworks that confront us? This is the challenge of the archaeology of cave art, explored in this book by examining how sense has been made of the cave art of other cultures, often of the distant past.

While this book focuses on the archaeology of cave art, there are other ways of looking at the subject. For many Indigenous peoples around the world, what is of greater interest about the cave art of their communities is how it expresses the cosmology and realities of their own world views, how it expresses a sense of their own history, and how this ‘art’ lives on in the present. In doing so the art connects the living with the ancestors who shaped the world in which we now live.5 For example, the spirit mimi, who can be seen on the rock at Nawarla Gabarnmang in Jawoyn Aboriginal Country, northern Australia, look after ‘Country’ (further discussed in Chapter 7), and while they can be deeply felt as ancestral presences, other than in the art they remain unseen [5]. Here there is a focus on what the art means to the community of culture in which it is situated. These meanings express the power of the image and of the spirit-beings that the art embodies. In such cosmological understandings, artworks mediate the human world with that of the spirit world, because it is the ancestral spirits that have metamorphosized into the rock and are now visible as ar...