- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Is Medicine Still Good For Us?

About this book

Modern medicine is exceptionally powerful, and has achieved unprecedented successes. But it comes at a price; individuals suffer from medicines failures, and the economic costs of medicine are now stratospheric. Have we got the balance wrong? Is Medicine Still Good For Us? sets out the facts about our medical establishments in a clear, engaging style, interrogating the ethics of modern practices and the impact they have on all our lives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Is Medicine Still Good For Us? by Julian Sheather,Matthew Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medicine1. The Development of Medicine

For most of its history, Western medicine has been almost entirely useless – its cures and remedies, cuppings and bleedings, and simples and poultices ineffective or positively hazardous.

Hippocrates is the undisputed father of Western medicine, and the Hippocratic oath may be the best-known medical text in the West. Allegedly, it is still sworn on graduation at some medical schools, although presumably adapted: in some translations, it contains an injunction to refrain from seducing slaves in the houses of the sick.

Hippocrates (c. 460– c. 375 BCE) Undoubtedly the father of Western medicine, he practised on the island of Cos, off what is now the Turkish coast. Although it is uncertain whether he wrote all the works ascribed to him, the collection known as the Corpus Hippocraticum was enormously influential in the West for nearly two millennia.

AThis 11th-century English miniature depicts an operation to remove haemorrhoids (right). A patient with gout is treated with cutting and burning of the feet (left).

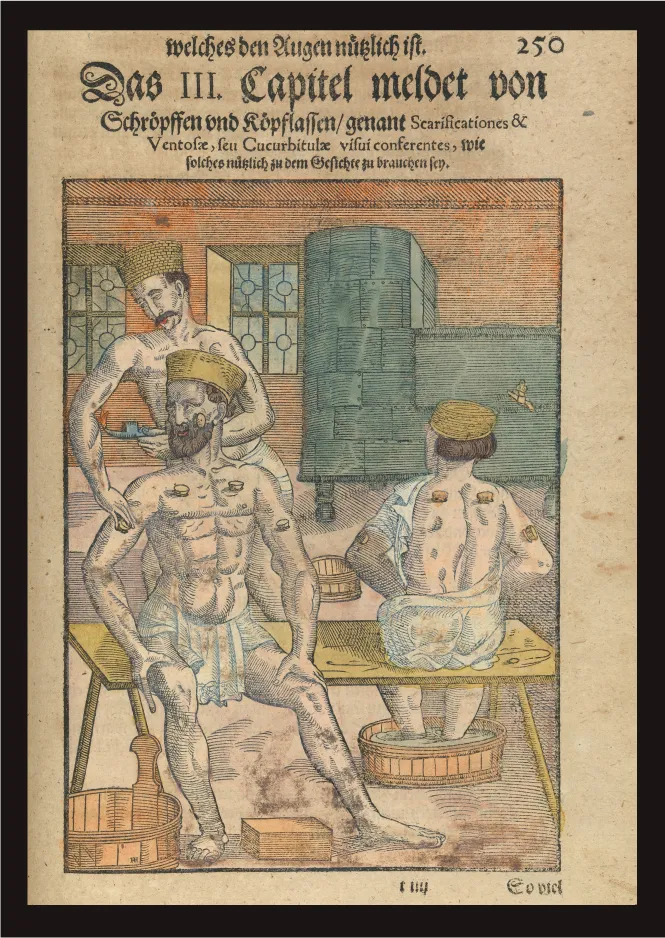

BAlthough often dramatic, many early medical interventions were almost entirely useless, such as this cupping therapy seen in Ophthalmodouleia by Georg Bartisch (1583).

CA medical staple for centuries, bloodletting was eventually shown to be ineffective. From Li Livres dou Santé by Aldobrandino of Siena (late 13th century).

Medicine, from its Hippocratic roots until the mid-19th century, was little more than a way to distract the patient while waiting to see if they recovered. According to French philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778), doctors ‘were men who put drugs of which they know little, to cure diseases of which they know less, into bodies of which they know nothing at all’. Some of this changed, and dramatically, from the mid-19th century onwards. But not all of it. As the great medical historian Roy Porter (1946–2002) wrote: ‘The prominence of medicine has lain only in small measure in its ability to make the sick well. This was always true, and remains so today.’

AIn the Corpus Hippocraticum, health was a balance of the four humours or chymoi, and poor health came from their imbalance. Here, Byrhtferth’s diagram, from a 12th-century manuscript, indicates that the humours were regarded as part of the natural order of the universe.

Hippocratic medicine was naturalistic. Unlike many of the belief systems of the ancient Near East, it did not look for the origins of disease in divine displeasure, supernatural intervention or dark magic. Health and illness were natural phenomena, amenable to observation and reason. Man was subject to the same natural laws as the rest of the universe and could be understood accordingly.

Hippocratic medicine was also holistic and patient-centred. The Hippocratic doctor needed a thorough understanding of how his patients lived and worked, what they ate and drank, what we call their ‘family history’. Healing involved careful watching and investigation of the individual patient: empiricism was stronger than theory.

Holistic Medicine that aims to treat the whole person, looking at aspects of emotional, psychological and spiritual well-being. Sometimes it is opposed to ‘allopathic’ medicine, which targets the individual disease.

Empiricism The theory that all knowledge of the world is derived from the senses. Associated with the rise of experimental science, it privileges direct experience of the world over theory or established authority.

BIn the Middle Ages, barbers did more than cut hair; they were also surgeons. As the Guild Book of the Barber Surgeons of York (1486) shows, medieval surgery combined anatomy, astrology and religion. Surgeons calculated the moon’s position before surgery.

At the centre of the Corpus Hippocraticum lies the concept of the humours or chymoi (translated as juice or sap). The humours can be thought of as the constitutive fluids of the human body – the origin of all our other fluids. On the Nature of Man (440–400 BCE, part of the Corpus Hippocraticum although usually attributed to Polybus), states: ‘The human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with others.’

Humours According to humoral theory, the human body consists of four humours – blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm. Each has its corresponding element – air, fire, earth and water – and its associated property – hot, dry, cold and wet. Each has an associated organ: blood with the heart; yellow bile with the liver; black bile with the spleen and phlegm with the brain. Each also has an associated temperament: blood makes a person sanguine or optimistic; yellow bile turns one choleric or irascible. Black bile is associated with melancholy and phlegm with imperturbability or calm.

It is likely that observing the fluids discharged during illness contributed to humoral medicine. Colds and diarrhoea saw an excessive flow from the body; fevers saw sweating and flushing. Certain illnesses brought changes to urine and faeces. Blood turned dark, almost black, when it dried. Humoral medicine offered a simple but compelling schema that was not seriously challenged until the 18th century and not replaced until the 19th.

Despite the distance in time, the paucity of Greek anatomical knowledge and the varied nature of the writings attributed to him, Hippocrates still speaks to modern disputes. His focus on the whole person, not the isolated disease or dysfunction, has seen him championed by supporters of ‘family medicine’ and by complementary and alternative therapists.

In Hippocrates, we also find the essential medical triad: the relationship between the doctor, the patient and the disease.

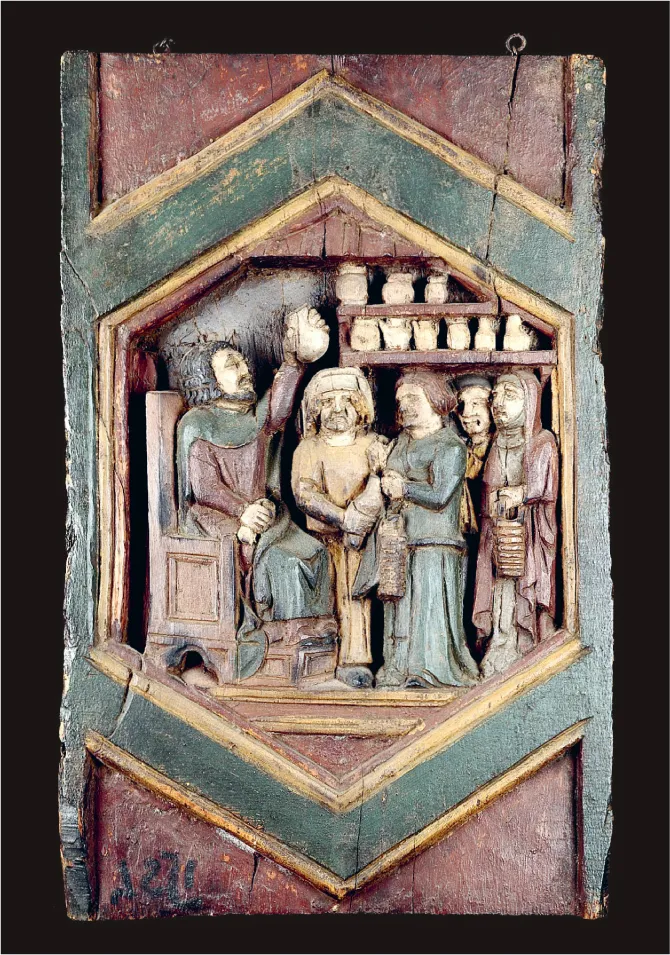

AIn this painted relief after Giotto, a medical practitioner examines urine brought by his patients. The effect of illnesses on bodily excretions, such as urine and faeces, may have contributed to the development of humoral theory.

BThis wooden statue (1770–1850) shows St Cosmas, patron saint of druggists, surgeons and dentists, performing uroscopy: studying a patient’s urine was said to provide information about the state of their humours.

CUrine wheels were used for diagnosing diseases based on the colour, smell and taste of a patient’s urine. This example, from Epiphanie Medicorum (1506) by Ullrich Pinder, was used for diagnosing metabolic diseases.

This triad remains central to medicine, but the emphasis given to each element shifts with different medical eras. Today, some find that the intense focus on disease, manifest in super-specialization (the division of body and mind into an ever-increasing proliferation of sub-specialties) dehumanizes medicine and alienates us from our own health and well-being. The concept of ‘balance’, although semantically elastic, still has its place in modern medicine: we talk of a balanced diet, of a biological system’s equilibrium or homeostasis.

The second medical colossus of the ancient world is Galen of Pergamum.

Galen of Pergamum (129–c. 216 CE) After Hippocrates, Galen is the second most important physician of the ancient world. His huge body of work systematized and popularized the Hippocratic legacy.

A Greek of the Roman Empire, Galen was a prolific and combative medical writer and philosopher. A brilliant self-publicist, and court physician to the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE), Galen was the supreme medical authority in Western medicine for more than a millennium. He systematized the Hippocratic legacy – most practitioners met Hippocrates through Galen – and added to it knowledge of anatomy and physiology, acquired through animal dissection.

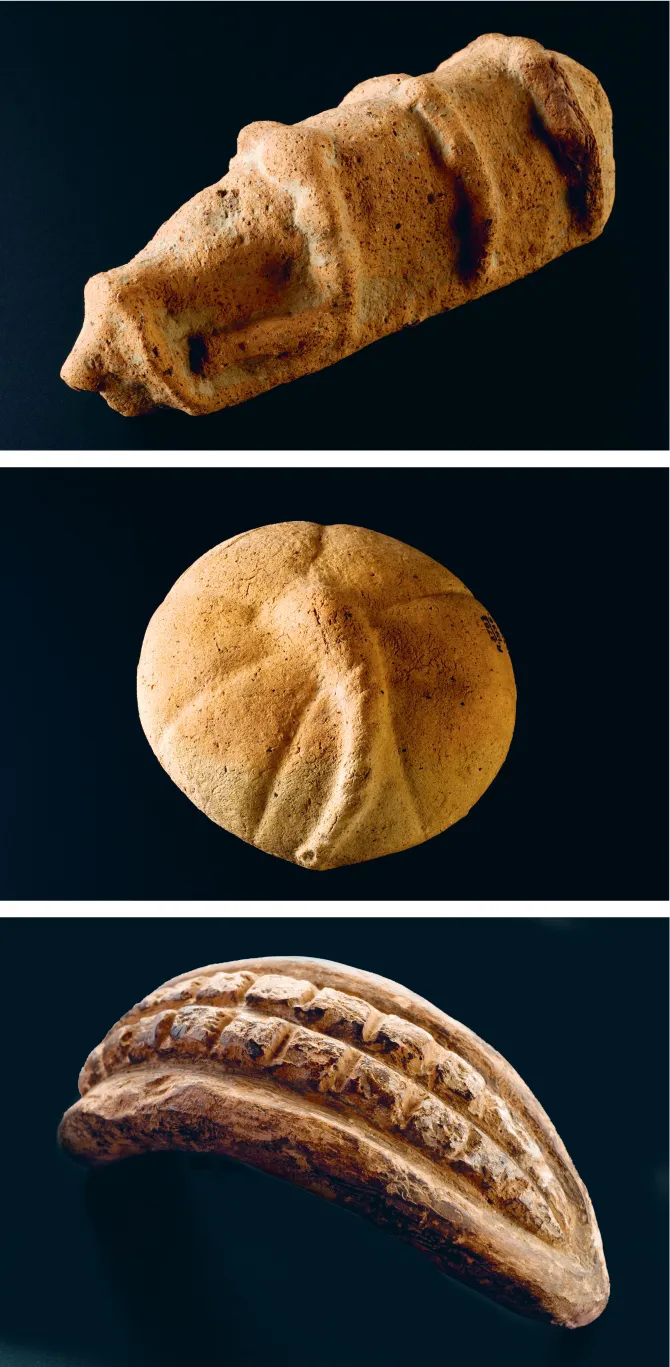

AEmpirical and religious approaches to illnesses were frequently blended in pre-Modern Europe. Roman votive offerings (top to bottom: trachea, placenta, teeth and mouth) were left at healing sanctuaries by those seeking healing from divine intervention. Usually depicting the site of illness, these naturalistic offerings were a form of sympathetic magic.

BThis display shows replicas of Roman surgical instruments. They indicate that, alongside requests for divine intervention, Roman medicine was often intensely practical.

Although the use of anatomical investigations to understand how bodies worked would have profound implications for medicine, human dissection was taboo in the a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About the authors

- Other titles of interest

- Contents

- Milestones

- How to Read

- Introduction

- 1. The Development of Medicine

- 2. How Effective is Medicine?

- 3. The Medicalization of Living and Dying

- 4. Why Modern Medicine Needs to Change

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

- Picture Credits

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright