![]()

![]()

Scene 1

A bridge

I’m walking from the west towards the historic core of the great, sprawling low-rise City of Leicester. Along this route, one day in August 1485, a king marched out to do battle; and on the next day, a new king marched in with his predecessor’s body.

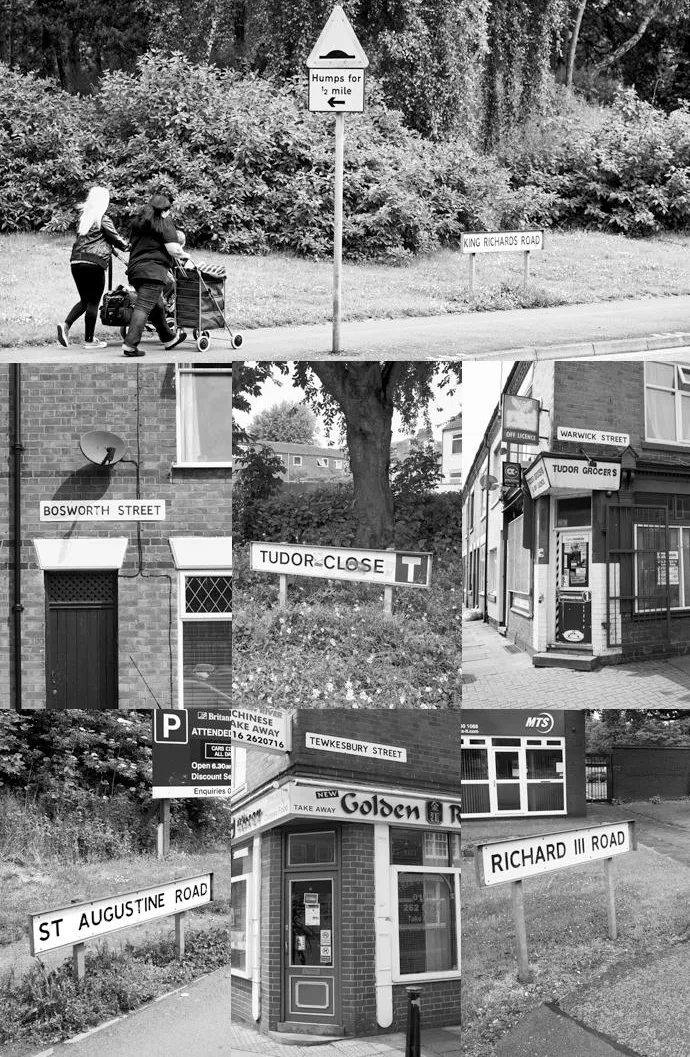

Leicester remembers the loser, which is why I am looking at a street sign that says King Richards Road. Beside it, with an arrow pointing up the quieter Tudor Road, is a warning: Humps for half mile. Even before his grave was found in a car park, Richard was truly the tarmac king.

It’s an appropriate epithet, perhaps, for a man who was celebrated in this city more by myth and legend, the common gossip of inns and news sheets, than by the grandeur of official monuments – and also for a city that, at least where I am now, is apparently defined by tarmac, by corridors of traffic that cut and divide.

When King Richard finally got a public memorial here, in 1856, it was set in a factory wall by a local builder called Benjamin Broadbent, a few hundred yards on as I stand, where the road crosses the River Soar. A willow tree had done the job for those who knew, marking the site of Richard’s grave, but it had been cut down. Mr Broadbent wanted something more permanent than a tree and more informative than a road name. The raised letters of his carved stone slab could be read as people left town over Bow Bridge or lingered at the Bow Bridge Inn opposite: ‘Near this spot lie the remains of Richard III the last of the Plantagenets 1485.’1

Since the mid-19th century, Leicester has been celebrating Richard III and the Wars of the Roses in street furniture.

Contemporary records describe how Richard was quietly buried not here, but within the city walls, in the church of Leicester Greyfriars, having first been displayed for a couple of days so the people could witness beyond doubt that the king was dead. Henry VII later paid for a monumental stone tomb. Along with everything else at the site, this seems to have disappeared when the friary was seized by Henry VIII’s accountants at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538.

Neither was Richard himself allowed to rest. According to tradition, an angry mob, at last able to get their hands on the hated tyrant, dug up his body, strode out of the city through the west gate with the decaying remains, and lobbed them into the river. There happened to be an old cemetery nearby. When the crowd had drifted away, ‘a few pitying bystanders … drew the corpse out of the water, and hastily placed it in consecrated ground’.2

Early in 1861 workmen started to take the bridge down, stone by stone, removing the very structure, it was thought, that had conveyed Richard’s army to Bosworth. It was too narrow for modern traffic, just six feet across, with little niches either side for pedestrians to dodge into as carriages passed. And, it was said, its five stone arches impeded the river’s flow after heavy rain, causing flooding.

Over the next two years the old Bow Bridge was replaced with a shiny new cast-iron structure, higher and wider and suspended over beams that completely cleared the water. Yet such progress brought a loss.

Along with the bridge, a favourite Leicester spot for recalling Richard III had been the Blue Boar Inn. The king was said to have stayed there before setting out to Bosworth. Supposedly it was then called the White Boar Inn, but was hastily rebranded when news reached Leicester of Henry’s victory – a white boar being Richard’s heraldic badge, and a blue boar, conveniently, the device of one of Henry VII’s generals. Richard’s visit not only brought fame to the hotel, but launched a small industry around the royal bed (in which the most remarkable incident was a landlady’s murder and the subsequent execution of at least one man by hanging and of a woman by fire).3

View of Bow Bridge across the River Soar, shortly before its demolition in 1861, looking west; an engraved stone (right) proclaims that Richard III’s remains lie nearby.

In addition, tales of the fevered despoliation of Richard’s tomb had unleashed a material counterpart to the royal bed for gossip and commerce – a royal coffin. Some 50 years in the ground before retrieval and a further 75 before first noted, the coffin could not be wood, and a stone one was duly found and proudly displayed at another inn.4

By 1861 the coffin had long disappeared. The old Blue Boar Inn, a fine piece of medieval architecture, had been demolished in 1836. That left the bridge as ‘the only relic reminding the historical student of Richard’s presence in Leicester’. Now that had gone, too. The town was entirely ‘without a memorial of the king whose name lives in every man’s thoughts’.5

The new Bow Bridge, completed in 1862, was cast iron; the decorated parapets, recently painted, feature red and white roses and Richard III’s coat of arms detailed in blue and gold.

Well, perhaps not quite. The construction of a new bridge gave the opportunity for some inventive new commemoration. As I approach, the first thing I see is a cast-iron plate marking the name, Bow Bridge, partly obscured by the luxurious greenery and white elderflowers of a late, very wet summer. The bridge itself – strictly there are two, for two parallel lanes – is rich in historical imagery, cast in iron, newly restored, and painted in white, red, gold and black. At the centre of each parapet is Richard III’s coat of arms, with a touch of blue. Two white boars hold up his crest, their hind legs standing on a motto – barely visible under layers of paint – that reads Loyaute me Lie, or loyalty binds me.6 Either side, in alternating panels, are red and white roses.

As the quaint medieval bridge was swept away for industrial splendour, myth was fixed in iron. ‘Upon this bridge’, reads a cast plaque, ‘stood a stone of some height, against which King Richard by chance struck his spur.’ A wise woman noticed, and predicted that as his foot hit the stone on his way out, so on his return his head, hanging limp, would do the same. Forsooth.

The story, and the style, came from John Speed’s Historie of Great Britaine, published in 1611. It was well known, if only from Speed’s telling, but for one anonymous citizen of Leicester its representation on the new bridge was a mistake, favouring ‘the puerilities and fictions of the gipsy fortune teller’ – what another writer judged rather to be a ‘historically interesting … tradition’ – over proper history.7

Yet while people argued about the relative merits of history and custom, the construction of the bridge had thrown up some solid evidence that no one was expecting. During the work, the river had been dammed so that the bed was comparatively dry. When the stone piers were taken out, wooden stakes were found, and faggots (bundles of twigs). These could have been part of the bridge’s foundations, or conceivably from an earlier bridge, perhaps even a Roman one. More curious still, workmen digging on the east side of the bed unearthed an almost perfect human skeleton, close to a stone pier; the skull of a horse and an ox horn were found nearby.8

The men must have wondered if they’d stumbled on the king. Even as they wiped the dark mud from the bones, they could have read – or if needs be, have had read to them – Broadbent’s words, looking down on the dry river bed: ‘Near this spot lie the remains of Richard III’. The story spread quickly. King Dick had been found.

Meanwhile, the remains were bundled into a basket and carried off for examination. A local surgeon announced the skeleton to be that of a 20-year-old male (thus too young to be Richard III) of lower than average height. The skull was shown to a passing phrenologist – apparently the sort of visitor to be taken for granted at that time – who said it revealed a man of ‘inferior intellectual development, who possessed some constructive skill, with large animal propensities’, or, in plain English, an idiotic builder.

The phrenologist thought the stupid man had thrown himself into the river less than a century before. Another observer objected that the skeleton was truly ancient – not just medieval, but prehistoric, perhaps not even a modern human, and thus of immense value to science (Darwin’s On the Origin of Species had been published less than three years before).9

The bones are now lost, so we cannot examine them ourselves. Lone skulls were also said to have been taken from the river, and sometimes attributed to Richard III; most of these too are lost. The completeness of the skeleton suggests a grave, and the best guess is that it was medieval. Close by, on the east side of the River Soar, there had been a friary, one of four in medieval Leicester.10 Like the friary where, according to history, Richard had been buried, at least for the first time, this one – an Augustinian foundation known as the Austin Friars – had been demolished at the Dissolution in the 16th century. But beneath the ground, wall trenches and drains still survived, as did rubbish pits and cellars, and hundreds of graves. As the braided River Soar eroded its banks, it had probably undermined some of these burials.11

A century later, archaeologists were alert to the promise of this old friary site. It was in a triangle formed by two channels of the Soar, north of the road between Bow Bridge and West Bridge – the point where King Richards Road, crossing the river into Leicester, becomes St Augustine Road, the friars’ road. It had never been a fashionable part of town, outside the walls, low-lying and wet. It was a place of factories, and one of the country’s earliest railway terminuses – built to move coal, not people. After the Soar had been cut into a canal in 1889, drainage improved and new housing spread rapidly – this was when Tudor Road was laid out, with branch streets named Bosworth, Tewkesbury, Warwick and Vernon. But no houses were raised over the old friary.

By the 1960s, the railway had closed, the factories were running out of steam and developers were eyeing the land. It was the opportunity archaeologists had wanted. They knew there were remains of great potential interest, remains that would be destroyed if new works occurred. The threat released funds from central government, and in 1973 an excavation began, looking for the Austin Friars.

And down there, among the roads named after battles, dynasties and kings, where Richard III had marched out to Bosworth and where Henry VII had entered Leicester, where myth blended with record to create a unique memorial to momentous events and unforgettable men, came a schoolboy on his first-ever dig.

His name was Richard Buckley.

Half an hour’s walk across town is a proper memorial. Built in the 1920s and designed by Edwin Lutyens, it is a beautiful and elegantly austere, monumental arch faced with pale Portland stone. Inspired by ancient Roman architecture and mythology, it bestrides the axis of the rising sun on Armistice Day, honouring the 12,000 Leicestershire men who died in the First World War.12

It is near this arch, among a group of buildings on Peace Way, that Richard Buckley today has his office – the land for the University of Leicester was a gift, another memorial to the dead of that great war. The university’s School of Archaeology and Ancient History is one of the country’s largest and most popular departments of its kind. It is home to the independent University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS), a group of professional field archaeologists who work across the UK, turning over three quarters of a million pounds a year – over a million US dollars – in contracts to businesses and public agencies, from one-man builders to supermarket chains, airports and the BBC. ULAS has two directors: Patrick Clay and Richard Buckley.

If not on its present scale, nor by these institutions, archaeology was taught and practised in Leicester when Richard Buckley was at school. His first experience of digging, where he learned to use his first trowel, was with the predecessor of the organization he now co-directs, the Leicestershire Archaeological Unit. As we sit and talk in the university office, there’s little around us – apart from the scuffed black computers – that would have been out of place in the 1970s: tightly packed tables, piles of typed reports, bags and boxes on every surface, posters on the walls and dirt on the floor. A striped black and yellow parking ticket stuck to a desk, and Richard’s well-used coffee mug bearing a portrait of Richard III, remind me why I’m here. But though the way digs are now run has changed radically – more professional, concerned with clients as well as finding things – inside this office, discussing a schoolboy’s first brush with archaeology, I am transported back to another age.

It began when he was just six or seven, forcing his parents to visit castles, and collecting coins. They’d go to the Tower of London, and he’d notice the money in his mum’s purse included Victorian pennies. He...