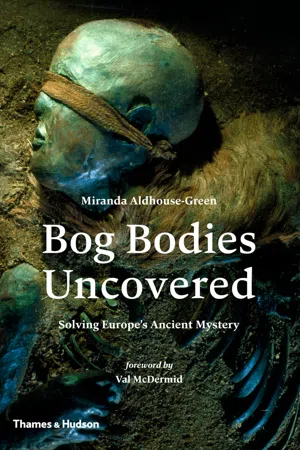

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Discoveries & Discoverers

The axe-men came on an ancient and sacred grove. Its interlacing branches enclosed a cool central space into which the sun never shone, but where an abundance of water spouted from dark springs

LUCAN, PHARSALIA III, 399–4001

Even today, the exact spot where, in the early 5th century BC, the middle-aged Haraldskaer Woman was strangled and fastened down beneath the cold dark water is a remote and desolate place. This is particularly so in the sombre Nordic winter months, when the sun struggles to light the sky and the surface of the water gleams icy and grey even at midday. Small trees flank the bog and a tangle of vegetation litters its surface. The watery grave of this woman is full of atmosphere, and the horror of her death and immersion still seems to cling to the place, as though an unquiet spirit continues to have a restless presence.

A lonely 19th-century peat cutter, digging up turves and unearthing a well-preserved but leathery body, might easily have thought it was a bog sprite whose dwelling place he had inadvertently disturbed. Today’s peat harvesters use huge mechanical diggers rather than spades but, even so, to come across a human body lying in the peat is not something to forget in a hurry. The same feeling of shock and disbelief is experienced. But the modern industrial methods used in cutting peat mean that ancient bog bodies are more likely to sustain catastrophic damage, and body parts may be dragged for considerable distances by the machinery before they are recognized for what they are. So, although our knowledge of bog bodies is vastly superior now compared with that of more than a hundred years ago, paradoxically those early discoveries are often more complete than the bodies that still turn up in the peat.

Early 20th-century peat cutters, working with traditional horizontal-bladed spades, in southeast Drenthe, Netherlands.

‘MAIDENS OF THE MIST’: EARLY PEAT CUTTERS AND THEIR FINDS

The 16th century saw the first major exploitation of bogs. Marshes were drained by digging channels through them, and the peat harvested and cut into turves, to be taken to cities and sold for fuel. Driven by the increasing demand for peat-fuel, new settlements grew up amidst the bogs and a new profession, that of the peat cutter, was born.2

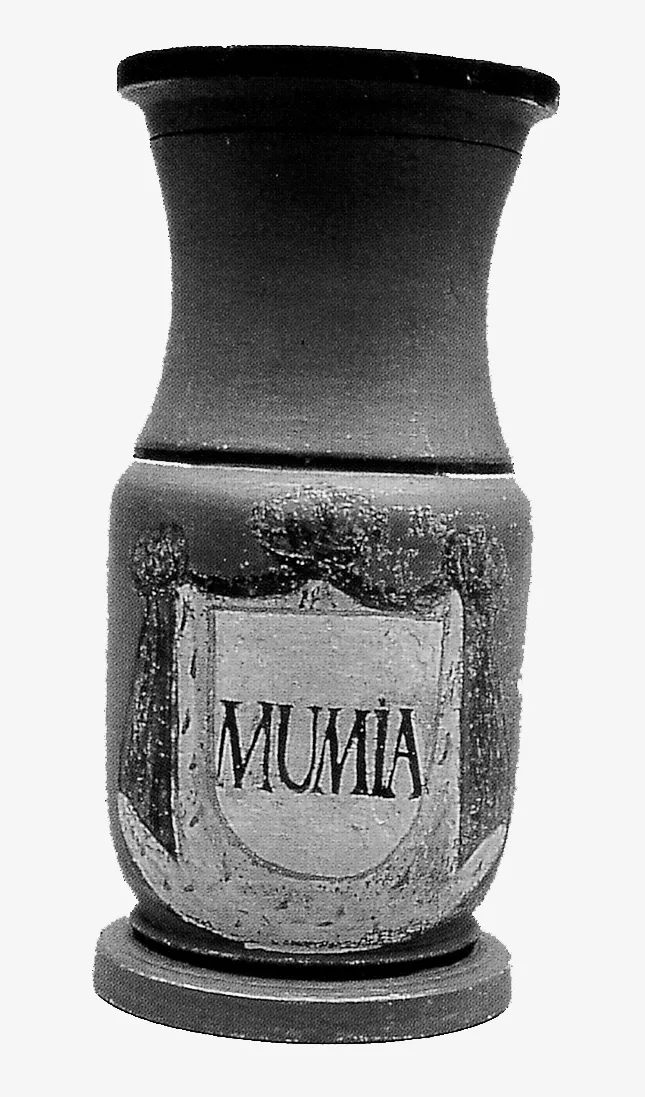

An 18th-century pharmacist’s ‘mummy pot’, from the Netherlands, used to store ground-up bog body parts for medicinal purposes. Dutch people still ingested these powders until the early 20th century.

It was a 17th-century Dutch clergyman, the Reverend Picardt, who coined the phrase ‘maidens of the mist’ to describe the mythical creatures presumed – by the people of Drenthe in the Netherlands – to inhabit the ancient burial mounds in the vicinity of raised bogs. The notion that bog spirits could emerge from the vapours lying on the surface of peat bogs is as old as the tradition of bog drainage for cultivation and peat cutting for fuel. The presence of human remains in European bogs was noted at least as early as the mid-17th century, along with clothing, leather, coins and jewelry. Most of these early human finds were discarded but some were ground up into a powder, put into jars labelled ‘MUMIA (Mummy)’ and sold as a medicine.3 By the middle of the 19th century, people with civic authority were becoming aware of a need to conserve the past, and the growth of town and city museums provided a focus for the storage and display of ancestral relics. Museums offered to pay for finds and so peat cutters began to look for ancient objects to augment their meagre income. Of course, when human bodies were found, they were immediately suspected of being the victims of contemporary crime and were the subject of police investigations. But usually the bog bodies were eventually dismissed as those of poor travellers who had wandered off the paths and drowned in the treacherous marshes.

FINDING THE YDE GIRL

Last Wednesday, men working for Mr. L. Popken in Yde discovered a complete human skeleton in a boggy area between Vries and Yde. The hair, which was over 18 inches long, still covered the skull. There were also some remains of clothing. Since things decay very slowly or not at all in bogs, the corpse could have been lying there for at least a dozen years.

FROM A DRENTHE NEWSPAPER ARTICLE, MAY 18974

On a balmy day in May 1897, two peat cutters were working just outside the village of Yde in Drenthe, when they came across something that chilled their blood. Uttering the curse ‘I hope the Devil gets the guy that dug this hole’, they flung their spades aside and ran away to their homes, scared to death. Tongue-tied with fright at first, they gradually recovered sufficiently to tell what they had seen, and the local newspaper carried the story of the bog body the two workers had found. It was a strange sight: the mummified remains had been placed in the bog wearing a long robe, half the long hair torn out, the neck still bearing the strip of fabric that had strangled the victim, wound tightly round the throat. The remains were taken to the Provincial Museum of History and Antiquities at Assen. The mayor and the museum committee realized that the body was valuable and, based on its location deep in the uncharted bog, they considered that it must be at least 600 years old, and almost certainly that of a female. The only sceptic was the museum’s president, who was convinced that it was not a human being but an ape!

Dating the body was a problem. In 1955, the original estimate of 600 years was revised: peat fragments adhering to the feet contained pollen, and its analysis showed the body to be far more ancient. A date of between AD 200 and 500 was estimated. The remains were redated in 1988, using the radiocarbon method, and the date of death now accepted is between 54 BC and AD 128. Recent scientific tests indicate that the body was indeed female, but she was a teenager, 16 years old at most, and was buried wearing a threadbare woollen coat that might suggest low status in life. The Yde Girl is one of very few ancient bog bodies to have been interred fully clothed. As well as the garrotte that finally killed her, she was found to have sustained a knife wound close to her collarbone. Her life was not only short but painful and difficult, for she had acute curvature of the spine, which would have severely compromised both her growth and her mobility.5 A sad end to a sad life, but perhaps her long coat demonstrated that someone cared enough about her to ensure that she kept warm in her final hours. In his poem Punishment, about a fellow bog victim, the adolescent from Windeby in Germany, Seamus Heaney affectionately refers to a ‘little adulteress’, citing sexual misconduct as a reason for the killing. That is a possible reason for the Yde Girl’s fate, but – as argued later – her strangulation and immersion may have been more complicated than that.

The body of a teenage girl, strangled and knifed in the 1st century AD, and found in a peat bog at Yde in the Netherlands in 1897.

GRAUBALLE, TOLLUND AND ELLING: THREE DANISH BODIES UNCOVERED

He was a handsome and stately figure and is very heavily built and any presumptions of a certain crudeness in our Germanic ancestors in the Iron Age is upset by the fact that he has beautiful hands and almond-shaped nails.6

It was just an ordinary morning in Tage Busk Sørensen’s daily life, in April 1952. He had set out as usual with fellow Danish workers to cut peat in the Nebelgaard Mose. But his life was changed forever when his spade struck something odd, softer than the branches of bog oak he was accustomed to encounter during his work. Tage had found Grauballe Man. Like something out of a children’s story, the village postman arrived, he told the local doctor, who in turn contacted Professor P.V. Glob of the Museum of Prehistory at Århus.7 Glob’s primary and immediate concerns were the preservation of the body once it had been extracted from the protecting bog, and its context and chronology. Detailed analyses of the stratigraphy, the associated pollen and the body itself revealed that the Grauballe body, that of an adult man, died in the early Iron Age (from having his throat cut from ear to ear), and that he had been stripped naked then deliberately placed in an ancient flooded peat cutting (PL. V). In 1952, the liver was taken from the body for radiocarbon dating, a technique then in its infancy. The initial analysis was carried out four years later, giving a date between the 1st and 5th centuries AD. Problems arose because of the plant tissue that had grown up through the body, meaning that it was difficult to determine what was actually being dated. After many subsequent attempts to refine the chronology, in 2002 came the most accurate date: Grauballe Man died in the early Iron Age, perhaps as early as 390 BC.8

The ethical debate that surrounded the find gives an interesting insight into 1950s Denmark. There was a sensitivity about the public display of human remains that is less evident today. This being so, cosmetic considerations came to the forefront, and it was deemed particularly important that the ancient body should look as good as possible before he met his public. Furthermore, permission had to be granted by the local bishop before Grauballe Man could be seen outside the scientific community. Huge interest surrounded his discovery and subsequent display in the museum and 18,000 people visited the 10-day exhibition. After it was over, it was time to address the urgent issue of preservation. The story of this battle to keep Grauballe Man from turning to dust from exposure to the air is told in Chapters 3 and 4.

The face of Tollund Man, killed by hanging in the 4th century BC. After his death, he was placed carefully in a Danish peat bog, naked but for a cap and belt.

The circumstances surrounding the discovery of the body from Tollund, f...