![]()

1

Searching for the American Dream

I never thought I could come Into McDonald's, .McDonald's is a big foreign corporation. My friend told me if I want to leant English you can try this. We are all from China hut [speak] different languages. I speak Mandarin. They speak Cantonese. So we are always commimicatingwith English,

—Tina, a fast food worker from Shanghai working in Chinatown

Tina, who is from Shanghai, never expected to work in a fast food restaurant when she arrived in the United States at the age of twenty-four. In Shanghai, Tina was a television repair technician and had no reason to believe that she would change her job; compared to her parents' factory jobs, hers was a good one. Tina had never expected to leave Shanghai until her parents arranged for her to meet Paul, a prospective husband. Paul had moved to New York in 1984, where he had been working, but now lie was back in Shanghai to find a wife. After meeting Paul, Tina readily agreed to the arrangement, and they married right away.. When Paul returned to New York, Tina stayed behind, spending the next two and a half years waiting for her immigration papers and wondering what life in the United States would be like.

Tina harbored few illusions about streets paved with gold or of life in a luxury suite on Park Avenue; she was too sensible to be taken in by media hype. Her husband was not a Wall Street investment banker. He did not even speak English. Rather, he was one among tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants living and working in the satellite Chinatowns of New York's outer boroughs. These immigrants usually live in arduous conditions and work for less than the minimum wage. The New York Daily News reported in 1995 that Chinese workers in New York's Chinatown are likely to work in slave-like conditions: grueling hours for pitiful wages and no benefits.1 Paul worked as a chef in a Chinese restaurant owned and staffed by Chinese immigrants. With a brutal schedule of twelve to sixteen hours a day, six days a week, and compensation at far below the minimum wage, he had no time, energy, or resources to pursue another job, or even to take English-language classes.

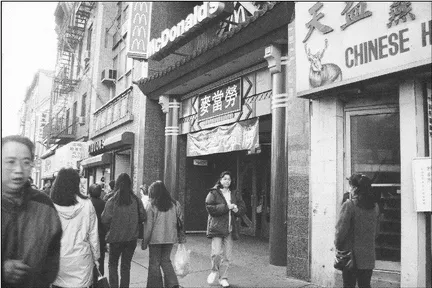

Although Tina knew she would need to work in New York, she did not anticipate taking a job in a McDonald's restaurant. American fast food was not completely unfamiliar to Tina; after all, there was a Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) restaurant in Shanghai. But she had never considered working there because only the "poor" or "jobless" accepted such work. Once she had arrived in New York, however, Paul encouraged her to get out of what he called the "Chinese environment" and venture into the "foreign environment." The "Chinese environment," according to Paul, is the Chinese ethnic enclave in the United States consisting of Chinese-owned restaurants and garment factories that typically employ people off the books. The "foreign environment," by contrast, refers to mainstream and legal sectors outside the Chinese enclaves, such as McDonalds and KFC, that are usually thought of as "American" institutions. It is interesting that Paul and Tina view McDonald's as foreign when the general public has long viewed Chinatown as foreign. Paul thought that in the so-called American environment Tina could learn English and gain mainstream skills; a guaranteed paycheck; safer working conditions; and important benefits, including health insurance.

An acquaintance, also from Shanghai, told Tina about a job opening in a McDonald's in New York's largest and oldest Chinatown, which is in lower Manhattan. This acquaintance was working at the restaurant and encouraged Tina to apply. She said that McDonald's was a big company and that the job would help Tina learn English and possibly give her an opportunity to move into management. If she reached the upper-level management ranks she could earn an annual salary of more than $15,000 and receive health benefits for her family Because Tina wanted to start a family, she placed great hope in these prospects; she expressed particular concern about her husbands health and the need to have health insurance when having a baby:

So many of the places [in the ethnic enclave] don't have benefits. Just now you ask nn- the most important thing and I say the benefits is very important. It is very useful for the whole family. When a newborn baby go to the maternity ward ... I want to get benefits. My husband now does not have any benefits. Two months ago he was sick. The doctor told us he needs to operate. Now he has no benefits. He is applying for Medicaid. But I know it is very hard to apply because so many people apply for it. I told him now I want to have a job that covers the whole family the benefits.

She also expressed the importance of providing a stable home for her children so that their education and future mobility would be secure. This goal included knowing the English language.

It is very hard for my whole family when we have a baby and it grows up and goes to the school to speak English with other children [if the parents do not speak English], When he or she goes home they maybe cannot communicate with the parent and we want to take care of that. . . . He [my husband] doesn't understand English, that is why he asked me: to study and learn English.

Tina traveled one-and-a-half-hours (each way) by subway from her home in Flushing, Queens, to Chinatown in lower Manhattan to apply lor the job at McDonalds, She was hired immediately by a Taiwanese general manager, despite her lack of fluency in English. Her only option, she said, was to join the thousands of other Chinese women working as sewing machine operators in Chinatowns garment factories.

Tina would seem to defy stereotypes of the typical McDonalds employee: an American-born high school student working for pocket change after school on his or her way to college, or at least to a better job. But thousands of new immigrants are finding jobs in the city's American fast: food restaurants, and these workers now make up the majority of New York City's fast food employees. Whereas many immigrants, such as Tinas husband, continue to rely on traditional immigrant work sectors and niches in "ethnic" restaurants and factories or as maids and nannies in upper-middle-class homes, others are joining the mainstream consumer world: They serve cappuccino, take movie tickets, and flip burgers.

Since the new immigration policy began in 1965, the proportion of foreign-born residents in the United States has tripled, reaching its highest point in seventy years. New immigration policy changed restrictions on the national origins of immigrants; this means that people from all over the world, including millions of Third World immigrants who had been previously excluded, can now live and work in the United States.2 Today, one in ten Americans are foreign-born.3 Immigrants come to New York, one of the largest immigrant-receiving cities ill the United States, from countries all over the world; they find homes and jobs in immigrant neighborhoods from Little Odessa, 011 the far reaches of South Brooklyn, to Little India in Queens and Little Dominican Republic on the northern tip of Manhattan.

It makes sense for these new immigrants to seek jobs at fast food restaurants; they are one of the fastest expanding industries in the low-wage economy, and immigrants have always filled bottom-rung jobs in the United States. Thousands of fast food franchise restaurants have sprouted throughout the city: in business districts, at tourist attractions, and in old and new immigrant neighborhoods. They provide a quick bite to eat for employees on their lunch breaks and for sightseers heading to the Statue of Liberty or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But in the immigrant neighborhood, these restaurants are places where new immigrants find work, invest in ownership, and introduce their children to a piece of American culture and cuisine.

Fast Food Restaurants and Immigrant Neighborhoods

Immigrant neighborhoods having strong cash flows and a workforce eager to "Americanize" are ideal targets for the fast food industry. The industry's expansion into the immigrant neighborhood supports a common notion that fast food restaurants contribute to the homogenization of culture around the world. In his book The McDonaldization of Society, George Ritzer pessimistically envisioned a "McDonaldized" world culture in which Western-type corporate institutions devoured local cultures and institutions. To some extent, the fast food restaurant in the immigrant neighborhood does indeed upset local cultural tradition.4

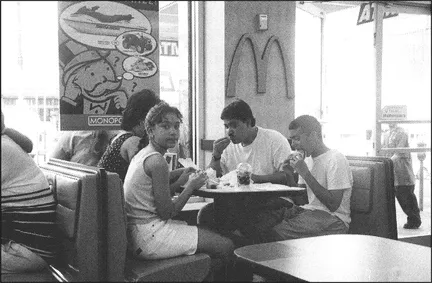

PHOTOGRAPH 1.1 A Dominican Family at McDonald's. (Photo courtesy of Samantha Rosemellia, reprinted with permission)

A young family from the Dominican Republic, for example, may visit a McDonald's to celebrate a child's birthday rather than going to a public park for a cookout with their neighbors (see Photograph 1.1). Or, while their young children play at a safe indoor playground, parents are more likely to chat and sip "American" coffee from Colombia than to drink café con leche at a nearby Dominican restaurant. Or Chinese children, influenced by television commercials or their most recent school outing to a McDonald's, talk their parents into taking them to the local restaurant where they munch on Happy Meals while the parents drink tea.

It is surprising that contemporary studies of ethnic neighborhoods in the American city, particularly those that focus on immigrants' jobs and entrepreneurial efforts, have steered us into thinking almost exclusively about immigrants' segregation and isolation from mainstream society.5 Consequently, we know a great deal about immigrants and the labor market in "ethnic economies"—where employers and employees share the same or similar ethnicity, and in "ethnic enclaves"—where ethnic economies are geographically concentrated in immigrant neighbor-hoods.6 But we know surprisingly little about how immigrants fare in mainstream businesses, such as fast food, which often flourish in the same neighborhoods as ethnic enterprises.

Immigrant neighborhoods such as Chinatown and Little Italy have long helped us understand how immigrants adapt to working in the United States; these neighborhoods give immigrants an initial foothold in American society their first step toward making the United States home. The immigrant neighborhood has been conceptualized as a geographically concentrated area where immigrants preserve their cultural traditions—language, religious customs, and family practices—from the old country. In Flushings Chinatown, for instance, Tina and Paul live among other Chinese immigrants, attend religious services held in their native language, and shop for the Chinese spices and rice noodles that are not ordinarily found in mainstream grocery stores.

The cultural needs of the immigrant community often depend on small businesses and entrepreneurial enterprises that create jobs for immigrants. Chinese restaurants, food markets, and garment factories in New York's Chinatowns and Latino-run garment factories in New York's Little Dominican Republic are good examples; here, many immigrants, particularly those least qualified for good mainstream jobs, find work and entrepreneurial opportunity through neighborhood and ethnic networks. Jobs in the mainstream or general economy are largely unavailable to many of these immigrants because they lack legal work status, mainstream skills, social connections, fluency in English, and education.7 But living and working in the same neighborhood is also convenient. The Chinese restaurant where Paul works, for instance, is a few minutes' walk from where they live. Meanwhile, Paul and others like him provide a stable and continuous source of employees for Chinese restaurant owners.8

Now we must wonder why and how immigrants are turning to fast food restaurants in these same neighborhoods. Is the industry drawing on the same people who work in these traditional ethnic sectors? Or is it drawing on different groups altogether? Are immigrants carving out an occupational niche in American fast food restaurants, an industry long perceived as the quintessential employer of American teenagers? Are immigrants using jobs that the American public considers dead-end and last resort as a stepping-stone into the American mainstream Culture and economy? Do fast food restaurants in the immigrant neighborhood provide the same opportunities as traditional ethnic enterprises or different ones? Or are fast food jobs in the immigrant neighborhood simply dead-end opportunities that reflect the already polarizing forces of the American city and the economy at large? And in the long run. does the fast food restaurant help reinforce or break down the ethnic community in the immigrant neighborhood?

Corporate Capital and Ethnic Enterprise: New Partners in the Global Economy?

Answering these questions requires us to move beyond the "McDonaldization of Society" argument as well as the image of immigrant communities as homogenous and immigrants as socially isolated. James Watson, in his work on the global expansion of American-style fast food restaurants in East Asia, argues that the spread of global cultural institutions is not a unilateral process, as George Ritzer believes; nor are immigrant communities immune from these processes, as the ethnic enclave literature would suggest. Rather, it is a two-way street and it operates through "multilocalism." Local peoples and the state play significant roles in shaping the way global institutions such as McDonald's operate, including the social uses and meanings associated with them.9

American fast food restaurants, and the corporate capital they represent, are woven into the local dynamics of the American city. Their foray into ethnic communities complicates the immigrant neighborhood's role in helping immigrants adapt to American society, more so than the etlnic-economies theory accounts for. They also complicate the "McDonaldization" thesis by allowing local actors to shape corporate-level processes. This new linking of the global with the local in ethnic neighborhoods is what this book is about.

On the one hand, fast food restaurants are similar to the traditional ethnic eatery. They are small and labor intensive, and they offer low-wage, non-union,, and contingent jobs. They operate in immigrant neighborhoods and they target ethnic groups. Often, immigrants own them. Fast food restaurants hire cultural managers (who represent the neighborhood) and rely on ethnic networks to steer immigrant workers into the establishment. On the other hand, their links to giant corporate structures, what economists term primary firms, complicate the way they operate. This book examines these links and how they affect immigrant workers.

Unlike the independent immigrant restaurant, fast food restaurants are connected to outside organizations and hierarchies; these, in turn, link local restaurants to corporate headquarters. Although more immigrants are buying fast food restaurants, those still owned by large New York-based corporations enjoy large capital reserves. Because they are part of giant global corporations, their operations employ the economies of scale, advanced technologies, and global corporate marketing campaigns that provide advantages only dreamed of by independent immigrant owners.10 In addition, trends in the corporate consumer economy at large demand that work processes emphasize image, personality, and flexibility.

Arlie Hochschild, in a study of flight attendants, identified a particular kind of service worker in modern corporate society—the "public contact" worker—whose main job is to interact with customers, perform "emotional labor," and comply with standards set by corporate-defined and publicly propagated criteria.11 Immigrants, by selling their "smiles" behind the fast food counter, are the go-betweens linking impersonal mass institutions and new immigrant communities in the corporate quest for new ethnic markets. But as Robin Leidner points out, fast food work is tempoi'ary and contingent, and workers are unlikely to identify with their jobs and the companies they work for.12 Is it any different among immigrants in the ethnic neighborhood?

Negotiating Work—American-Style

The varied experiences of immigrants as they bridge the mainstream and ethnic cultures of immigrant neighborhoods reflect the complexity of new workplace: arrangements. As Tina suggests at the beginning of this chapter, the fast food restaurant is a place where she, from Shanghai, can learn to speak English, become accustomed to mainstream workplace customs, and build what sociologists call social capital, or what the mainstream refers to as networking: developing relationships with people who are able to guide one to better opportunities. All this happens while Tina works alongside people having similar cultural origins and in a neighborhood that, in many respects, reflects her cultural past.