Soft Skills for the New Journalist

Cultivating the Inner Resources You Need to Succeed

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Soft Skills for the New Journalist

Cultivating the Inner Resources You Need to Succeed

About this book

Journalism is a pool staffed by distracted lifeguards and no matter how fancy your school is, your first week in a real newsroom will feel like a shove in the small of the back into 15 feet of water. Most of us come up for air eventually, but if you're like journalist and educator Colleen Steffen, you may still be left feeling like all that training in inverted pyramids and question lists left something important out: you!

Journalism is people managing, wrestling truth and story out of the messy, confusing raw material that is a human being, and the messiest human involved can often be the reporter themselves. So it's time to talk about it. Instead of nervously skirting the sizable EQ (emotional intelligence) portion of this IQ (intelligence intelligence) enterprise, Soft Skills for the New Journalist explores how it FEELS to do this strange, hard, amazing job—and how to use those feelings to better your work and yourself.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

A is for Attitude

- Not knowing something but not asking for more info, then messing up or taking eight times longer than necessary.

- Getting in over their head on a topic, and not asking for help, deadlines blowing by in the rearview mirror and mistakes obvious to any local riddling their copy.

- Trying to take up too much space, talking too definitively on too many topics and bragging too much on not enough accomplishments, with resulting general hatred.

- Pitching a fit when they don’t get handed the big story, the plum assignment, the premier space.

- Pitching a fit whenever an editor changes their copy, or as one of my beloved journalism profs used to put it, murders their darlings.

Another way your attitude sucks

Who do you think you are???

- When someone catches you in an error, admit it without making an excuse. Apologize and offer some changes you’ll embrace to avoid making the mistake again. Watch their anger and/or the angry speech they were about to make deflate like a popped balloon.

- When someone does something you like, tell them. Great story? Tell them. Awesome idea? Tell them. This is rare currency in competitive newsrooms. (Be genuine—we’re professional BS detectors.)

- Remember, there are no boring stories, only boring reporters. Don’t use a perceived lack in the assignment, the sources, the editing to excuse your poor performance, your less-than-overwhelming effort. A great reporter could work around these things, don’t you think? Go be greater.

- P.S. I find the open admission of not knowing or not understanding something works its magic in non-newsroom settings as well. Try it out in your next class, for example—raise your hand and ask your professor to clarify a topic. Watch their little face light up with joy that someone actually cares. Or next gathering you’re at, ask someone you don’t know well to explain their obscure job to you. Actually try to listen and understand. I might have just handed you the key to human love right there.

Note

Chapter 2

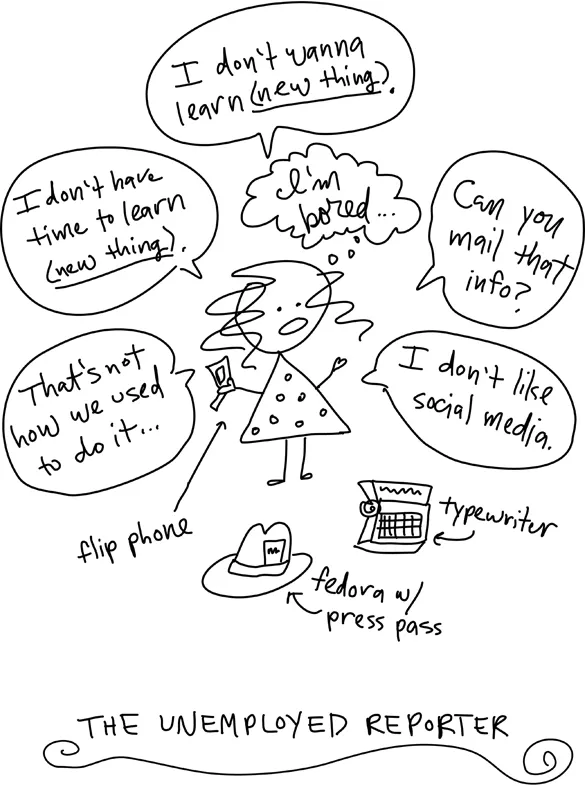

I went to college with an electric typewriter, and other cautionary tales

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Welcome and congratulations! You’ve chosen well

- 1 A is for Attitude

- 2 I went to college with an electric typewriter, and other cautionary tales

- 3 Finally we get to the important stuff

- 4 So something shiny caught your eye …

- 5 Working on your pitch (not the sports kind, sorry)

- 6 Editors have the worst ideas

- 7 Hi, stranger! The in-person approach

- 8 Can’t I just email???

- 9 The shy person’s guide to not dying inside while on assignments

- 10 Not everyone is going to like you (unreasonable but true)

- 11 All about sources

- 12 Take a flying (imaginative) leap

- 13 The all-important nutgraf

- 14 So … I’m supposed to say what to this person?

- 15 OK! Finally! Interviewing!

- 16 Journalism magic—it’s a thing!

- 17 Or maybe just shut up for a minute

- 18 Don’t rush off to lunch just yet

- 19 Yes, you still need a notebook

- 20 Don’t be a banker

- 21 Get in shape

- 22 To outline or not to outline

- 23 “I hate writing; I love having written.”—Dorothy Parker

- 24 But also … try this to love writing a little more

- 25 Get your crap together

- 26 How to tell when you’re done

- 27 A word about grammar

- 28 Developing a journalist’s conscience

- 29 The day after

- 30 Speaking of what other people think …

- 31 You did it! You’re done!

- 32 WWNBD? (What would Nellie Bly do?)

- 33 Keep your head in the game

- 34 I believe in you! Goodbye!

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app